Black Canadian fashion entrepreneurs like Paul Cornish and Winston Kong might not be household names today, but they broke down barriers in Toronto’s fashion scene in the 1970s and 1980s. These designers, their fashions, and their aesthetics created opportunities for Black models to appear in major publications, while also broadening Canada’s fashion silhouette to include people of African descent.

Like the Jamaican-born Cornish and Kong, most fashion trailblazers from the Caribbean arrived in Canada following changes to immigration law that occurred first in 1962, when the federal government ended race-based immigration policies, and then in 1967, when a points system was introduced that emphasized educational qualifications, proficiency in English or French, and work experience, rather than ethnic origin, as determinants of immigration.

Between 1965 and 1979 approximately 194,000 Caribbean immigrants of Black, Chinese, and South-Asian descent arrived in Canada. A decade later, Black newspapers such as Share (founded in 1978), Pride (founded in 1983), Caribbean Camera (founded in 1990), and Dawn (founded in 1991) had achieved wide circulation within Metropolitan Toronto and, to a lesser extent, other urban centres. Black beauty products were sold in department stores like Eaton’s and Simpsons, and a new generation of Black Canadians entered the fashion industry as designers, models, hairstylists, photographers, and garment professionals such as tailors and seamstresses.

If there is a central thread running through the story of Black fashion in Canada, it’s that the Caribbean immigrants of the 1960s and 1970s were often the first Black people to appear on Canadian magazine covers, the first to walk the runways at fashion shows, and the first to launch clothing lines geared towards a Black consumer market. Their journeys were not easy. Racism and prejudice were rampant, and many had to challenge stereotypes not only about Black people but also about Black aesthetics. Some designers chose not to emphasize their race, perhaps seeking to reach a wider audience. It took American-born, Paris-based designer Patrick Kelly — who died at the age of thirty-five in 1990 due to complications of AIDS — to push mainstream media to acknowledge his race, while creating clothes that crossed or even erased ethnic lines and appealed to people of all backgrounds.

By remembering their names, learning about their biographies, and revisiting their accolades, we gain a deeper appreciation for Canada’s Black fashion trailblazers.

DANCE COLLECTION DANSE/LILIANA REYES

Ola Skanks

The life and career of Ola Skanks serve as a reminder that some Caribbean-Canadian Black fashionistas were born here; their ancestors arrived during an earlier and smaller immigration wave that took place in the first decades of the twentieth century. A choreographer, teacher, educator, and activist, Skanks was born in Toronto in 1926. Her father was from Barbados, and her mother was from St. Lucia.

“My sister and I used to go to the movies and watch Fred Astaire and all the tap dancers that performed at that time, and we copied them … that was the beginning. And then I became very interested in African art, in my heritage,” Skanks said in an interview on the occasion of her 2018 induction into the Encore! Dance Hall of Fame, which recognizes Canadians with major achievements in dance. In the 1970s, Skanks invited members of Toronto’s Caribbean community to events at her home, where she modelled traditional African fashions like the dashiki, a loose, brightly coloured tunic originally from West Africa.

Dance scholar Seika Boye described Skanks as a groundbreaking dance and fashion artist who combined modern Western art with traditional African diasporic forms. “Ola Skanks was both a performer and a teacher, alongside her exceptional skills as a seamstress and fashion designer,” Boye said. Skanks died in August 2018 at the age of ninety-two, five months after her induction into the Encore! Dance Hall of Fame.

DANCE COLLECTION DANSE/KENNEDY

COURTESY DONNA TAYLOR

Marianne Katerina Skanks Howell

Model, dancer, and designer Marianne Katerina Skanks Howell was born in Toronto in 1953. The daughter of Ola Skanks, she often worked with her mother to design fashions that combined Western influences with traditional African diasporic elements. Although she died of lupus in 1993, Howell left her mark on Canada’s fashion industry with her elegance and grace.

“By all accounts [Marianne] was a part of that first wave of Black models that combined graceful choreography and an elegant projection of Black beauty,” said Charmaine Gooden, founder of the Black Fashion Canada Database. “People say her dance background showed in the way she interpreted different moods on the runway. She was known for her walk. … I think her impact was the fact that she represented, opened doors for other Black models, and was part of the early foundation group of Black models in Toronto.”

