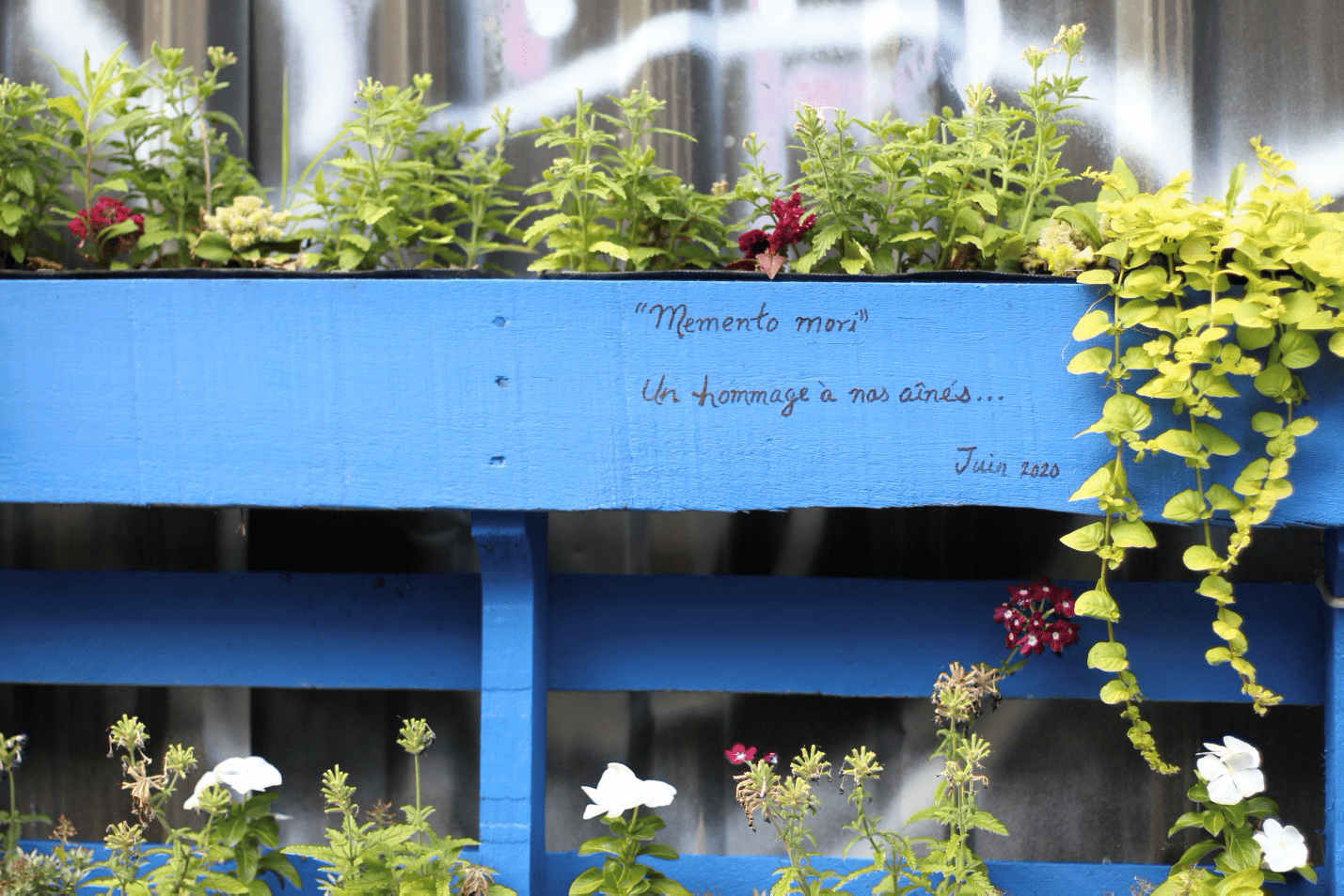

As part of her morning ritual, Adriana Enriquez-Rosas tends to the flowers in the bright blue vertical planter that leans against her fence. She has dubbed the planter, located outside her home in a busy alleyway, her “altar for the dead” (altar de muertos).

The altar is inspired by the Day of the Dead tradition in her native Mexico. On that day, people gather to pray for and remember those who have died.

In the top corner of the planter, she has used black paint to write the words, “Memento mori. Hommage à nos ainés,” which translates to “Remember you must die. Honour your elders.”

