Summer is half over, the election could be launched officially as early as Sunday — which would make it the longest campaign in modern Canadian history — and our polling shows a political landscape on ‘pause’. There are, however, some interesting developments that set the stage for the campaign proper — which won’t really get rolling until the first leaders’ debate on August 6.

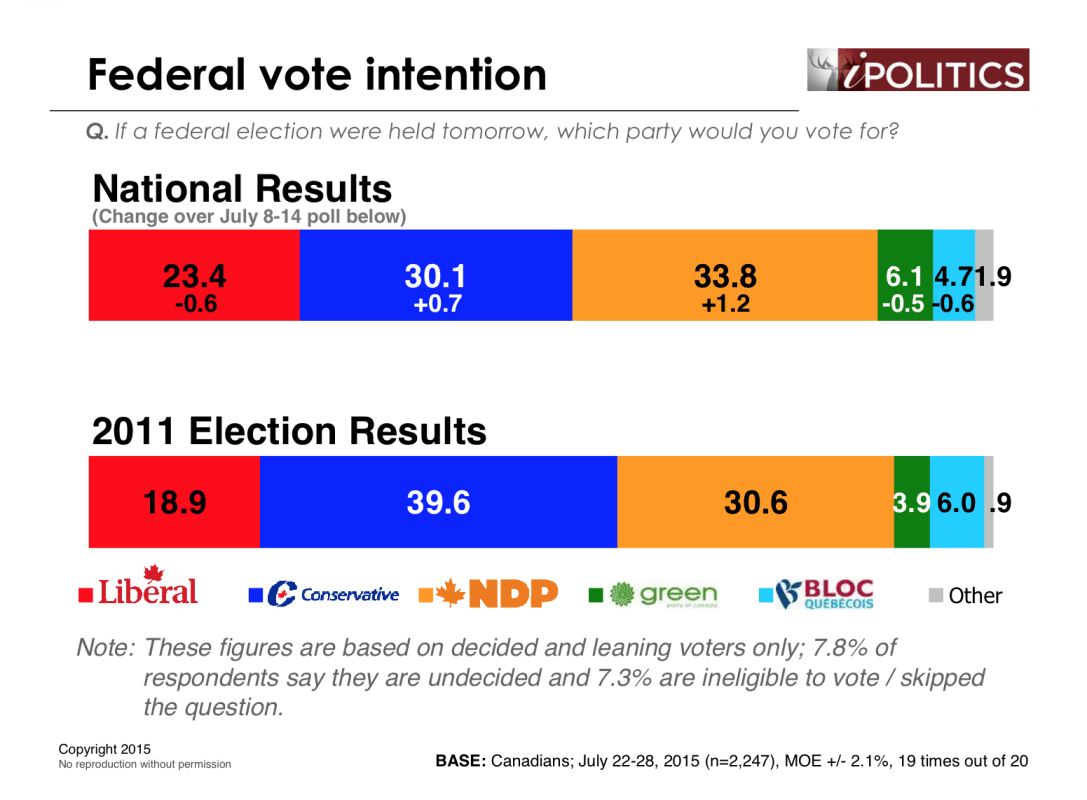

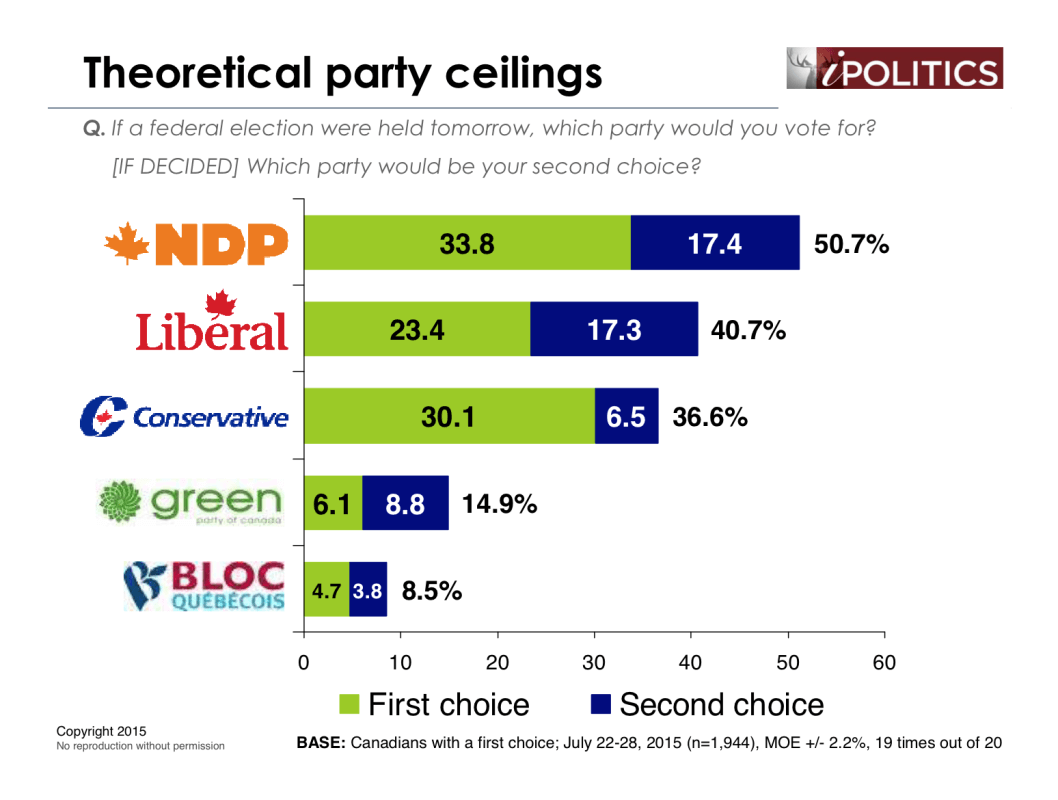

The vote intention numbers show the NDP with a clear but modest lead of 34 points, the Conservatives at 30 points, and the Liberals still in contact but significantly back at 23 points. The Bloc Québécois’s honeymoon period following the return of Gilles Duceppe seems to be drawing to a close; the party is falling back to its pre-Duceppe levels. The Green Party has also been receding in recent weeks.

In Ontario, all three parties seem to be converging into a tie. The NDP are doing quite well in Saskatchewan and although this finding should be interpreted with caution due to the extremely small sample size in the province, the longer-term trends suggest that the party has indeed gained ground here in recent months. The Liberals have clearly lost their lead with the university-educated, but our data on second choices suggests the party is still very much in contention with this group.

What, if anything, is percolating under the surface to produce these numbers? Let’s consider the three frontrunners in turn.