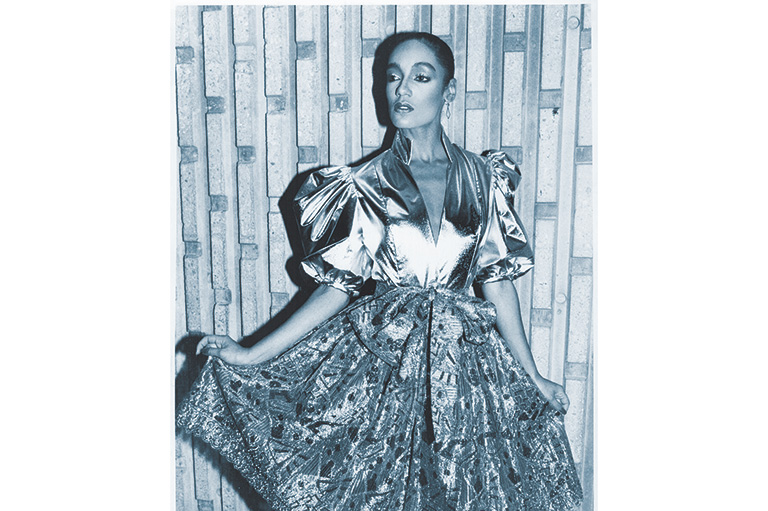

COURTESY OF ETHNÉ GRIMES-DE VIENNE / PHOTOGRAPHER, BOUDEWIJN NOTENBOOM

Ethné Grimes-De Vienne

Born in 1956 in Port-of-Spain, Trinidad, Ethné Grimes-de Vienne worked as a model for eighteen years, making her first runway appearance in 1978 with the Fashion Designers Association of Canada in Montreal. When Grimes-de Vienne entered Canada’s predominantly white modelling industry in the 1980s, Black models often worked with makeup artists and designers who had no experience with darker skin tones and natural Black hair. “Of course, I knew that I was treated differently, maybe because I was taller, or skinnier, blacker, or maybe even because I didn’t have much hair!” Grimes-de Vienne recalled in an interview with the online magazine Black Fashion Canada. Often the first or only Black model on fashion shoots, Grimes-de Vienne had a thriving career. She appeared regularly in the Montreal Gazette at the request of its legendary fashion editor Iona Monahan. Today, Grimes-de Vienne and her husband, chef Philippe de Vienne, own and operate Épices de Cru, a spice company in Montreal.

GETTY/TSPA_0052693F

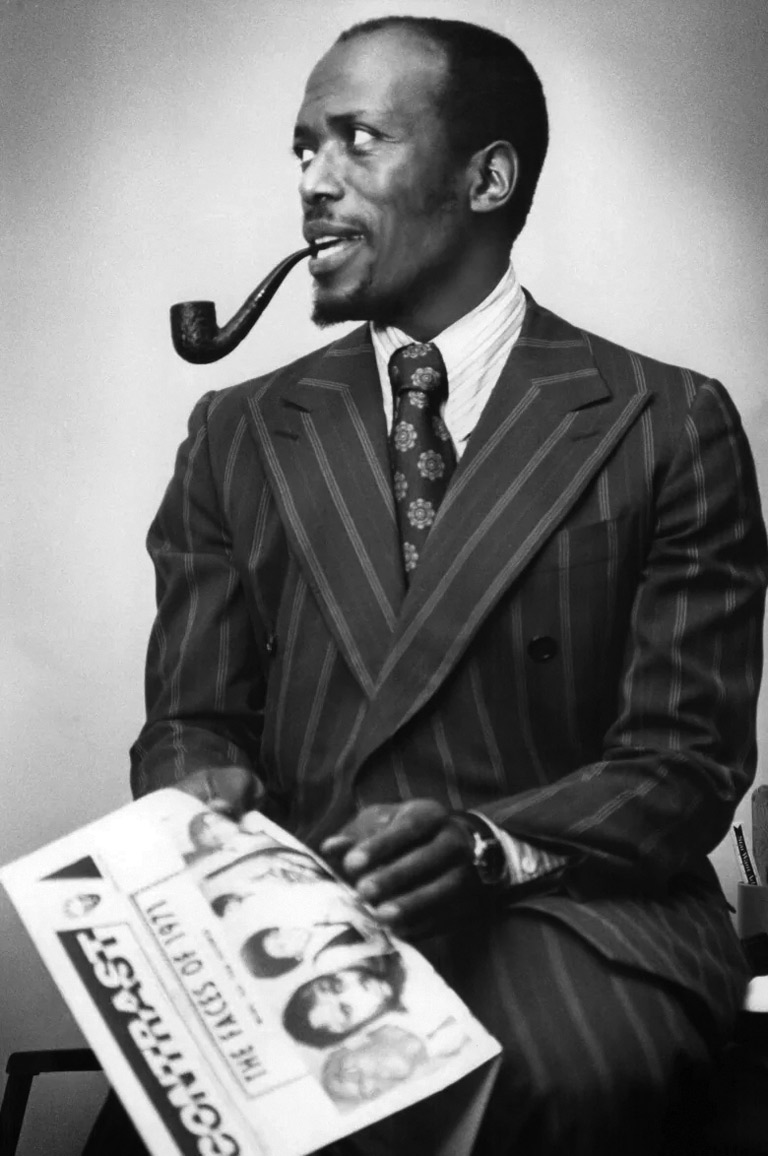

Al Hamilton

In 1969 Al Hamilton and Olivia “Babsy” Grange co-founded Contrast, a pioneering Toronto weekly newspaper that covered the Black community. In addition to reporting the news, Contrast covered arts events and fashion shows like those hosted by Ola Skanks.