After watering the flowers, Enriquez-Rosas, 50, bikes to the Institut universitaire de gériatrie de Montreal (IUGM), the senior care centre where she has worked as a neuropsychologist for 22 years.

Her work involves using memory and attention tests to determine if patients have such neurodegenerative disorders as Alzheimer’s disease, dementia and Parkinson’s disease.

During the pandemic, the Mexican-Canadian put aside her cognitive work in order to help contain the COVID-19 outbreak at IUGM, one of the hardest-hit nursing homes in Quebec. By May, nearly 200 residents had tested positive for the virus. More than a quarter of those patients died after being infected.

“It was very hard. All of sudden, the things that I do normally don’t exist anymore,” Enriquez-Rosas says, describing her experience as “surreal.”

Instead of doing her usual work of assessing the mental capacity of seniors, Enriquez-Rosas was tasked with making sure medical staff were putting on their personal protective equipment (PPE) correctly and directing frontline workers to “hot” zones, with infected patients, or to virus-free “cold” zones.

One day, Enriquez-Rosas opened the front doors to a woman in tears, who was given only 10 minutes to say goodbye to her dying father. Then she watched as staff pushed gurneys carrying bodies to the morgue.

The virus spreads like fire

In April, the Quebec government stopped the transfer of infected seniors from nursing homes to hospitals without a doctor’s approval. However, the facilities lacked staff and sufficient PPE, and were not equipped to deal with the explosion of cases. Provincial data shows that 67 per cent of the victims who died from COVID-19 were seniors living in long-term care homes.

The IUGM came under scrutiny after dozens of deaths started to emerge. Doctors described the virus as spreading through the long-term care centre like fire.

By July, 53 residents had died at the IUGM, and the institute was among 27 public facilities in Quebec put under government supervision.

When the IUGM closed its doors to new patients in mid-March, staff was asked to take on new responsibilities. As a single mom, Enriquez-Rosas took on a less risky role that would allow her to better protect her children from infection. Instead of feeding or caring for seniors, she chose to support medical staff and the families of residents.

“I don’t have any, any family here. The borders are closed. What happens if I get sick? I can’t ask any friends to come and take care of my kids, because they have to take care of themselves and their families,” she said.

Although she was unable to practise neuropsychology during the outbreak, Enriquez-Rosas was able to support families through the grieving process by helping them say their final goodbyes through virtual ceremonies.

