The face of Canada’s immigration system has been changing drastically. With the federal government scaling back on settlement service funding in parts of central Canada, the situation is even bleaker in the Atlantic region, where funding is hard to come by.

The Refugee and Immigrant Advisory Council (RIAC), for example, is on life support. With the recent uncertainty in the value of oil, the private businesses who were RIAC’s prominent donors were forced to cancel their regular donations. The non-profit NGO has had to lay off its staff and is surviving month to month on private donations and volunteers.

“The drop in oil has affected us all,” says Jose Rivera, executive director of RIAC. Much like Alberta, oil is the dominant force in Newfoundland’s economy.

RIAC’s decline comes at a precipitous time for the province. According to a recent article in the Globe and Mail, by John Ibbitson, jobs are disappearing, young people are leaving and the population keeps getting older.

As a solution, Ibbitson urges the province, and other regions in Atlantic Canada facing similar challenges, to “aggressively recruit immigrants, to slow the aging of the population while injecting new energy and ideas.”

“In fact, newcomers are happy to be here, but they don’t get the support they need. They leave for the big cities because they think that’s where they’ll get help.” – Jose Rivera, Refugee and Immigrant Advisory Council, Newfoundland

Traditionally, however, Atlantic Canada has not been a hub for newcomers. Governments have been sluggish in developing recruitment strategies.

“Conventional wisdom is that newcomers would rather go to cities like Montreal, Toronto, or Vancouver,” explains Rivera.

“In fact, newcomers are happy to be here, but they don’t get the support they need. They leave for the big cities because they think that’s where they’ll get help.”

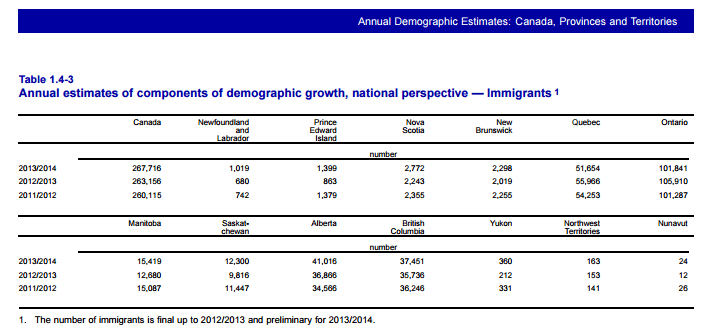

While settlement services in central Canada are far from ideal, they do seem to be more of a priority there than with the Newfoundland government. This is presumably because the number of newcomers settling in the Atlantic province is low. According to Stats Canada, in 2014, Newfoundland only took 0.4 per cent of Canada’s total immigrants.

However, Rivera believes that if Newfoundland were to commit to immigration, the numbers would increase.

Rivera came to St. John’s, Newfoundland, as a refugee from Columbia in 2002. He started working with RIAC in 2004.

In the last 10 years, the organization’s annual budget has grown from $5,000 to $100,000. RIAC has come to play an integral role in helping immigrants and refugees in a province that has historically struggled in retaining newcomers.

“We are in danger of losing all the work and progress we’ve accomplished,” Rivera says.

“There is no manual [newcomers] can just pick up at the airport. It’s our job to fill that gap of knowledge.” – Jose Rivera, Refugee and Immigrant Advisory Council, Newfoundland

RIAC receives no government funding. In fact, The Association for New Canadians is the only organization that offers government funded services in Newfoundland. Rivera says this is insufficient, as in other parts of Canada the government makes much more significant investments in settlement.

Newcomers need more robust services when they come to Newfoundland.

“There is no manual they can just pick up at the airport,” Rivera says. “It’s our job to fill that gap of knowledge.”

A Leading Example

As Ibbitson points out in his article, Prince Edward Island (PEI) is bucking the trend in Atlantic Canada.

By making extensive use of the Provincial Nominee Program (PNP) and a sophisticated coordination of its settlement services, PEI has been able to attract and retain newcomers in droves.

According to PEI’s Association for New Canadians (ANC), PEI has 0.4 per cent of Canada’s population and it attracts 0.5 per cent of the nation’s immigration. Meanwhile, Newfoundland, with 1.4 per cent of the country’s population, attracts only 0.4 per cent of its immigrations.

“We still haven’t gotten over ‘Islander’ mentality. That people born in the province are ‘Islanders’ and that newcomers are ‘Come From Aways.’ We are all Islanders.” – Craig Mackie, PEI Association for New Canadians

As well, in the past eight years, PEI’s retention rates have improved from approximately 20 to over 40 per cent.

