“No one before has shown this,” says Anthony Scimè, Associate Professor of Kinesiology and Health Science at York University, Toronto. “The unique mechanism of this protein was not expected at all!”

It is hard to miss the excitement in his voice when he talks about the research paper led by his former PhD student, Debasmita Bhattacharya, on the unique functions of a muscle stem cell protein.

The paper was published in a scientific journal called Nature Communications, creating a buzz at the university.

“Quite frankly, in my nine years at York, I cannot think of any other student or professor who was published in the Nature journals,” he explains. Of over 500 research submissions every year, only 7.7 per cent are accepted for publishing, after rigorous peer-review.’

Bhattacharya’s thesis has been nominated by York University for the Faculty of Graduate Studies award where three winners will be selected among the top theses university-wide on June 6. Bhattacharya explains the significance of her research.

Scimè talks about Bhattacharya’s journey and the implications of her research (Video: Joyeeta Ray)

Big discovery on a little-known protein

“There are thousands of proteins in the body of which the p107 is one. How this protein functions within the cell has never been researched,” explains Bhattacharya.

“The paper examines how the p107 protein influences proliferation (rapid growth) of muscle stem cells. This could lead to a new understanding which could have implications in the treatment of hard-to-treat ailments such as cancer, muscle dystrophy, and age-related muscle disorders,” she says.

“Cancer cells [damaged cells] proliferate very rapidly. If we can control the proliferation of cancer cells, it could have therapeutic implications in the future,” she explains.

It has taken Bhattacharya eight years at the lab, working in quiet isolation away from her husband and daughter, to complete both her Master’s and PhD to arrive here.

Rejection despite high education

Bhattacharya was 26 when she and her two-year-old daughter moved to Brampton with her husband from Kolkata, India, about 10 years back.

Her husband Baishampayan, 32, gave up a flourishing medical career as an ENT specialist to move to Canada in the hope of a better life for the family.

Armed with high qualifications and experience, he was confident about finding a job as a healthcare practitioner. So he encouraged his wife to complete higher education, well aware of her academic potential.

Unfortunately, things didn’t turn out as they expected. Bhattacharya was rejected from the Master’s program despite excelling in her Bachelor’s in Bioengineering back in India.

“It is not unusual to be rejected from a Master’s or PhD program in Canada if one is refused by a supervisor,” Bhattacharya says. But the grounds for her rejection left her unprepared.

“The supervisor asked me over an email if I had a family with me in Canada. On hearing that I had a husband and two-year-old daughter, my application was rejected. She said that a child would distract me from giving the program the full commitment it demanded,” says Bhattacharya.

She was distraught but did not lose hope. She reached out to Anthony Scimè, who welcomed her into the program, understanding her situation. But her hurdles did not end there.

There were no fixed hours at the lab. “Once I entered, I had no clue when I would be home.” As a result, she could barely spend time with her family even on weekends. Her husband was hit hard too.

Devaluing foreign experience

“My husband could not land a job in the medical field despite being a licensed doctor from back home,” says Bhattacharya.

“In Canada, foreign-trained medical professionals need to go through an accreditation process. Although he started the program, he gave it up mid-way to work as a lab technician to meet financial needs.” He gave that up too in frustration, feeling overqualified and disinterested in the job.

“Had he known that his medical expertise would not land him a job [in his chosen profession] here, we may not have come here at all!” Bhattacharya admits.

Left with no option, Baishampayan took the difficult decision to switch to finance. The brokerage he was associated with allowed him the flexibility to work from home when required.

The gamble paid off. After an initial struggle he did well, and Bhattacharya was able to focus on her research, relieved that her husband was home to look after their daughter.

However, when his finance venture took off, he gave up his medical career for good.

