“All of us are descended from migrants…None of us is a native of the place we call home. And none of us is a native to this moment in time.” —Mohsin Hamid

“I felt my position as a migrant being challenged. I can’t stay silent as a writer.” —Suketu Mehta

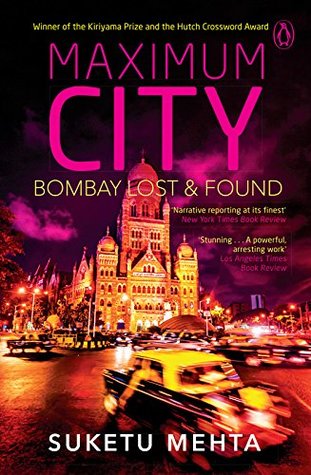

My sister Sonal, who has lived in the United States since the late 1980s, sent me Maximum City: Bombay Lost and Found by Suketu Mehta in 2005, probably a year after it was published in the US. For a person who had lived his entire life in Bombay and had covered it fairly extensively as a journalist for nearly two decades, the idea that a New Yorker could have anything new to say about one’s hometown was entirely preposterous, if not totally insulting.

But Suketu Mehta, even while talking about everything that was familiar, was saying it differently.

But Suketu Mehta, even while talking about everything that was familiar, was saying it differently.

As a journalist one had witnessed and reported the deathly carnage of the 1992-93 rioting up close, but Mehta brought alive the horror of the bloodbath with passages such as this:

“What does a man look like when he’s on fire?” I asked Sunil.

It was December 1996, and I was sitting in a high-rise apartment in Andheri with a group of men from the Hindu nationalist Shiv Sena party. They were telling me about the riots of 1992-93, that followed the destruction of the Babri Masjid in Ayodhya.

The two other Shiv Sena men with Sunil looked at each other. Either they didn’t trust me yet or they were not drunk enough on my cognac. “I wasn’t there. The Sena didn’t have anything to do with the rioting,” one man said.

Sunil would have none of this. He put down his glass and said, “I’ll tell you. I was there. A man on fire gets up, falls, runs for his life, falls, gets up, runs.”

He addressed me.

“You would bear to see it. It is horror. Oil drips from his body, his eyes become huge, huge, the white shows, white, white, you touch his arm like this” – he flicked his arm – “the white shows. It shows especially on the nose” – he rubbed his nose with two fingers as if scrapping off the skin – “oil drips from him, water drips from him, white, white all over.”

“Those were not days for thought,” he continued. “We five people burnt one Mussulman. At four a.m. after we heard of Radhabai Chawl, a mob assembled, the likes of which I have never seen. Ladies, gents. They picked up any weapon they could. Then we marched to the Muslim side. We met a pavwallah on the highway, on a bicycle. I knew him; he used to sell me bread every day.” Sunil held up a piece of bread from the pav bhaji he was eating. “I set him on fire. We poured petrol on him and set him on fire. All I thought was, This is a Muslim. He was shaking. He was crying. ‘I have children, I have children!’ I said, ‘When your Muslims were killing the Radhabai Chawl people, did you think of your children?’ That day we showed them what Hindu dharma is.” (Maximum City, 42)

‘Maximum City’ not only defined Bombay but also went on to become a genre for writing creatively about complexities that cities – especially cities in the developing world – evolve and how they transform their inhabitants.

Fifteen years later, Suketu Mehta has published another path breaking book. ‘This is Our Land – An immigrant’s manifesto’. He has obviously written it in anger, desperation and frustration at the rapid transformation of the manner in which immigrants and immigration are being treated globally.

The developed economies have, in unison, decided that they have had enough of the unwashed masses that obstinately keep on showing up at their borders, and that these immigrants are really not their problem, and that they might as well drown in the ocean for all they care. The world has suddenly become inhospitable for immigrants.

I’m a Canadian citizen, an immigrant in a country that is unique in its tolerance of immigrants. Fortunately, my experience as an immigrant has been without the horrors of racism and discrimination.

Let me hasten to clarify that while Canada by and large accepts the inevitability of immigrants to in its society; it still has not been able to evolve a mechanism that ensures the economic integration of the immigrant.

Yes, there is a crazy, right-wing fringe in Canada, too, that turns abusive and occasionally even violent towards newcomers or people who look different, but their numbers are few. It wouldn’t be erroneous to claim that most immigrants in Canada don’t experience the terror and horror their counterparts feel in some parts of Europe and the United States.

Mehta’s book while authentically portraying the conditions immigrants face in the developed world, especially in the United States and western Europe, also analyses the causes of immigration. He says it is the fear of the immigrant that is more dangerous than the immigrants themselves. He cautions that if anything perennial economic subjugation (economic colonialism) and climate change will ensure more immigration than the world is prepared to accept or even understand.

Mehta was in Toronto on two occasions recently promoting his book. In September, he participated in the maiden Toronto edition of the Jaipur Literature Festival and in October he was here to participate in the Toronto International Festival of Authors.

Meenakshi Alimchandani, litterateur and literary curator, had organised Mehta’s session at the Toronto International Festival of Literature, and agreed to my suggestion to interview Mehta after the session.

My friend Gavin Barrett, a poet and founder of the immensely successful Tartan Turban Secret Reading Series (for which he also unjustifiably credits me) agreed to my suggestion that we chat with Mehta together, giving our Bombay connection.

Mehta wanted to have “something Indian” so we went to the Indian Roti House across the Harbourfront Centre. It turned out to be a rather modest desi restaurant that served roti wraps in extra spicy chickpeas gravy.

Continue reading at The Beacon

Mayank Bhatt is a thought leader with experience in diverse spheres such as bilateral trade promotion, administration and management of not-for-profit organisations, public relations and marketing, editorial and content management.

Gavin Barrett is co-founder and Chief Creative Officer of Toronto ad agency Barrett and Welsh which focuses on creating inclusion through communications. His poetry has been published in Reasons For Belonging: Fourteen Contemporary Indian Poets, Penguin India (ed. Ranjit Hoskote), and in many other reputable literary periodicals. He co-curates The Tartan Turban Secret Readings, which promote visible minority and indigenous voices in Canadian literature.