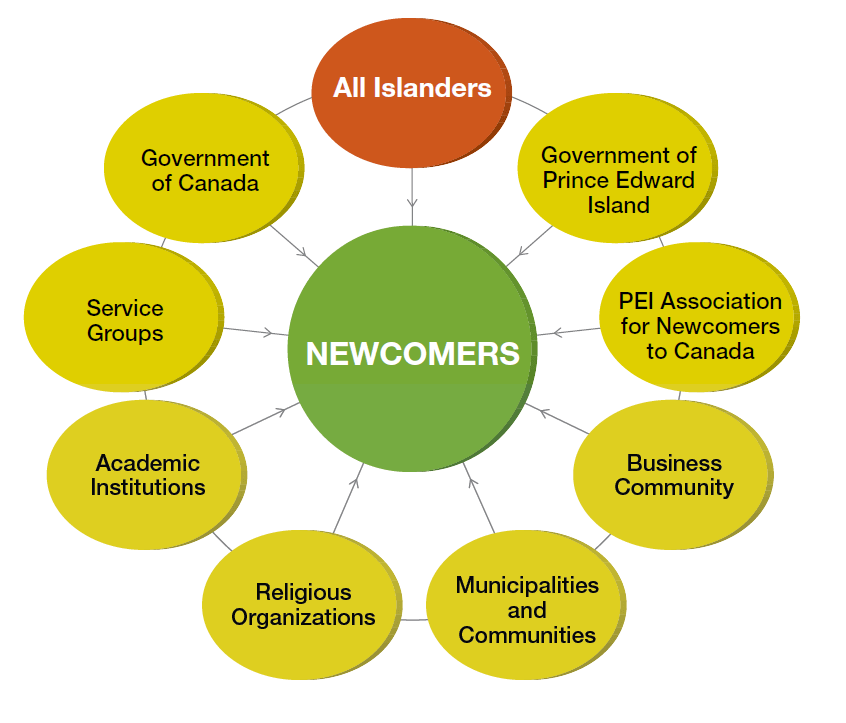

The secret to PEI’s success is how the province integrates its settlement services with various stakeholders, a strategy it developed in 2010 (seen below).

Much of this is achieved by Island Investment Development, Inc. (IIDI), a crown corporation that develops, implements and manages programs and services focused on increasing PEI’s population.

Much of this is achieved by Island Investment Development, Inc. (IIDI), a crown corporation that develops, implements and manages programs and services focused on increasing PEI’s population.

Craig Mackie, executive director of PEI’s ANC, explains, “The three keys to integration and retention are learning the language, employment and social inclusion.”

The province offers free English language classes – funded by the federal and provincial governments – for permanent residents.

In regards to employment, PEI’s PNP has two main categories to address its economic needs: the labour impact category and the business impact category.

The former is geared towards attracting skilled or temporary workers and is employer-driven. The latter is meant to attract foreign nationals to invest and manage a business in PEI.

Applicants who meet the criteria enter into an escrow agreement with the province to 100 per cent own, partially own or begin investing in a business in the province.

From 2013-14, PEI had 389 applicants for the 100 per cent ownership stream.

Mackie says the ANC is busy working on the third element, social inclusion. To that end, the ANC recently organized a gathering of over 100 people to discuss ways to make the province more welcoming to newcomers.

“We still haven’t gotten over ‘Islander’ mentality,” Mackie says. “That people born in the province are ‘Islanders’ and that newcomers are ‘Come From Aways.’ We are all Islanders.”

Missed Opportunity

Like PEI, Newfoundland also struggles with an “Islander” mentality.

“Friendly people don’t necessarily make friends,” remarks Lois Berrigan, settlement services manager at the ANC in St. John’s, Newfoundland.

Though Newfoundlanders have a reputation for hospitality and friendliness, “Come From Aways”, or “CFAs”, are terms that are heard often. Though rarely intended with malice, the separation is obvious.

Ben Waring, the diversity coordinator at the St. John’s ANC, agrees. “The population has been homogenous for so long. There’s going to be growing pains.”

Nonetheless, there have been high profile success stories of integration in the province. The CBC series “Land and Sea” ran an episode entitled “The Southern Shore Sri Lankans,” which profiled two Sri Lankan mechanics and their families, who’d immigrated to the rural town of Cape Broyle.

Rural, or “outport,” Newfoundland is the sort of homogenous area that would presumably struggle with newcomers, so stories like these illustrate how the province may be ready to embrace multiculturalism.

Furthermore, of the Atlantic region, Newfoundland is best positioned economically to invest heavily in a more robust settlement network. It is also arguably the most in need of immigration.

Oil revenue has helped fill government coffers, but unemployment remains high at 15.6 per cent.

And, by 2020, the province anticipates that 70,000 jobs will be available, most of which will be the result of attrition, but 7,700 of those will be new positions. Of these positions, 66.7 per cent will be in management occupation and will require a post-secondary education.

“We need to increase our population. Soon, we’ll fall back to ‘have-not’ status. We’ve got to do something.” – Lois Berrigan, Association for New Canadians, St. John’s, Newfoundland

Moreover, Newfoundland is old and getting older. According to the 2014 census, Newfoundland had the highest median age (44.6) and it is projected that 31 per cent of the population will be 65 years and older by 2036.

By mimicking PEI, Newfoundland could lower its unemployment by injecting the economy with new investors and entrepreneurs, while simultaneously rejuvenating the population with young families.

“We need to increase our population,” says Berrigan. “Soon, we’ll fall back to ‘have-not’ status. We’ve got to do something.”

Rivera agrees. “For our needs, the province needs at least five settlement services working together.” At present there are three, the ANC, RIAC, and the Multicultural Women’s Organization of Newfoundland and Labrador.

Nonetheless, the issue right now is quality, not quantity. There is a lack of cooperation among stakeholders and services. Newcomers are not able to cut through the red tape and access the services they need; Newfoundland needs it own Island Investment Development, Inc. of sorts.

The New Brunswick Multicultural Council continues efforts “to make New Brunswick the province of choice for … newcomers” and even tiny Cape Breton in Nova Scotia is “dreaming big”.

For now, though, Newfoundland, and the rest of Atlantic Canada, would be wise to imitate PEI – the overachieving sibling.

In the previous 360º instalment, NCM looked at settlement services in Ontario. The final piece in this series will move westward to examine the state of settlement in provinces like British Columbia and Manitoba.