The new normal at work

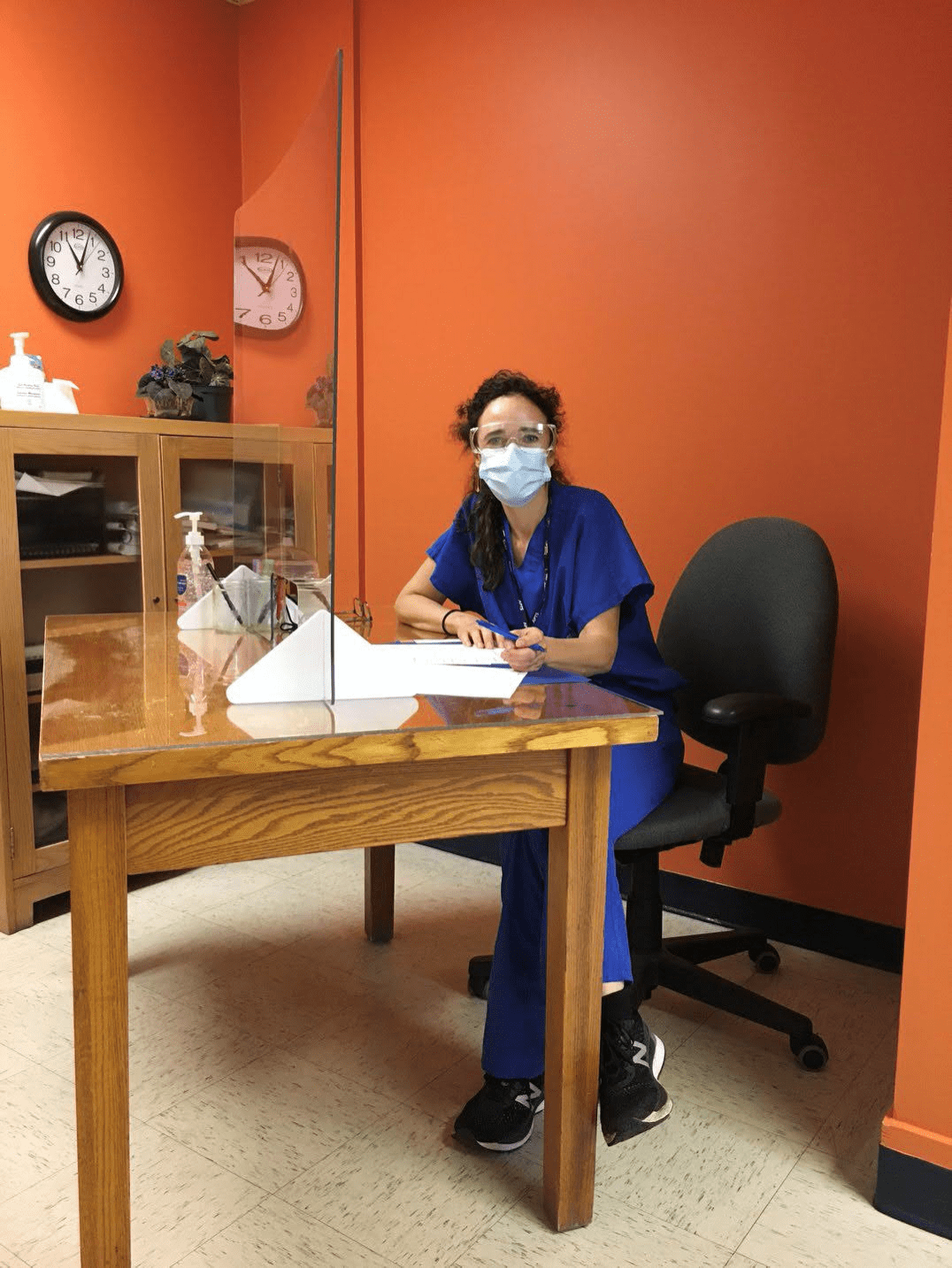

After the first wave of the pandemic halted her work for four months, Enriquez-Rosas returned to neuropsychology in July and was grateful for the opportunity to reconnect with her patients.

“I was excited to do a Zoom call the other day. I have a patient who has memory problems, so I explained to his wife how memory works so she gets less frustrated when her husband forgets to do things,” said Enriquez-Rosas, holding a hand over her chest.

“It felt good to speak to her.”

But the new normal comes with new challenges. Many of Enriquez-Rosas’ patients have difficulty hearing, and, now that face masks must be worn, it will be difficult for them to read her lips. They may also have a harder time understanding her through a plexiglass barrier. Also, virtual evaluations are not an option for most seniors over 80 years old, who find it difficult to learn new technology.

“I want to protect my patients, I want to protect myself. But I want to do a good job,” she says.

Enriquez-Rosas and her IUGM colleagues are trying to adapt by developing cognitive tests that can be done over the telephone in addition to face-to-face visits.

But more than quick fixes is needed to repair the cracks the pandemic has exposed in Canada’s health-care system. The vulnerabilities in long-term care have been known for decades. Back in 1983, a task force created by the Canadian Medical Association concluded that the standard of care in some nursing homes was “grossly inadequate.” And the situation has only worsened. A July 2020 report by the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives found that years of neglect have “left Canada ill-prepared to respond to the growing care deficit.”

The neglect of older Canadians is laid bare in government data. We now know that more than 90 per cent of coronavirus deaths in Quebec involved people aged 70 or older, even though seniors accounted for 25 per cent of the infections.

“We can’t just say it’s too bad we lost lives,” Enriquez-Rosas says. “We lost lives because of the choices made by governments we have elected over the decades that have made cuts in health care.”

She hopes her floral shrine will be a constant reminder of the need to value the lives of seniors.

“That’s why I did my altar for the dead—to pay homage but also to remind people who pass by to not forget. It’s our choice as a society, it’s our choice to take care of our seniors, of the elderly.”

Photos by Elvria Truglia.

This story is a part of the “Immigrants on the Frontlines of Fighting COVID-19” series made in partnership with The Canadian Press.

Elvira Truglia is a Montreal-based journalist who writes about the intersections of culture, politics, and social issues. She has also worked in the community, media and cultural sector as well as national and international non-governmental organizations.