Canada’s non-permanent residents, including temporary foreign workers, international students, and asylum seekers, have fought many existential battles during the COVID-19 pandemic — not only to stay healthy but also just to stay in the country, make a living, and access health care and government support. Coverage of these struggles in ethnic media has also laid bare such systemic problems like exploitation of migrant workers and the dependence of many sectors on migrant labour.

In their reporting on migrants in Canada, many outlets relied on statements coming from NGOs and non-profits, and thus amplified their messages. Extensively reported were calls from various advocacy groups (and rallies held across Canada) demanding permanent residency for foreign care workers, farm workers, international students, and irregular-status immigrants who have continued to work on the front lines of the COVID-19 pandemic.

One of the most often cited NGOs was the Migrant Workers Alliance for Change, which argued that the lack of protection and rights that permanent residents enjoy has enabled abusive situations in which temporary workers were not allowed to leave their residences, while those who got sick were not able to access health care.

- Overview of ethnic media analysis

- Mainstream media analysis

- Word from our partner, MIREMS

- Commentary from the NCM Collective

Foreign workers face a lack of safe conditions, abuse and exploitation

Temporary foreign workers and undocumented migrants have been one of the most affected groups during the pandemic, as covered by ethnic media from May to December. “The fact that in 2020, people are dying on farms in Ontario in one of the richest and most socially and technologically advanced countries in the world, Canada, is truly cause for reflection,” an Italian outlet wrote in early July, after multiple reports of COVID-19 outbreaks at farms employing seasonal workers from Latin America and the Caribbean, and deaths of three Mexican workers.

Outlets carried stories by migrants who said they were forced to start working right after arrival (without the 14-day quarantine) or had to quarantine in rooms that had no food or inadequate space to allow for physical distancing. The Migrant Workers Alliance for Change was cited as saying that it had received complaints from more than 1,000 people that their working and living conditions were crowded, they were unable to maintain the two-metre distance and lacked personal protection supplies.

One of the prominent cases was that of a Mexican farm worker, Gabriel Flores, who won compensation from his employer, Scotlynn Farms, in front of the Ontario Labour Relations Board. Flores sued Scotlynn Farms after he had been fired for speaking to the media about insufficient protection at the facility, where almost 200 workers had gotten infected with COVID-19.

Live-in care workers were shown to be highly vulnerable as well. A lot of media attention was devoted to a report titled “Behind Closed Doors: Exposing Migrant Care Worker Exploitation During COVID-19,” based on a survey of 201 migrant care workers and released in late October. The report showed that nearly half of the respondents were forced to work longer hours without being paid overtime. Two out of three workers said they weren’t allowed to leave the house, send money back home or even go to the doctor for fearing of breaking family quarantine bubbles.

What clearly transpired in ethnic media coverage was the fact that temporary foreign workers are the backbone of Canada’s food supply and many other essential sectors, but they are not getting basic rights protection.

In fact, as one Filipino outlet observed, Canada has depended on “cheap immigrant labour” from “Chinese railway workers to the Japanese fishermen, to South Asian farmers and loggers, to the Filipino overseas workers.”

Domestic work, health care and hospitality are all sectors that “capitalize on cheap female labour from the Global South,” wrote another, reporting a story of a Filipino woman who was separated from her son for five years as she was working in Kelowna, B.C., as a housekeeper at a hotel and as sanitation staff at a hospital. The pandemic has cost her and her husband their jobs at the hotel, and she still owes a substantial sum to an immigration agency.

“Guardian angels” of Quebec get pathway to permanent residency

Substantial coverage was given to the precarious status of many asylum seekers working or volunteering at long-term senior care homes and in other health-care settings in Quebec, including the price they have paid with their health.

These workers, whom Quebec Premier François Legault called “guardian angels,” are largely Haitians who came to Canada irregularly from the U.S. According to Montreal’s Haitian community advocate Ruth Pierre-Paul, cited in Caribbean media, hundreds of them have sought out jobs in long-term care homes as a quick way to enter the workforce.

After weeks of advocacy, media attention and petitions to the federal government, in August, Immigration Minister Marco Mendicino announced a pathway to permanent residency for asylum claimants working in health care during the pandemic. Several media outlets praised the move, but many also stressed that the program is closed to asylum seekers doing other essential jobs. This has left many people disappointed and triggered further protests.