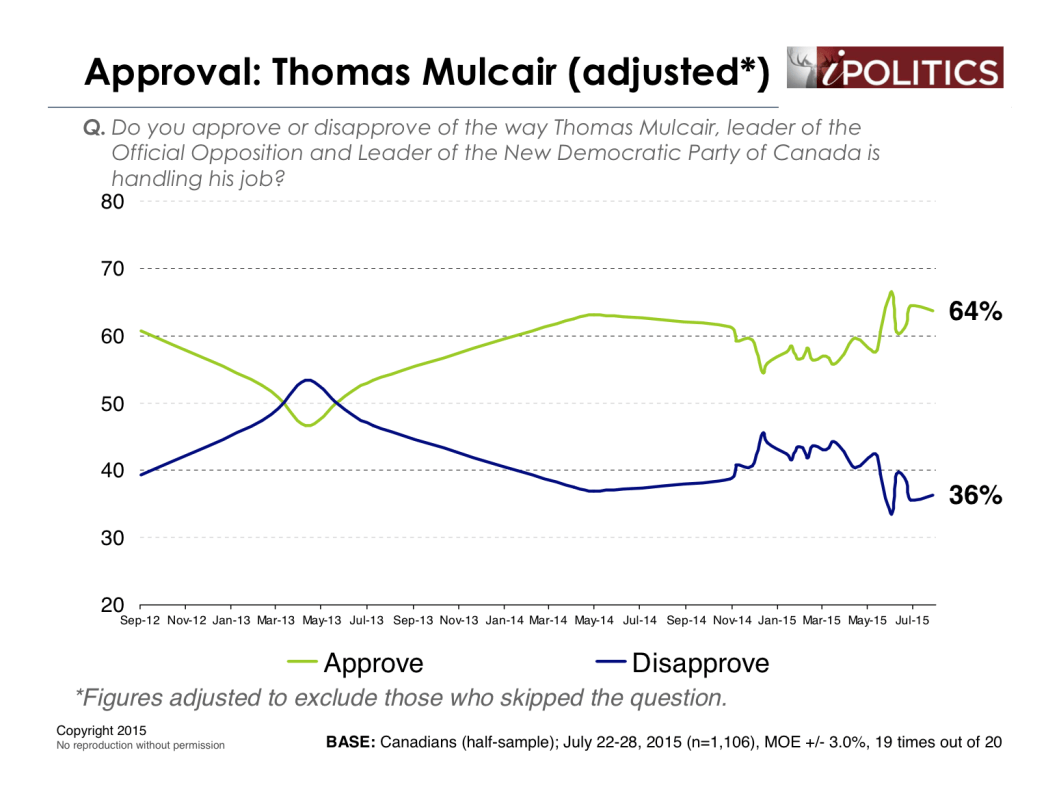

If you’re Thomas Mulcair and the NDP, what’s not to like? The New Democrats are the clear leaders in most recent polling. Mulcair has an approval advantage over the other party leaders, his team is being seen more and more as the agent of change and it has a pretty balanced regional and demographic constituency.

For the vast majority of center-left voters, the ultimate goal is not the singular success of their first choice — it’s putting an end to the Harper government and replacing it with a progressive alternative.

The key challenges for the NDP are threefold. First, it must hang on to those promiscuous progressive voters who have been swinging back and forth between the Liberal and NDP camps since 2011. Second, it must withstand the added critical attention that comes with being the frontrunner. Finally, it must convince voters that they should consider the NDP the better bet to replace the Harper government.

This last point is vitally important as it plays into Conservative strategy. The Conservatives’ consistent focus on Justin Trudeau and the Liberals as their primary rivals — their repeated attempts to paint Trudeau as callow, marginally competent and unready for power — isn’t based on lousy polling and probably doesn’t emerge from mere spite. The true motive may have been to hobble Trudeau so badly that the ballot question shifts from a choice between a coalition and Harper to a choice between the untested New Democrats and the Conservatives.

Our newest data on the public’s attitude towards coalition government reveals why the Conservatives might want to spike that possibility by keeping focus on the party now trailing the NDP by 10 points. For the vast majority of center-left voters, the ultimate goal is not the singular success of their first choice — it’s putting an end to the Harper government and replacing it with a progressive alternative. Voters may be more comfortable with some blended progressive solution than with having either the NDP or Liberals running things on their own.

Consider the following rather striking facts. First, support for any form of progressive coalition is up dramatically over 2011 — when Conservatives used the idea to spook people into opting for a stable majority government. Apparently, voters aren’t buying that argument this time. Second, the vast majority of NDP and Liberal voters would prefer a coalition to a continued Conservative minority government — and they’re relatively indifferent as to whether that coalition should be led by Mulcair or Trudeau. Their real goal is to force Stephen Harper’s exit; everything else is secondary.