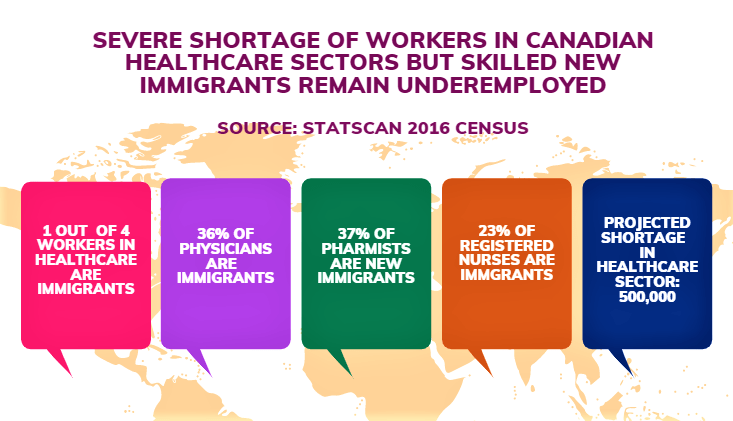

Devaluing foreign experience has created critical shortage in frontline workers and medical equipment for Canada, straining the healthcare system during the covid 19 pandemic.

Only 41 per cent of internationally educated healthcare professionals are employed in their fields compared to 58 per cent of Canadian-born professionals.

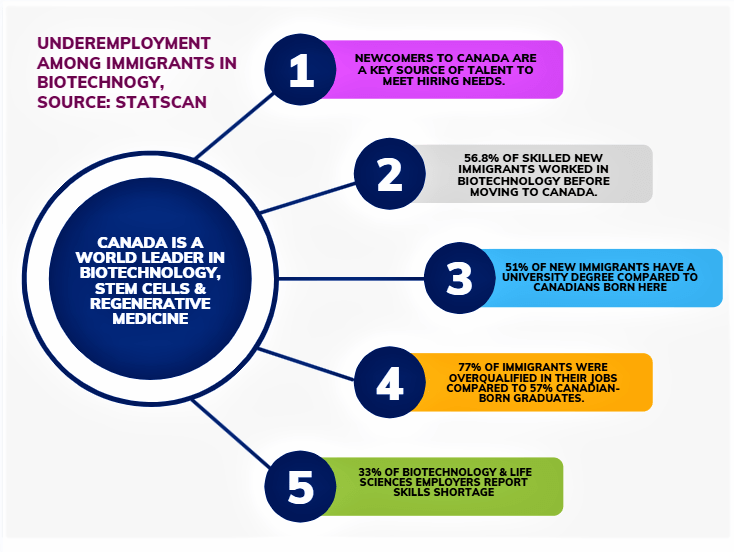

In biotechnology, a lack of capital fails to attract and retain candidates, both in higher education programs and the workforce.

“I invested eight years of my life earning just $22,000 annually from PhD funds,” confesses Bhattacharya, most of which was received through government grants.

“My funds were less than what I was spending on daycare,” she says, explaining why few newcomers with a family find it hard to pursue PhD programs. It is difficult for them to support a family.”

Bhattacharya now teaches at Humber College while pursuing a postdoctoral fellowship at York University under another professor. Scimè has moved on with a different team to follow up on Bhattacharya’s research. But he is excited about what Bhattacharya started.

“Usually, research of this magnitude is conducted by several laboratories. We are a small team of four people with limited resources. So, the hard work of Deb and others in the lab, Vicky Shaw, Oreoluwa Oresajo and I paid off,” he says.

“The importance here is that we discovered the way adult muscle cells divide by a new mechanism which applies in other cell types like cancer cells. We discovered a way to stop the proliferation of cancer cells. We are following this up in the lab.”

“Her research is exciting because of the mechanism that she discovered. This is a major discovery,” says Scimè.

After years of working in isolation, Bhattacharya feels her hard work has paid off. “When you receive appreciation from eminent scientists in international conferences across Canada, you begin to realize the real effectiveness of your work,” she says with a smile.

While Bhattacharya impatiently waits for the awards process to know the outcome of her nominations, she has unfinished business left on her wish list. “I would like to meet the professor who rejected my Master’s application and let her know about my research paper,” she says. “No woman should be discouraged from pursuing higher education simply because she is a mother!” she asserts.

Collective Convenor & Communications Planner - Joyeeta Ray is a multimedia journalist, internationally awarded digital content specialist, and children’s books author, based in Toronto. Born in India, she brings over two decades of advertising and journalism experience across seven countries to Canada. Joyeeta started her journalistic career in Jakarta, led an editorial team in Bangkok, and is a student of Multimedia Journalism from The University of Toronto. She is an enthusiastic NCM-CAJ member, actively involved in amplifying new Canadian voices as NCM’s Convenor, Communications Planner, Mentor, and Reporter.