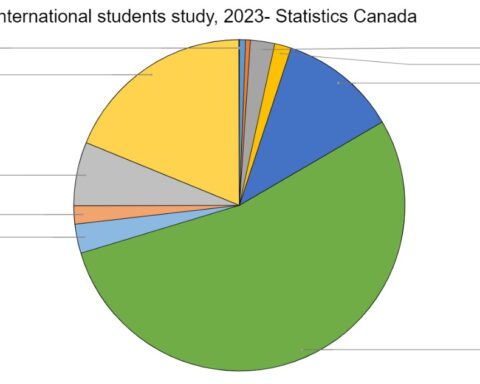

International students treated like “cash cows”

International students have faced a lot of uncertainty, anxiety and financial pressure in the pandemic months, and ethnic media have covered these struggles closely. As reported, the main dilemma faced by students before the start of the new academic year was whether to attempt entering Canada at the risk of being turned back at the border (which happened to many) or stay in their home countries and study online.

Until October 20, only individuals with study permits issued before March 18 were able to travel to Canada, and solely for a “non-discretionary or non-optional purpose.” Other students were subject to a travel ban.

For students from China and India, who account for the bulk of international students in Canada, attending university online in their home countries has meant having to study at odd hours and cope with internet issues. As reported, students also missed exposure to local culture, which they thought might later affect their chances on the job market. Some consolation came with a July announcement that time spent studying online abroad would be counted toward a post-graduation work permit.

There has been no relief in terms of cost, however. Universities not only refused to give rebates to those studying online; some have even raised tuition fees for foreign students, prompting comments in ethnic media that international students were treated like “cash cows” by “shameless Canadian universities.”

International students already in Canada also struggled. According to Chinese outlets, many Chinese students decided to stay in the country despite classes going online, mostly because the flights were very expensive and hard to come by. They also did not want to risk being stranded back home. But with high costs of living, few summer job opportunities, almost no help from the federal government, and no social activities, students were reported to be feeling helpless, frustrated, anxious and homesick.

Punjabi broadcast media noted that many students were under pressure to find work to support themselves and send money back to their families. Concerns were also expressed over “suicidal incidents among international students.”

Non-permanent residents in mainstream media coverage

Similar to the coverage offered in ethnic media, coverage by Toronto Star broadly reflected two major perspectives—conveying government policy and programs and also offering human interest stories reflecting the lived experiences of the newcomers, migrant workers, refugees and international students.

The paper quite extensively explored how immigrants and newcomers to Canada have been affected by COVID-19 pandemic from the economic, social and health and well-being angles. Dozens of articles addressed the issue of temporary farm workers, highlighting their precarious situation as well as legal battles. Solid coverage was also devoted to refugees and asylum seekers and the processes related to their status, brought to readers’ attention via a number of human-interest stories.

The issues facing international students, whether stranded in Canada or overseas, also received attention. Among others, the Star carried discussion regarding tuition fees and opportunities for foreign students to change their status.

Among the Postmedia Network titles, the Windsor Star appeared to carry the most coverage relating to migrants and the pandemic — perhaps unsurprisingly, given that more than half of the local COVID-19- cases during the pandemic’s first wave were among the thousands of migrant workers employed in the agri-food sector in Southwestern Ontario’s Essex County.

Another significant aspect of the coverage was the call on the government to create a new permanent residency program for migrant workers, including undocumented workers, in sectors facing labour shortages. Advocates were asking the government to allow migrant farm workers to apply for a 12-month open work permit that would maintain or regularize their status while their application for permanent residency was in process.

Insight from MIREMS media monitoring

“Ethnic media has been instrumental in reporting on and clarifying government policy, processes and programs. It has also documented the unique challenges different migrant constituencies face and has been part of successful lobbying efforts for concrete solutions,” summed up Silke Reichrath, Editor-in-Chief at MIREMS.

Of particular concern were temporary foreign workers, international students, asylum seekers, and undocumented workers.

In terms of immigration policy, a lot of coverage was devoted to the impact of COVID on immigration levels, border closures and travel restrictions, visa extensions for temporary residents stranded in Canada, work permit regulations, farm worker rights and COVID safety protocols, COVID-related accommodations for international students, modifications to the Express Entry draws, and the “guardian angel” program for front-line care providers. Ethnic media frequently aired interviews with immigration lawyers and consultants as well as with lawmakers.

