Given that a Post Graduation Work Permit (PWGP) is non-renewable, advocates argue the program is actually limiting and cumbersome and that it causes more harm than good by pushing many international students to become undocumented and towards exploitative survival jobs.

By definition, a PGWP allows international students who have graduated from a recognized Canadian postsecondary institution to gain work experience in Canada. Students are expected to find high-skill, high-wage employment for at least one year in order to then apply for permanent residence.

“Canada’s Post Graduation Work Permit Program offers international students one of the world’s smoothest pathways to securing work in their trained field,” according to a press release from ApplyBoard, platform for international student recruitment.

However, a PGWP can be issued only once, is non-renewable, and is only granted for a minimum of eight months to a maximum of three years, “based on the length of the study program” and the applicant’s passport validity, according to the government’s website.

“Regularly scheduled breaks (for example, scheduled winter and summer breaks) should be included in the time accumulated toward the length of the post-graduation work permit,” it states. “The validity period of the post-graduation work permit may not go beyond the applicant’s passport validity date.”

Additionally, it states, PGWPs “can be extended only when the length of the permit could not be provided at the time of the application, due to the expiry date of the applicant’s passport.”

This means that if at the end of their work permit, a student is not accepted into the permanent residence pool, they effectively become undocumented.

A “setup for disaster”

At that point, they can try applying for PR under humanitarian grounds. But, as New Canadian Media previously reported, Canada has doubled its rejections of these type of applications, from 35 per cent in 2019 to 70 per cent in early 2021.

The other option to stay in the country is to apply for another study permit. But that effectively reverts them back to the 20-hour work limit with which international students have to comply. This often pushes many of them towards survival jobs that don’t count towards permanent residence requirements.

Syed Hussan, of the Migrant Workers Alliance for Change, says the non-renewable PGWPs is a “setup for disaster.”

“None of the jobs the students get to do in warehouses, in construction, retail, or gigs, count towards the PR requirements,” said Hussan during a recent virtual conference held by the organization, adding that these were “all celebrated jobs during COVID.”

Another issue, Hussan says, is the restrictive time period of the work permit, which does not give international students enough time to meet the minimum requirements for permanent residency.

According to Hussan, “even if students start a high-wage job on the first day after receiving their one-year work permit and apply for permanent residence on the last day of their job, they are still undocumented as the visa is expired.”

Having to apply for multiple study permits can also push international students to a state of anxiety and stress, says Savitri Sinanan, an international student at George Brown College.

“Have you ever considered our mental health?” she asked during the conference.

Originally from Trinidad, Sinanan shared how she has had to go through three (rejected) rounds of Canada’s Comprehensive Ranking System (CRS), which the government uses to rank immigrants in its Express Entry Pool, with the highest-ranking candidates receiving an Invitation to Apply (ITA) for permanent residence.

This has meant she’s also gone through three study permits and through around $100,000 spent since 2014 on tuition fees thus far. Her third study permit is ending this July.

“It’s the price of a luxury car in Canada and a fortune in the land where I come from,” she said, “but I certainly have not been living in luxury.”

The last time, her application was rejected citing that she has only 11 months of work experience, though she asserts she has two-and-a-half years of Canadian work experience.

“I didn’t know I had to appeal in 15 days,” she said, adding that she had no legal aid.

Sinanan said she could try for a Labour Market Impact Assessment (LMIA), which could potentially help qualify her as a foreign worker, but she says a Brampton-based consultant asked her for $45,000 to help her with the process.

“How can I afford it?” she wonders, adding that many of her jobs have paid very little, with no benefits and no paid sick leave.

“I have been abused, exploited, racially discriminated against and disrespected by employers,” she said, adding she has never taken advantage of any social assistance system and has never been a burden.

“Rather, I have contributed to early childhood education and care and have been an essential frontline worker during the pandemic.”

Sinanan, who first arrived in Canada in 2014 for an undergraduate program in early childhood education from Centennial College, says despite her excellent grades and being on the Dean’s Honour Roll, due to the 20-hour work limit, she is currently not able to find a high-wage job.

Long and arduous journey to PR

If Sinanan finally receives her permanent residence after her study permit expires in July, hers will have been an arduous, stress-filled eight-year journey.

As per Statistics Canada, Sinanan is not an outlier but one of the hundreds of thousands who will take five to 15 years or more to be granted permanent residence.

And of the international students who obtained their first study permit between 2000 and 2004, the national statistics agency reports, only 21 per cent became permanent residents within five years after the first study permit was obtained.

This proportion increased to 31 per cent when the period of observation was extended to the first 10 years after the first study permit was obtained and increased to 33 per cent by the 15th year.

Five in 10 master’s degree students and six in 10 doctoral degree students became permanent residents within 10 years of having obtained their first study permit, compared with one in three bachelor’s degree students.

The current temporary permit-to-permanent residence conversion rates corroborate the above numbers. While conversion rates of PGWP to PR could not be accessed, based on IRCC data, ApplyBoard reported that from January to October 2021, nearly 130,000 former study permit holders were approved for permanent residency.

This means hundreds of thousands of study permit holders will have to continue to wait for many more years, given that in 2019, before the pandemic, Canada had 642,480 study permit holders in the country. In 2021, 780,000 temporary residence permits were issued to current and former international students. This was nearly twice as much as the PR spots available.

According to Hussan, in 2021, when 406,000 people were approved for permanent residency, 1.1 million people were issued temporary permits — making PR a distant dream for hundreds of thousands of PGWP students. As a result, Hussan says, many students are either leaving or being forced to become undocumented.

“This is in stark contrast to Canada’s immigration system where international students are told that this is a path to permanent residency,” he says.

Crucial to the economy

Sinanan says international students should not be considered a burden to the economy. In fact, they are crucial to it.

In 2018, international students in Canada contributed an estimated $21.6 billion to Canada’s GDP and supported almost 170,000 jobs for Canada’s middle class. In addition, across Ontario’s 24 public colleges, 68 per cent of all tuition fee revenue comes from international students.

“Ontario colleges are more and more reliant on tuition revenues from international students. At some smaller schools, over 90% of their tuition fees are coming from foreign students,” confirmed Auditor General Bonnie Lysyk in a recent report.

Colleges have been recruiting more international students as domestic admissions have been reducing every year, according to that report. In fact, tuition has become colleges’ largest source of revenue in recent years, totalling $2.5 billion and surpassing the $1.9 billion available in government grants.

Yet, despite these numbers and the often-touted messaging that Canada is a very attractive place to study in, the reality many are facing stands in stark contrast.

“I came into Canada with the wrong impression,” says Sinanan. “After three years of study, and possibly two years of work experience, I thought I would become a permanent resident.”

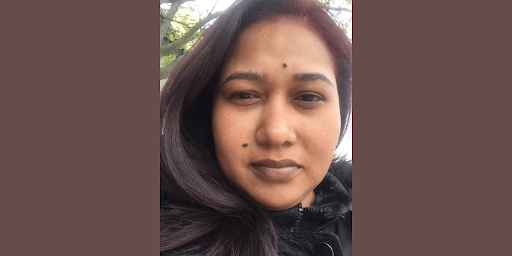

Minu Mathew is a writer and communication consultant who has worked closely with brands like Philips, 3M and Microsoft. She has a book of poems titled ‘In the Garden of Rain’ published on Amazon. Minu has lived in India, Sweden, US and UK. She currently lives in Toronto, Canada with her husband and two children.

Thanks for highlighting the real burning issues.

This is a very insightful and informative comment. Thank you to the author for sharing this information.