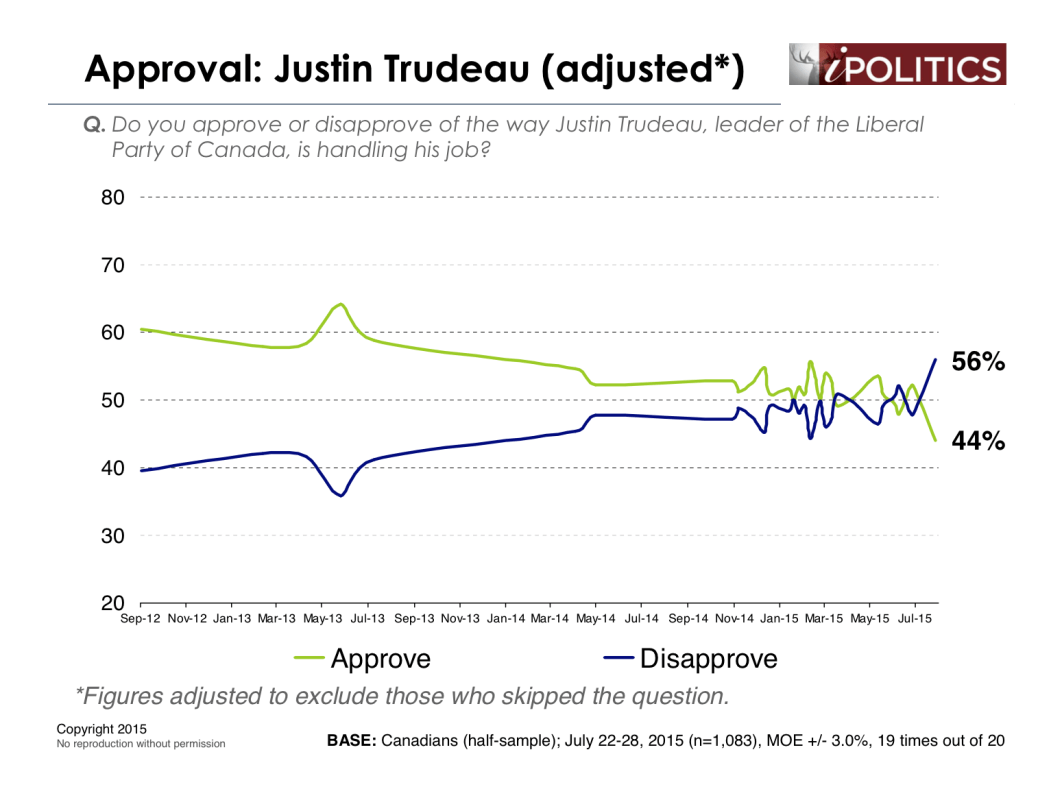

The Liberals may have chosen the wrong positions on some tough issues in the past and they may have been damaged by the relentless Conservative attack ads. They still have some strong assets, however; they can get back in the game.

The Liberal party certainly has been humbled since its lofty position of a year ago, and it’s having trouble getting its ideas across with an inattentive electorate. The Liberals may have chosen the wrong positions on some tough issues in the past and they may have been damaged by the relentless Conservative attack ads. They still have some strong assets, however; they can get back in the game. If we read our data correctly, a precondition for a Liberal recovery would be to acknowledge the gap between their hard line against a coalition with the NDP and the preferences of the people disposed to vote for them.