Another concern reflected in the ethnic media has been around family reunification. The processing of spousal sponsorship cases has stalled, and ethnic media has reported repeatedly on protests organized to ask the government to resume processing sponsorships.

Methodology: This ethnic media analysis is based on a selection of 350 summaries of articles and broadcast segments in radio, TV, print and web sources between May and December, 2020. These summaries were selected from about 6,000 items on these issues found in 450 active ethnic media sources in Canada monitored by MIREMS.

For mainstream media analysis, the ProQuest Databases Platform was searched using such keywords as “newcomers,” “immigrants,” “international students,” “refugees,” and “COVID-19.” The search yielded 124 articles published by Toronto Star over the period July 1–Dec 31, 2020. Postmedia articles published over the last 12 months were searched separately using the keywords “migrants” and “pandemic,” and then analyzed using Natural Language Processing.

Commentary from the NCM Collective

Tunde Asaju (Nigerian): News that Canada had bought more vaccines than its burgeoning population required jolted many immigrant Africans. Immigrants always have to look out for relatives at home. The continent often does not have the wherewithal to get vaccines when needed. These fears were allayed when Prime Minister Justin Trudeau announced in a CFRA interview that Canada would play big brother to poorer nations.

The next worry is the news that Canada would request a negative COVID-19 test result from international travellers. Immigrants who travelled out during the Yuletide season are waiting patiently for details of the new modalities from the Canadian government.

Christopher Chanco (Filipino): Throughout the pandemic, coverage in the Filipino-Canadian press has highlighted its economic impacts on the diaspora, even as it has stressed Canada’s reliance on Filipino frontliners in the health-care sector. In Alberta, some Filipino workers have been left stranded by the provincial government’s decision to stop hiring temporary foreign workers to prioritize citizens in key sectors like retail and construction. News coverage has mentioned the participation of Filipino migrant rights advocates in campaigns to provide amnesty for undocumented workers.

Filipino-Canadian journalists also pointed to delays in the processing of permanent residency and family reunification applications. The Philippines remains the top third source-country for immigrants to Canada. Pandemic-related border restrictions have, however, seen the numbers of immigrants admitted falling well below immigration targets in 2020. One outlet has covered the Canadian government’s commitment to prioritize immigration through family reunification in its post-pandemic economic recovery programme. Filipinos have notably expressed hopes of accelerating the processing of family sponsorship applications to increase admissions for parents and grandparents.

Shalaw Fatah (Arabic): While coverage of COVID-19 has dominated Arabic outlets in Canada for months, there was very little about how it is affecting minority communities. Recently, most publications noted the increase in COVID-19 cases, especially in Quebec and Ontario. Some outlets reported on other consequences related to the pandemic, like halting 200 international flights in mid-December.

Shalaw Fatah (Arabic): While coverage of COVID-19 has dominated Arabic outlets in Canada for months, there was very little about how it is affecting minority communities. Recently, most publications noted the increase in COVID-19 cases, especially in Quebec and Ontario. Some outlets reported on other consequences related to the pandemic, like halting 200 international flights in mid-December.

Tazeen Inam (Urdu): Besides Urdu ethnic media, social media, particularly Facebook, became a vital source of information for the community. Most popular are women-led groups. Students and their parents from Pakistan joined these groups to share their concerns and seek advice on international travel restrictions, particularly for students who were scheduled to arrive in 2020. Though universities and colleges resumed online, the challenge was greater for Pakistani students in terms of the time difference and fees, which remained the same at a time when the students were unable to do part-time jobs in Canada. There are growing concerns about post-university work permits being affected. New students are facing delays of approximately five to six months for study permits, despite admission approval from universities.

Isabel Inclan (Hispanic): Hispanic media continue covering the pandemic informing their readers about the increase of cases in Canada, the vaccines, and the new regulations for socializing and doing business. Some Spanish-speaking media have dedicated space to cover the negative impact of the COVID-19 in the farms, especially in the south of Ontario, where thousands of farmworkers were infected and three of them died.