“Contrast championed African liberation, social justice, and social change,” Toronto business owner Sandra Young said at a 2016 event to celebrate the newspaper’s legacy. “Contrast was a magnet for all budding Black journalists — and there were many of us with talents honed around the world — who found the newspaper an oasis in a bleak landscape where Blacks, for the main part, were not seen as reporters, editors, and certainly not as on-air presenters,” wrote journalist and academic Cecil Foster in a 2017 online opinion piece for CBC.

Contrast ceased publication in 1991, but many of its journalists went on either to found or to work for other media outlets. They included editors Harold Hoyte, who founded the Nation newspaper in his native Barbados, and Lorna Simms, who launched the multicultural newsmagazine Dawn. Hamilton died in 1994. His legacy lives on in Toronto Metropolitan University’s Al Hamilton Award in Journalism.

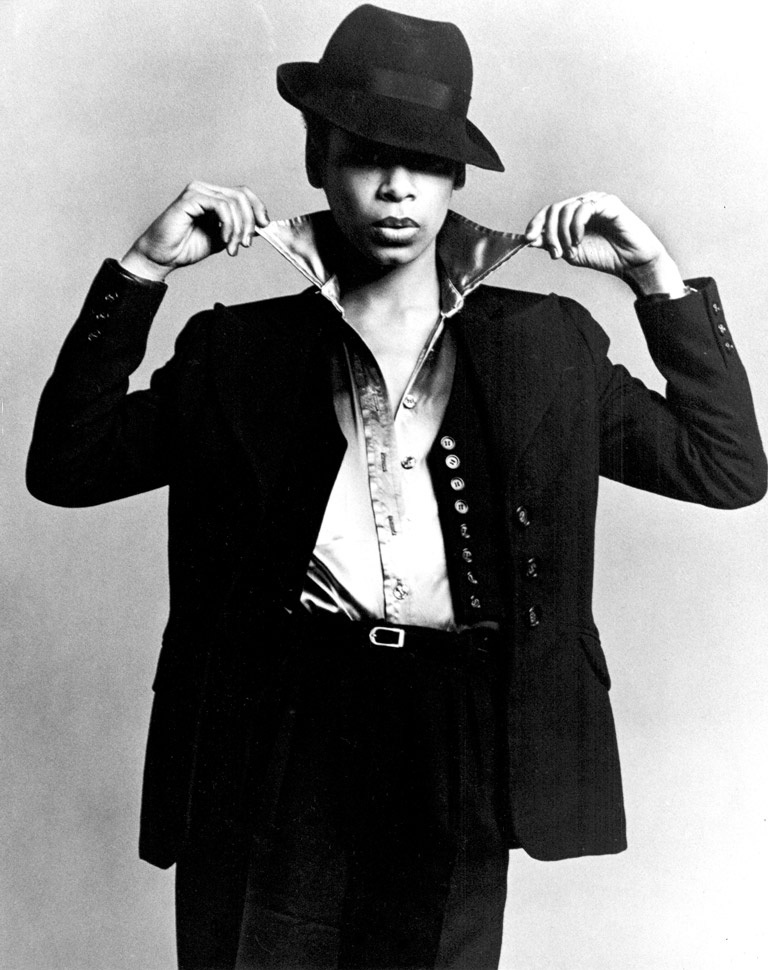

Paul Cornish

Paul Cornish was born in 1959 in Kingston, Jamaica. After immigrating to the United States with his family, he studied at New York’s Fashion Institute of Technology. In the late 1970s he moved to Toronto, where he made his way in the fashion industry by connecting with Black hairstylists, makeup artists, and others who showed him the tricks of the trade in Toronto’s fashion scene. Mainstream newspapers began to cover Cornish’s work by the early 1980s, and an April 28, 1983, article in the Toronto Star dubbed him “the cocktail dress king.”

Cornish was successful, but he wasn’t always acknowledged as a Black designer. Media reports often described him as being born in the United States, or they did not mention his ethnicity and lineage at all. “The mainstream media didn’t talk about Black identity back then,” recalled Charmaine Gooden, founder of the Black Fashion Canada Database. “Not unless you were catering exclusively to the Black community, which [Cornish] wasn’t.”

