When Darlyne Bautista was growing up in Winnipeg as a budding Filipino-Canadian author, she felt lucky to be a “majority of a minority.” Born and raised in the north-end of Winnipeg, a historically large settlement for immigrants, Bautista strongly felt the presence of community despite being a minority in Canada.

“When I speak to other Winnipeggers who are from different parts of Winnipeg, I’m very grateful to have to [gone] to a school where a lot of children have different coloured skin,” Bautista said. “Some children who grew up in more affluent areas talk about…being the only brown child in a school and I’m very fortunate that I’ve never experienced that.”

But one thing Bautista did miss was access to a Filipino language program—one that not only opens up opportunities for students to learn Filipino, but to also see themselves represented in the materials they study.

This year, Manitoba’s largest school board—the Winnipeg School Division, which oversees the education of 30,000 students—is planning to introduce exactly this type of program. It’s the second program of its kind in Winnipeg. Bautista helped advocate for the launch of the province’s first ever Filipino bilingual program introduced in 2018 at Seven Oaks School Division, a smaller school district in Winnipeg.

“Heritage language program[s] will give children that sense of confidence of self in their identity formation as a minoritized child,” Bautista said. “I wish I had that as a child because my adolescence was so bumpy but I feel hopeful, and I see the children in that program and just tear up because you don’t know how many people before me were fighting for that. I’m grateful that I was there to see it.”

Winnipeg is home to some 80,000 people who self-identify as having Filipino ancestry, according to 2021 Statistics Canada data. One in four Canadians in 2021 (or nine million people) had a mother tongue other than English or French.

The rise in Canada’s linguistic diversity, advocates say, is reason enough for more bilingual programs like WSD and Seven Oaks’ that reflect the diversity of Canada’s children.

Bautista played her own role in this fight for representation through her advocacy work and by publishing her children’s book, Where is Winnipeg?, in 2011. This book explores what immigration can feel like for a child, with readers following the main character as she asks her family and community, “Where is Winnipeg?”

Exploring immigration through a child’s eyes

Bautista’s parents moved to Canada after they were recruited under a provincial garment industry recruitment scheme that ran in the late 1960s to mid-70s. Their family, as described in a paper co-authored by Bautista, were among the first Filipino immigrants who moved to Canada after being recruited due to the country’s labour needs.

They moved to Winnipeg in the 1970s from the municipality of Angono, Rizal in the Philippines. Growing up in Winnipeg, Bautista describes the long history of the diverse and connected community she grew up with.

“We all had a kind of empathy and understanding with one another,” Bautista said. “Some of our fathers all worked in the same factories and after the garment [businesses] started shutting down in the 80s, we could see our mothers talking about where to apply next or who’s gonna babysit whose kid — it was very much a community that I still long for.”

Bautista’s connection to her community is what kept her in the loop of what immigrant children experienced. Aside from her work as an author, she is also a community activist and co-founder of the organization Aksyon Ng Ating Kabataan (ANAK) — meaning “Action from our youth” in Tagalog. ANAK provides resources, education, and mentorship with the aim of preserving Filipino-Canadian culture and heritage.

Through ANAK, Bautista worked with recently arrived immigrants and saw the process children went through as they adjusted to their new home. She also noted the differences between Filipino immigrant children and Canadian-born Filipino kids.

“When you see two generations of children of the same age…one just arrived and one born in Canada, people don’t understand that even though those two children may look alike or they are the same age, that…generationally as Canadians they’re very different,” Bautista said. “That doesn’t necessarily mean that those two children will understand each other. I wanted to create a baseline of understanding for all children, for whoever’s reading that book, whether they’re Filipino or not.”

Although the focus of the book may be on the child’s perspective and their burning questions about where they’re going, Where is Winnipeg? also tells another side of the story: the idealistic and fantasy view of immigrating.

Bautista touched on how families in the Philippines often have preconceived notions of what Canada is like, and explores this concept in her book—often through characters inspired by her own family.

“They imagine that because I’m from abroad, that I’m a different person, and that colonial mentality [that] everything is better elsewhere, and here I am longing to learn who I am in the Philippines,” Bautista said.

“So I put that commentary among all of the different characters. Some of them are my relatives! I do have bitter relatives, I do have jolly relatives, I do have curious relatives, I do have know-it-all relatives… I think we all have relatives like that. I try to play on both sides.”

Tribute to family

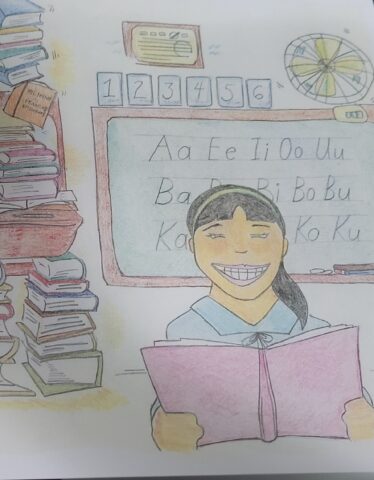

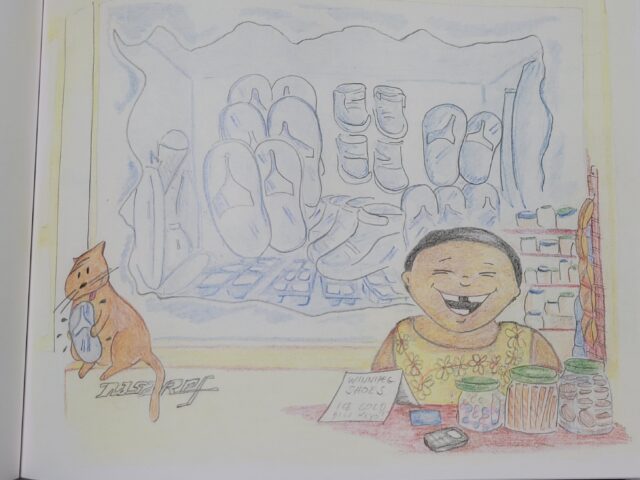

Throughout the book, Bautista’s illustrations feature nods to everyday life in the Philippines.

One page features a sari sari store—a small neighbourhood store selling a variety of goods— and another features a tricycle—a common mode of transportation. The illustrations of the characters are based on her own family, and though representation is important, it wasn’t Bautista’s primary focus when she set out to write the book.

“The Tita Mameng in the sari sari store with no teeth, that’s my Tita (Tagalog word meaning ‘aunt’)… Miss Husay is my cousin, not a teacher, but she is one smart go-getter that’s always smiling, and so I put her in there,” said Bautista. “I didn’t think about representation when I was writing it, really. It was more a tribute to my family and the sense of separation.”

For Bautista, representation doesn’t mean just clichés or surface level gestures, like enjoying Filipino food — it should also be present in everyday life, like a children’s book.

This story was written as part of a partnership with Winnipeg Free Press.

This article was updated at 5pm on March 13 to clarify that the first Filipino bilingual program in Winnipeg schools was offered by Seven Oaks School Division in 2018, a smaller school district in which Bautista advocated for its addition.

Rhea Lisondra is a Carleton Journalism and Humanities graduate and is based in Trenton, Ontario. She reports for New Canadian Media and is a co-host on the podcast AZN Connection.