The 75th anniversary of the Battle of Hong Kong is being commemorated across Canada by veterans and survivors of Japanese occupation and their families. About 2,000 Canadians fought to defend Hong Kong against Japanese occupation in Canada’s first combat mission of the Second World War.

“They were relatively inexperienced. A lot of them were new recruits,” says Patrick Donovan, curator of the exhibit Hong Kong and the Home Front at the Morrin Centre in Québec City, Quebec. “A lot of them learned to fire their rifles on the boat ride over.”

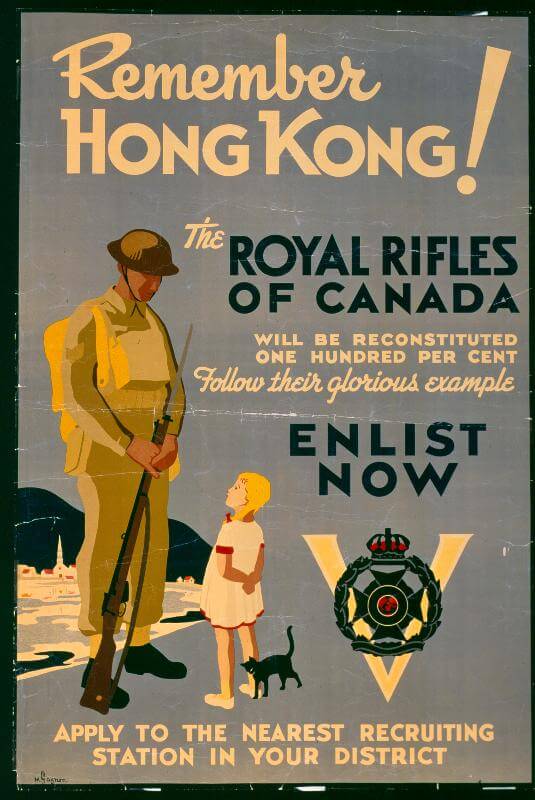

The Royal Rifles of Canada, Quebec City’s main English-speaking regiment, and the Winnipeg Grenadiers were sent to Hong Kong in fall of 1941 to join a battalion of commonwealth forces totalling 14,000 troops.

On December 8, 1941, Japanese aircraft began attacking Hong Kong. A day earlier, they had attacked Pearl Harbor. The defence of Hong Kong ended almost three weeks later when Canadian and other defending troops were forced to surrender. Among Canadian troops, 290 were killed and 493 were wounded.

Hong Kong and several other countries and territories were occupied by Japan for the duration of the war. On November 4, 1948, the International Military Tribunals for the Far East found 25 Japanese military and government officials guilty of committing war crimes and crimes against humanity during the Second World War.

Personal experiences of war

“The occupation is something we never talk about,” says Sovita Chander, whose father grew up in Japanese-occupied British Malay. The former president of the Literary and Historical Society of Quebec, which runs the Morrin Centre, Chander says she learned about this period of her father’s life through his memoirs.

“I can’t imagine my own children — now in university — having to go through that, and my heart goes out to my parents who were so young at that time,” says Chander.

“A lot of them learned to fire their rifles on the boat ride over.”

Her father’s memoirs describe how at the age of six, he and his family spent a day in an underground shelter as the Japanese army passed overhead. The next day, he watched his father stay with a dying Indian soldier, who he buried the next day.

“Despite the atrocities, horror, and depravation, he held no animosity for the former occupiers,” says Chander of her father, noting that Malaya was also a British colony. “He developed an international outlook that was liberal and tolerant.”

Chander says it’s important to tell the story of the people from the Québec City region who were in Hong Kong, including some people who were involved with the Morrin Centre at the time.

Remembering tragedy

“We tend to focus a lot on the victories of the war and it tends to glorify the whole business of war,” says Donovan of the Centre’s exhibit. “It’s important to look at some of the defeats, and this story is a tragedy.”

He says the soldiers who were not killed were held in Japanese Prisoner of War camps for the duration of the War. Many prisoners died of malnutrition or diseases related to lack of food.

According to Veterans Affairs Canada, more than 550 of the almost 2,000 Canadians who went to Hong Kong never returned.

“It’s important to look at some of the defeats, and this story is a tragedy.”

“The Japanese still have not come to terms with what they did in the Second World War,” says Judy Lam Maxwell, whose mother lived under Japanese occupation in Hong Kong as a child.

“She had told me that because her father was a doctor, he could hide the kids in the hospital and they would be safe from harm,” says Lam Maxwell. “My mom, her siblings, and her mom are fortunate to have survived.” She says that her grandfather, or Goong Goong, was tortured by the Japanese, but also survived.

Commemorating the Battle

Lam Maxwell heard the stories of other survivors when she travelled to Hong Kong with ex-servicemen from Canada several years ago. She collected newspaper articles from Canada and Hong Kong that will be part of an exhibit at Centre A in Vancouver, B.C. later this year to commemorate the Battle of Hong Kong.

“Many of the Canadians and immigrants from Hong Kong living in Canada do not know this history and it’s important for museums and historians to share the significant link between Canada and Hong Kong,” says King Wan, president of the Chinese Canadian Military Museum Society.

The Chinese Canadian Military Museum in Vancouver will showcase “Force 136” on May 14 as part of Asian Heritage Month to commemorate Chinese-Canadians who joined the Special Operations Executive in East Asia during the war.

Many prisoners died of malnutrition or diseases related to lack of food.

He notes that at the time, people of Chinese descent were prohibited from joining Canada’s armed forces. While many were rejected, recruiters who were eager to meet quotas accepted some Chinese-Canadians who enlisted.

The policy against Chinese recruitment was rescinded after the British government pressured the Canadian government to recruit Chinese-Canadians, as they could easily assimilate into East-Asian society and work for the army undercover. More than 700 Chinese-Canadians joined the Canadian army, mostly in British Columbia.

The museum will also commemorate the Battle of Hong Kong with another exhibit in the fall.

For Wan, whose family immigrated to Canada from Hong Kong, he feels these events are especially important so that we remember the service of both Chinese and Canadian soldiers who served in Asia and in the Battle of Hong Kong.

A poster recalls the Battle of Hong Kong to enlist new recruits to join the Royal Rifles of Canada, based in Quebec City. Source: Canadian Museum of History.