All is decidedly not well in Quebec society today. This is especially obvious when we focus on the question of intercultural relations between the dominant francophone culture and the anglophone and allophone minorities. Our recent poll for CBC suggests half of those in Quebec’s anglophone and allophone communities have considered leaving the province in the past year — incontrovertible evidence of eroding social cohesion between these communities.

This poll features large and high-quality random samples of all of the key linguistic groups and it gives us the opportunity to assess real changes over the past year by asking the same questions in a semantically consistent fashion.

The results have been questioned by such notable polling experts as Premier Pauline Marois and others in the current PQ government who are loathe to acknowledge a serious and growing problem with the way the minorities in Quebec feel. They’ve pointed to the fact that over half of anglophones have not “seriously considered” leaving in the past year as evidence that the problem is not a problem.

“Rigged” Survey

More serious commentary came from Michel Paillé at the Huffington Post, who argues that the survey was “rigged” due to a disconnect between recent mobility patterns and the numbers who said they had considered leaving. In the two interviews that I gave on this question, I explicitly pointed out that the poll could not even remotely be considered an accurate gauge of exodus behaviour. This poll tapped feelings, not behaviour, and must be considered in light of the broader patterns from other related questions on the survey.

Acknowledging that the study was never intended as a demographic prediction of actual mobility, we must consider the question of whether the surveys show us anything truly important and new about the state of relations between francophone Quebeckers and linguistic minorities. We also acknowledge that it would be most interesting to have similar comparative data for other provinces to assess whether these findings are unique to Quebec.

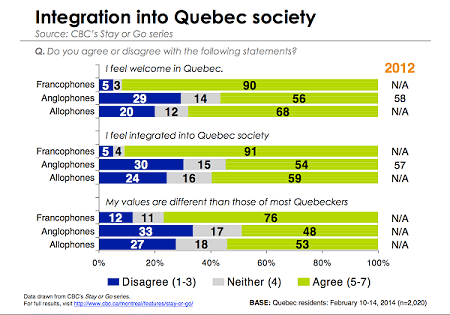

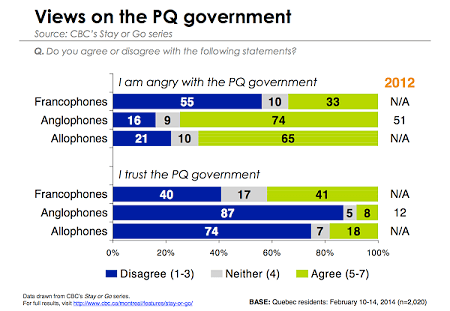

In the absence of such broader comparative testing, we will hazard a reasonable guess that the sorts of findings uncovered here are largely unique to Quebec. They show a clear and disturbing level of alienation in anglophone and allophone communities. It’s also worth noting the degree to which these two minority communities are in lockstep in terms of their growing mistrust of the current PQ government.

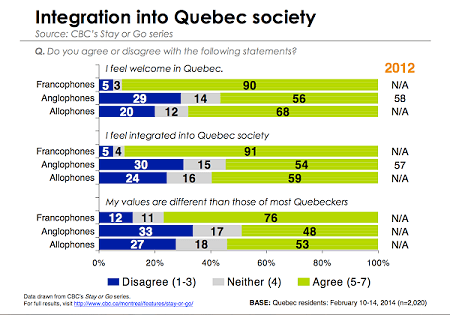

While 90 per cent of francophones reported feeling “welcome” in Quebec, a much smaller 56 per cent of anglophones share that sense of comfort. Similar jarring gaps occur across questions about whether respondents feel “integrated” or share values with most Quebeckers.

The problems of disconnection are not only normative and societal; they extend to the sense of economic opportunity. Whereas most francophones are confident that they and their children can succeed in Quebec, this level of confidence drops to about half among anglophones and allophones. This suggests that the sources of alienation are not only sociological but linked to economic prospects.

English and allophone minorities in Quebec are exhibiting an alarming and deepening disconnect from Quebec’s society, economy and politics. The problem is real and it’s getting worse.

The Catalyst

It seems clear that the catalyst which would trigger an anglophone/allophone exodus would be a successful PQ majority and an ensuing referendum. Forecasting the political arithmetic of a referendum with a significantly diminished anglophone and allophone population, it seems highly plausible that the razor thin ‘No’ victory of 1995 would be replaced with a ‘Yes’ vote.

Only 16 per cent of anglophones and 21 per cent of allophones are not angry with the Parti Québécois government — that’s a far more negative result for the PQ than in last year’s survey. Similarly, 87 per cent do not trust the government. The highly visible secular charter is seen almost universally in linguistic minority communities as a threat to human rights. Of about nine indicators which were polled both this year and last year, none improved and many significantly worsened. So Quebec’s spotty record on intercultural relationships moved from poor to awful over the past year.