From our more detailed analysis of micro-regions and specific ridings, we see that there are many ridings where most progressive voters would switch horses to the progressive candidate better positioned to beat the Conservative. Just as we have seen a rise in support for coalitions (which may be a proxy for cross-party cooperation to oust the Conservatives), we see majority support for strategic voting among the majority that want to see a change of government. Given the current positioning of the parties — and the vote-splitting scenarios in play (particularly in Ontario) — we would argue that a well-developed, credible strategic voting program could spell the difference between Conservative success and failure.

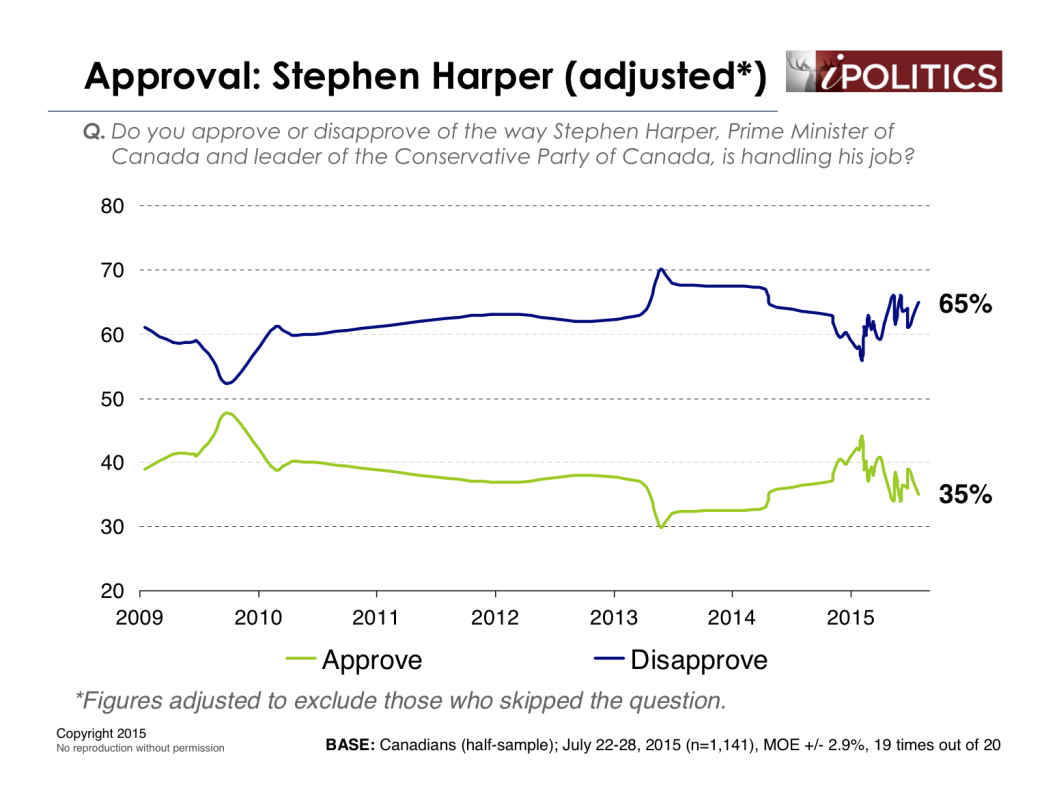

So is the Conservative party’s route to power blocked? Not at all. The government is still very much in the race and registering polling support within the range of what they had at this stage of the 2011 campaign.

