In general, holding a PhD in Canada is associated with good employment outcomes. But while aggregate outcomes are good, immigrants with PhDs do not fare nearly as well as non-immigrants. In many cases, immigrants with PhDs have weaker labour market outcomes than Canadians with no post-secondary education credentials at all. Immigrants with PhDs have important contributions to make to Canada’s economic and social well-being, but a number of barriers limit their ability to effectively use and benefit from their education and skills.

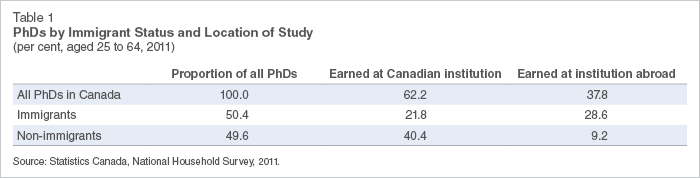

Who holds PhDs and where were they earned?

As Table 1 shows, the proportion of PhDs held by immigrants and non-immigrants in Canada is roughly equal—50.4 per cent and 49.6 per cent, respectively. Just over three in five (62.2 per cent) were earned at Canadian institutions and nearly two in five (37.8 per cent) were earned from institutions outside Canada. Of the PhDs earned at Canadian institutions, nearly two-thirds were earned by non-immigrants (accounting for 40.4 per cent of all PhDs held in Canada) and the other third by immigrants (accounting for 21.8 per cent of all PhDs). By contrast, three-quarters of doctorates earned abroad were earned by immigrants, while one-quarter were earned by non-immigrants (accounting for 28.6 and 9.2 per cent of all PhDs, respectively).

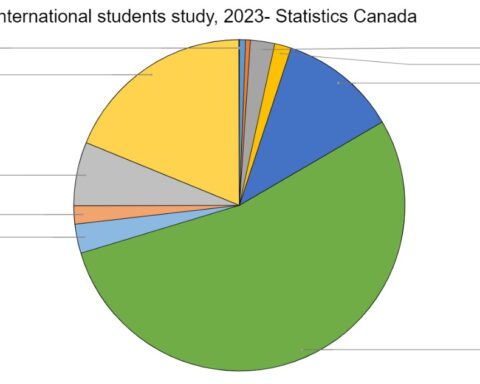

Immigrants who earned their doctorates abroad were most likely to have done so in the United States (23 per cent), United Kingdom (12 per cent), France (9 per cent), China (8 per cent), India (6 per cent), or Germany (3.5 per cent). The remaining 39 per cent were earned from institutions in a wide diversity of countries. Nearly all of the non-immigrants who earned doctorates abroad did so in one of only three countries—the United States (67 per cent), United Kingdom (18 per cent), and France (6 per cent).

Location of study natters more for immigrants than non-immigrants

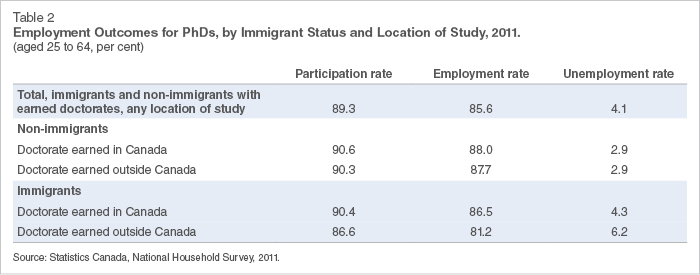

Employment outcomes are significantly weaker for immigrant PhDs than they are for non-immigrant PhDs. Non-immigrants, whether they earned their doctorates in Canada or abroad, have a labour force participation rate over 90 per cent, an employment rate of 88 per cent, and very low unemployment at 2.9 per cent. Immigrants who earned their doctorates in Canada have similar participation and employment rates, but their unemployment rate is noticeably higher at 4.3 per cent.

For immigrants who earned doctorates from institutions outside Canada, the situation is troubling. This cohort has lower labour force participation and employment rates, and an unemployment rate of 6.2 per cent—more than twice the rate of non-immigrants with PhDs (see Table 2) and equal to the unemployment rate for all education levels in Canada. Collectively, the nearly 50,000 immigrants in Canada who earned their doctorates abroad enjoy virtually no employment advantage when compared with Canada’s population regardless of educational attainment. That said, immigrant PhDs fare better than immigrants without PhDs in the Canadian labour market.

What explains the difference in outcomes?

Immigrants are less likely than non-immigrants to have studied in a country whose credentials are easily recognized and trusted by Canadian employers. While immigrants who earned their doctorates in the United States had an unemployment rate of only 3 per cent—in line with the unemployment rate of non-immigrants with doctorates—less than a quarter earned their doctorates from the United States. Immigrants who earned their doctorates in countries other than the U.S. or U.K. experience much higher rates of unemployment.

But location of study explains only part of the difference. Regardless of where they earn their PhDs, immigrants face a range of employment barriers, including less-developed employment networks, language barriers, and racism. Immigrants with PhDs fare much better than immigrants without PhDs, but they face difficult transitions, achieve only a slim advantage over non-immigrants with lower education, and continue to lag well behind their non-immigrant peers with PhDs.

Understanding and addressing the many barriers to immigrant PhDs is critical to ensuring that both they and Canada’s economy and society as a whole can benefit from the advanced education and skills they have obtained. The ongoing work of The Conference Board of Canada’s Centre for Skills and Post-Secondary Education and National Immigration Centre explores various dimensions of the challenges facing immigrants—those with and without PhDs. It will shed light on changes that might be required as to how immigrant PhDs are educated and trained in Canada, as well as how immigrants are selected and integrated into the Canadian economy and society more generally. Watch for future commentaries and reports from both centres in 2015.

Daniel Munro has over ten years of experience in research and policy analysis on education, skills, innovation, and science and technology issues. He is is a Principal Research Associate in Public Policy at The Conference Board of Canada, and Lecturer in Ethics in the Graduate School of Public and International Affairs at the University of Ottawa.

Re-published with permission.