Observers may question the legitimacy of the survey on the grounds that we have not yet seen a significant exodus from these diminished linguistic minorities, or that there are large portions of the population who express satisfaction and comfort. They may also ask how these indicators would look in other provinces.

All valid questions — but if they’re being used to suggest that the survey is meaningless or even “rigged”, then those criticisms are disingenuous and ignore the 800-pound gorilla in the room. English and allophone minorities in Quebec are exhibiting an alarming and deepening disconnect from Quebec’s society, economy and politics. The problem is real and it’s getting worse.

Non-francophones in Quebec are largely convinced that the PQ does not want them to stay; half of them are “seriously considering” leaving. What makes this question far more than academic is the prospect of another referendum. Rather than tracking the current horserace, we might want to examine some longer-term trend data which speak to the question of identity and attachment to Canada, to Quebec and to individual ethnic groups.

Shifts in Response

Consider the shifts in response to the question asked above in 1998 and last year. The question asks respondents to select their principal source of ‘belonging’ from the five choices provided. English Canada has been pretty stable and shows an overwhelming lean toward picking Canada as their primary source of identity. The responses from Quebec are dramatically different. In 1998, Quebeckers were less likely to pick ‘country’ but ‘province’ was only seven points ahead. We had an attachment issue, but it couldn’t have been defined as acute at that point.

Look at the dramatic change fifteen years later. The rather tepid attachment to Canada of the late nineties has faded further and ‘province’ has risen to now outstrip ‘country’ by nearly two-and a half times. If we were focusing only on francophones, the margin would be even larger.

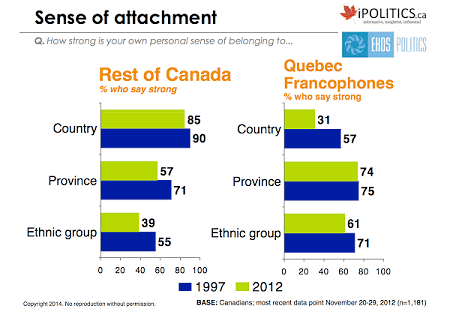

Consider another question which doesn’t force choices but asks for relative ratings of different sources of belonging. This test permits nested and plural identities — a more nuanced test of identity.

Here we compare English Canada to a sample of francophones in Quebec. The English Canada results show national attachment dominates, with declining attachment to province. It is also interesting to note that, despite rapid growth in pluralism over that period, attachment to ethnic group actually declined significantly. So much for the predictions of ethnic ghettoization and the putative threat of multiculturalism to national identity made by several authors in the nineties (e.g. Neil Bisoondath’s Selling Illusions).

Shocking Results

The more shocking results are the changes among Quebec francophones. The modest but still significant attachment to Canada in post-referendum Quebec has basically evaporated. While 85 per cent of English Canada is attached strongly to Canada, only 31 per cent of Quebec francophones share this connection.

The numbers from 1998 suggested a problem. The numbers from last year suggest that worries about Quebec separation are, in one very real sense, moot. At the level of basic emotional engagement, francophone Quebeckers have already left Confederation. It is hard to imagine that a country is viable wherein one of the founding peoples has so shallow a basic connection to that country.

Our analysis points to two major factors driving this trend. The first is the general diminution of the role and size of the federal state, one of the historical sources of national unity. Second, as the federal state atrophied, Quebec representation in that state reached a historical nadir.

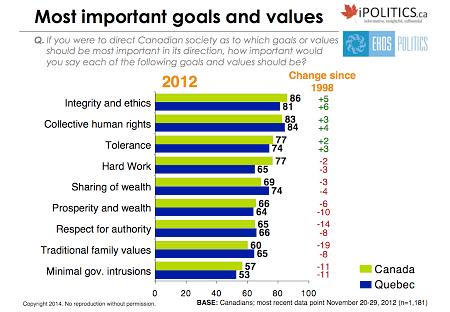

Not only is Quebec relatively missing from the federal government at the political level but the core values championed by an avowedly small-c conservative government, and the shift in Ottawa’s cultural emphasis to things like the Queen, the War of 1812 and military history — has (unsurprisingly) found less traction in a Quebec where those symbols and values lack resonance, and may even be perceived as a threat.

Frank Graves is the founder and president of EKOS Research Associates, Ltd.

The CBC commissioned EKOS Research Associates to conduct a survey of Quebecers regarding their views on a range of issues. The survey was conducted from February 10-18, 2014, and a total of 2,020 Quebec residents were interviewed by telephone as part of this study (1,013 francophone Quebecers and 1,007 anglophone Quebecers). The margin of error for a sample of 2,020 is ± 2.2 percentage points, 19 times out of 20.

For full results, go here.

Re-published with permission.