The Conservatives still face a number of profound obstacles. Along with the inevitable regime fatigue, they’re fighting some of the worst-ever scores on the direction of the federal government. Stephen Harper’s approval ratings and emotional connections are lousy and still trending downward.

Canada reported today that the value of the national economy slid by 0.2 per cent in May —the fifth consecutive monthly slide.

Collective angst about middle class decline is still a critical factor; restarting middle class progress remains one of the highest priority for voters. The policy points the Harper government has chosen to emphasize — income-splitting for stay-at-home spouses and countering terrorism — are rated almost dead last in trade-off analyses. Finally, the government is 10 points shy of where it was last election — with only six per cent of voters citing them as their second choice.

So is the Conservative party’s route to power blocked? Not at all. The government is still very much in the race and registering polling support within the range of what they had at this stage of the 2011 campaign. They got a modest uptick over the ISIS ads and they got a more sizeable and important bounce from the ‘Christmas in July’ cheque bonanza. We note a significant uptick in their status among households with children — but we also note that the effect of the cheques seems to be fading, which may be one of the reasons we’re expecting an early writ drop.

So there’s a strong risk of the New Democrats and Liberals splitting the progressive vote and allowing the Conservatives to eke out a narrow victory. Nowhere is this problem more acute than in Ontario.

The most important asset for the government remains the split of the center-left. Without strategic voting or some form of tacit or explicit co-operation between the progressive parties, they risk seeing Harper retain power with an even smaller plurality than the Conservatives took in 2011. It also appears that both the Green Party and the Bloc are being caught in this dynamic; many progressive voters who like them and their leaders seem to feel the stakes are too high to support them this time.

So there’s a strong risk of the New Democrats and Liberals splitting the progressive vote and allowing the Conservatives to eke out a narrow victory. Nowhere is this problem more acute than in Ontario. We have conducted a riding-level analysis using all of our data from the past four months and — while we will not be releasing the analysis itself, given that the samples are too small — we can illustrate the problem of vote-splitting with a particularly vivid example.

In the riding of Etobicoke-Lakeshore, the Conservatives lead the Liberals by just a fraction of a percentage point, while the NDP sits more than 10 points back. Even though two-thirds of the riding supports a progressive candidate, the Conservatives stand to win by a margin of just 300 votes. In all, we have identified 31 ridings in Ontario alone where the Conservatives hold a lead of 10 points or less.

Note that we are only presenting this example for illustrative purposes and it should be treated with extreme caution due to the limited sample size and extended period. We would need to do much more extensive sampling at a riding level (as well as include cellphone-only households) to support a real — not hypothetical — strategic voting aid.

Frank Graves is founder and president of EKOS Polling.

Methodology:

This study draws on data from two separate surveys, both of which were conducted using High Definition Interactive Voice Response (HD-IVR™) technology, which allows respondents to enter their preferences by punching the keypad on their phone, rather than telling them to an operator. In an effort to reduce the coverage bias of landline only RDD, we created a dual landline/cell phone RDD sampling frame for this research. As a result, we are able to reach those with a landline and cell phone, as well as cell phone only households and landline only households.

The field dates for the first survey are July 15-21, 2015. In total, a random sample of 2,400 Canadian adults aged 18 and over responded to the survey. The margin of error associated with the total sample is +/-2.0 percentage points, 19 times out of 20.

The field dates for second survey are July 22-28, 2015. In total, a random sample of 2,247 Canadian adults aged 18 and over responded to the survey. The margin of error associated with the total sample is +/-2.1 percentage points, 19 times out of 20.

Please note that the margin of error increases when the results are sub-divided (i.e., error margins for sub-groups such as region, sex, age, education). All the data have been statistically weighted by age, gender, region, and educational attainment to ensure the sample’s composition reflects that of the actual population of Canada according to Census data.

Published in partnership with iPolitics.ca