GETTY/TSPA_0006715F

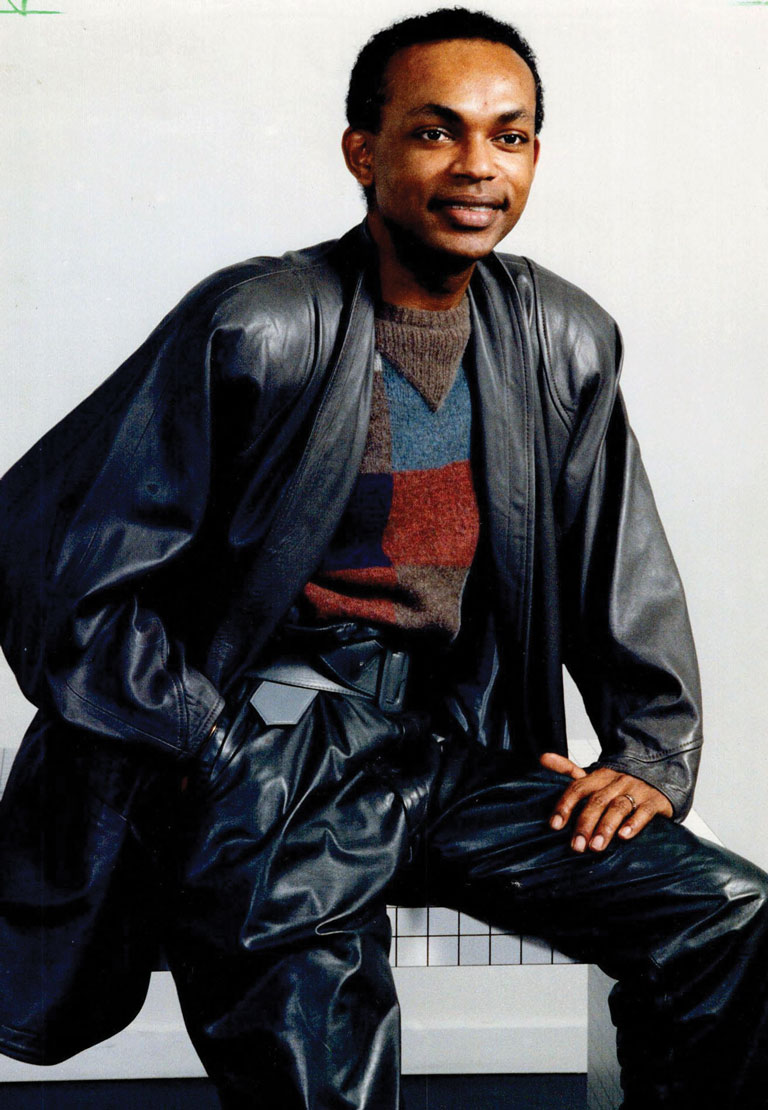

Winston Kong

Born in Jamaica in 1934, Winston Kong became one of Toronto’s leading couture fashion designers; his clothing was custom-fitted with unique, often handsewn embellishments. After attending New York’s Fashion Institute of Technology and working as an assistant designer in Manhattan, he headed north to Toronto in 1964. In 1966, with $1,200 in savings, Kong opened his own boutique with a special focus on women’s evening gowns. “It’s easy to recognize a Winston dress,” observed a Toronto Star feature in December 1984. “If it isn’t red or black, it’s likely to be a flamboyant, exquisite jewel tone, fitted in the bodice, with a glamorous full skirt.”

With a Chinese father and a Black mother, Kong’s family reflected the multiracial diversity of Jamaican society. Chinese people first arrived in Jamaica as indentured workers in the nineteenth century. By the 1940s, most people in the island’s Asian community were Jamaican-born, and many, like Kong, were of mixed Chinese and African descent.

Kong died in 2005, but his legacy remains alive. Despite having a Jamaican accent and being one of Canada’s few non-white designers of his time, Kong beat the odds to achieve success. His grit and creativity influenced his nephew Jeffrey Kong, who is also a fashion designer as well as a mentor at the non-profit Toronto Fashion Incubator. “There were race issues around, [but] it rarely existed in the confines of his atelier,” recalled Jeffrey Kong, who credits his uncle’s art and métier — “elegant, personal, timeless, sublime, and chic” — coupled with his charisma, personality, and close relationships with his clients, as reasons for his success.

“Winston was a huge influence in my career. He nurtured and opened my world to not just fashion but also culture, the arts, opera, classical music, gastronomy, creative thinking, being street-smart, and much more.”

BLACKFASHIONCANADA.CA/JOHN WILD

For more great content like this, sign up for any of our free e-newsletters!

Cheryl Thompson is an associate professor in performance at Toronto Metropolitan University. She is the author of Uncle: Race, Nostalgia, and the Politics of Loyalty (2021) and Beauty in a Box: Detangling the Roots of Canada’s Black Beauty Culture (2019). Thompson is also director of The Laboratory for Black Creativity, a research hub for artists, academics, and dancers launched in 2022. This article was published in the February-March 2023 issue of Canada’s History.