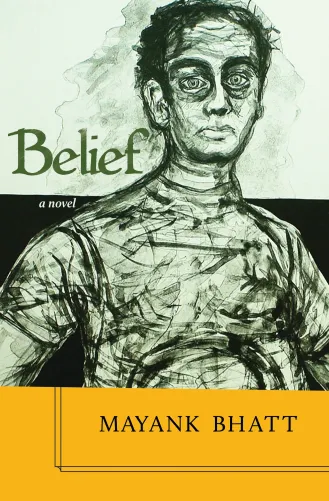

I published my debut novel, Belief, in Canada last year. It’s the story of an immigrant family’s struggle to integrate into the Canadian mainstream.

Just when everything seems to be falling into place after nearly two decades of struggle to survive in an alien land, facing constant rejection, the family discovers their son’s apparent involvement in some sort of terrorist plot. Hurriedly, they consult their neighbours, who put them in touch with a police officer known to them.

The novel explores the family’s trauma following the son’s arrest.

The family’s Muslim identity is central to the story. It deals with the manner in which people of colour who are adherents of Islam are generally (and often unconsciously) treated in a society that they adopt as immigrants.

This is an important issue because in their desperation to grab eyeballs, the mainstream news and entertainment media often forget to make it clear that Islam is not a monolith and all Muslims are not the same.

In writing my novel, I set out with a simple objective – that there is little to distinguish between people on the basis of their beliefs.

Parental dilemma

The other issue that I wanted to examine was this whole business of radicalisation and terrorism. It’s important to underline that such a phenomenon doesn’t occur in a vacuum. Young men such as Rafiq, the main character in my novel, go astray in an environment where they are unable to make an emotional or a material connection with society at large, and this leads to many complications for them, for their families and the society.

From the family’s perspective, how different would a son’s radicalisation and subsequent involvement in terrorism be from drug addiction?

I’m not saying that there is no distinction. Society will definitely distinguish between the two, and weigh down heavily on radicalisation and terrorism while condoning drug addiction, and we can argue that this has a lot to do with race, but that really is a different debate.

I’d still want to believe that it would still represent an enormous crisis from the parents’ point of view. I don’t know whether the parents of a son who’s a drug addict would take comfort from the fact that their son is “only” dealing with a drug problem, rather than being radicalised as a terrorist.

Being Muslim

The other challenge I dealt with while writing the novel was that I’m not a Muslim. This is a sensitive matter. Would I be able to portray with accuracy and empathy the life of a Muslim family, the family dynamics, and the inner turmoil?

I was born in a Hindu family. However, but for my grandmother, nobody really practised the religion regularly or ritualistically. But I grew up and lived in a predominantly Muslim neighbourhood for more than three decades in cosmopolitan Bombay (now Mumbai).

Also, as a journalist in Bombay, I covered religious violence that wreaked havoc on Bombay in 1992-93, witnessed first-hand the callousness of the state in bringing justice to the survivor victims of these riots, and recorded the adverse long-term effects of official neglect that Muslims in India have suffered.

And perhaps, most pertinently, I’ve been married to a devout Muslim for over two decades.

Cultural appropriation

Yet, to construct a novel was a grave responsibility. In recent years, there have been intense debates in the literary spheres about ‘cultural appropriation’.

Lionel Shriver let loose a veritable storm last year when she defended her right to write about anything that she as a writer wanted to (Read her speech here, and Yassmin Abdel-Magied’s response here).

Closer home, our own Giller Prize winner Joseph Boyden has been hauled over the coals for claiming to be Aboriginal; his defence is that he feels like one, even if he may not be one genetically.

Well-meaning Muslim friends of South Asian origin cautioned me that my attempt at depicting a Muslim milieu in Canada would lack authenticity and suggested that I abandon the “misadventure”. I was, of course, not going to do that, mainly because I believe that imagination and craft could be better substitutes for experience.

I believe that a novelist’s primary responsibility is to tell a story competently and responsibly. Innumerable novelists have created a world in their novels that are palpably real without ever being even remotely connected to the world they create.

I have done so in Belief and I’ll leave it to the reader to judge whether the novel succeeds in portraying the complexity of being a Muslim in Canada.

Mayank Bhatt’s debut novel Belief was published in 2016 by Mawenzi House. Read our review here – Novel Explores Road to Radicalization

Mayank Bhatt is a thought leader with experience in diverse spheres such as bilateral trade promotion, administration and management of not-for-profit organisations, public relations and marketing, editorial and content management.