Hardi Darwesh was just five years old when, by a stroke of fortune, his family managed to flee the Kurdish area in northern Iraq where Iraqi intelligence officers would kill thousands of men while taking the women and girls.

“In the evening, I was playing with my friends when a vehicle brought back some dead bodies. Everyone screamed and immediately left and escaped all night,” he told New Canadian Media.

Darwesh is one of the few who escaped the Anfal campaign — also known as the Anfal genocide — that Saddam Hussein, Iraq’s former president, ordered on the north of the country 34 years ago. The attacks lasted from Feb. 23 until Sept. 6, 1988, with up to 182,000 civilians killed or disappeared, and 90 per cent of the villages looted and ravaged in the Garmian Region in northern Iraq.

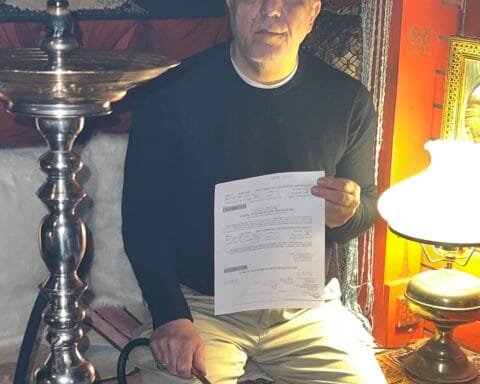

Today, Darwesh is a Canadian citizen living in Vancouver, British Columbia, thousands of miles away from the country in which he was born.

But the memories of the events still traumatize and haunt him, giving him nightmares for years, he says, as ongoing wars robbed him of his childhood forever.

“I think we all need psychological treatment to alleviate our pain and trauma,” he says, adding that he can still hear the screams of women and girls, and the sounds of warplanes and military vehicles still echo in his mind.

According to Britannica, genocide is defined as: “The deliberate and systematic destruction of a group of people because of their ethnicity, nationality, religion, or race.” By 2007, the Supreme Iraqi Criminal Tribunal decided the definition fit and ruled Anfal to have been a genocide against the Kurds.

According to the 2016 census, there are 16,315 Kurds living in Canada who’ve immigrated from Iraq, Iran, Syria and Turkey. But the Canadian government has refused to recognize Anfal as a genocide, despite calls from the diaspora to do so.

That’s partly why 34 years later, Kurds in Canada continue expressing worry about another such attack. And as the situation deteriorates in Iraq, with civilian anger increasing over unpaid salaries, unemployment and a lack of basic services, with neither the Iraqi nor the Iraqi-Kurdish governments providing support, many feel they are being left to fend for themselves.

With recently reported threats against Kurdistan from neighbouring countries like Turkey and Iran, Darwesh says he fears history might be repeating itself.

Not so much fear but anger

In 2010, three years after the official recognition of Anfal as a genocide, the Supreme Iraqi Criminal Tribunal issued arrest warrants for 258 accused Kurdish Mustashars (collaborators) for their involvement during the Anfal campaign and sent the warrants to the relevant authorities in the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG).

To date, neither the Iraqi government nor the KRG have taken any action.

Khaled Sulaiman, a Montreal-based environmental journalist, came to Canada several years ago with his family from the town of Kalar, in the west of the Sulaymaniyah Governorate, at the epicentre of the Anfal genocide.

For him, the possibility of another Anfal evokes not so much fear but anger towards the local Kurdish authorities for what he sees as their inaction.

“Partisan, regional and individual interests have dominated the interest of the Kurdish people. The rulers in Kurdistan have become billionaires as a result of corruption and misuse of power, while the families of the Anfal victims live in poverty and destitution,” he says.

Another reason why people are furious with the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG) is that the two main parties, the Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP) and the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (PUK), have opted to protect former collaborators and advisors who aided the Ba‘ath regime during the genocide.

International community’s duplicity

Like Canada, the international community has also not recognized the genocide, as it has with other genocides such as the Holocaust. This, says Sulaiman, also put Kurds at further risk by silencing the killings of tens of thousands of Kurdish women, children and men at the hands of Hussein’s regime.

“In view of their interests with the countries occupying Kurdistan, the international actors consider the Kurdish issue only as a card that can be used at the appropriate time,” he says.

“Today, we see how Turkey practises a similar policy against the Kurds … and no one says ‘no’ to (President Recep Tayyip) Erdogan’s politics against the Kurds … It is absolute hypocrisy and duplicity.”

Darwesh says if the Canadian government recognized the genocide, it would be a big step towards compelling the international community to act to expand the protection of local human rights.

Misusing the term

The term Al-Anfal is the name of the eighth Sura (chapter) of the Quran, meaning “The Spoils of War,” and it’s used in the Quran to refer to the clash between the Meccan disbelievers and Muslims in the battle of Badr in 624 AD.

According to the Quran, the Muslims won that war and God told the Muslim prophet Muhammad, “The booty is in fact a bounty from God thus they should be mindful of Him and obey Him.”

However, Ba’ath authorities, who have traditionally held socialist leanings, have misused the term to claim they were quelling a rebellion ignited by Kurds who sided with the enemy during the eight-year Iran-Iraq war from 1980-88.

But the Kurd’s crime was simply being Kurds in Iraq. According to a 2004 Human Rights Watch report, since 1975 the former Iraqi government engaged in a policy known as “Arabization” which saw “hundreds of thousands of Kurds, Turkomans, and Assyrians (displaced) from their homes” and replaced with “Arab settlers.”

“Although the aims of the Anfal campaign was not Arabization — the aim was genocide — in its aftermath Kurds were not allowed to return to their destroyed villages,” the report elaborates. “Their property rights, too, were invalidated, and Arabs were brought to settle and farm some of their lands.”

Never forgetting

Three years after the Anfal genocide, the Kurds overthrew Hussein’s regime in Kurdistan and elected their own, independent government, enabling the people, full of hope and expectation, to return to their ravaged villages and towns.

Their dreams and hopes came to fruition when the Kurdish authorities declared an amnesty for all who collaborated on the overthrow.

But they failed to give the families of the victims a pension for what they’d endured or to help them rebuild their houses and lives.

Sulaiman, who lost some of his relatives during Anfal, says though the memories are painful, he carries them with him everywhere, to never forget the attempted genocide of his people.

“I miss my family members more — my uncles, their wives and children, and childhood friends,” he says. “Whenever I remember Anfal, I invoke the souls of my loved ones. Their pictures accompany me wherever I am, in Montreal or in Kurdistan.”

Diary Marif is a Vancouver-based Kurdish writer and award-winning journalist born in Iraq. He holds a master’s degree in history from Pune University in India (2013). His journalism has appeared in national and international outlets, including Rabble, Canadian Dimension, CBC Arts, Culturico, The Amargi, and The Canadian Encyclopedia. Since 2018, Marif has centred his creative work on memoir and personal narrative, exploring his experiences as a child of war. He has written chapter books for multiple projects and has appeared as a storyteller in public spaces. He received an Honourable Mention for the 2022 Susan Crean Award for Nonfiction, is a 2025 recipient of the Yosef Wosk Vancouver Manuscript Intensive Fellowship, and was awarded PEN Canada’s 2025 Marie-Ange Garrigue Prize.