Although international students from Latin American countries, such as Mexico, Chile, Argentina and Colombia, are an important part of foreign students who come to Canada each year, Hispanic media have overlooked reporting on the situation of international students whose work permits could not be renewed and who face a precarious immigration status. This was denounced by the Migrant Workers Alliance last November but wasn’t reflected in the Spanish news (Toronto media).

Marcus Medford (Caribbean):

The main themes I’ve encountered reading Caribbean-Canadian publications were migrant workers’ fight for more rights, reminders to appreciate the contributions of migrant workers, and the poor conditions they’re often subject to. The migrant workers were usually working on farms and not as personal support workers.

Migrant workers have fought to be recognized as permanent residents in order to access the government’s financial support programs. Also, because of their vulnerable immigration status, some migrant workers feared getting tested for COVID-19 because a positive result could lead to their termination or deportation. Some publications mentioned that migrant workers should be seen as essential workers, especially during the pandemic, and deserve higher wages, better work protections, and safer working conditions.

One article argued that Canada’s ‘two-tiered immigration system’ is an example of systemic racism as it denies some residents certain rights and allows for them to be treated poorly. In two articles I read, one in Toronto Caribbean Newspaper and the other in The Caribbean Camera, as well as in interviews featured on CBC’s The Current, people have compared the conditions of migrant workers to those of slaves.

Shan Qiao (Chinese): Mandarin Chinese media outlets have recently been focusing on heated debates about who does a better job in dealing with the global pandemic: China or the western world? This has ranged from wearing masks during early stages of the outbreak to the dramatic quarantine China enforced, to China’s tightened travel restrictions, to the choice between China’s and Western versions of the vaccines. This echoes the lingering conflicts between Beijing and the Western world on human rights, values and individual choice.

Pradip Rodrigues (South Asian): There was mention about multi-generational living as being a concern and a fact of life in South Asian communities, but very little about the unknown number of rooming houses filled with half-a-dozen or more international students, most working as frontline workers and living in crowded dwellings. The media has largely avoided digging deeper into this very serious issue.

Arpan Chahal (Punjabi): The South Asian community has been a scapegoat in the blame game of high infection rates in places like Vancouver, Surrey, Calgary and Brampton, which also have concentrations of immigrants from the Indian state of Punjab.

Arpan Chahal (Punjabi): The South Asian community has been a scapegoat in the blame game of high infection rates in places like Vancouver, Surrey, Calgary and Brampton, which also have concentrations of immigrants from the Indian state of Punjab.

Ever since the direct attack by Alberta Premier Jason Kenney on a Red FM radio talk show, in which he bluntly accused the community of organizing large gatherings, showing no respect for the province’s health guidelines and blaming the ‘joint family’ living arrangements as one of the factors leading to a high case count in Calgary, the Punjabi media have risen as one against this sort of stereotyping. Rishi Nagar, a member of the Calgary Anti-Racism Action Committee, was one of the first people to ask for an open apology against such comments. Similar comments by public figures against the Punjabi community resulted in a backlash in Brampton, including from NDP leaders.

Punjabi broadcast and print media have been doing an excellent job in providing their audiences with information about the vaccine and the misconceptions surrounding it, travel rules and provincial health guidelines, hosting several talk shows with local authorities and leaders, while at the same time trying not to pit one community against another.

Vladimir Umnov (Russian): Many Russian-speaking media and social media write that newcomers worry about cancelled citizenship tests. They are waiting for when tests will be re-open. Unfortunately, immigration officials don’t say much about this problem. Moreover, when the government explained that the number of staff decreased, people didn’t understand why because Canadians have not heard about anybody from the public service that lost their jobs as a result of the pandemic. Additionally, many newcomers worry about expired PR cards. Some of them sent documents to update the PR card, but there has not been any answer in the last few months. As a result, Russian-speaking media and social media are very pessimistic about immigration services.

Vladimir Umnov (Russian): Many Russian-speaking media and social media write that newcomers worry about cancelled citizenship tests. They are waiting for when tests will be re-open. Unfortunately, immigration officials don’t say much about this problem. Moreover, when the government explained that the number of staff decreased, people didn’t understand why because Canadians have not heard about anybody from the public service that lost their jobs as a result of the pandemic. Additionally, many newcomers worry about expired PR cards. Some of them sent documents to update the PR card, but there has not been any answer in the last few months. As a result, Russian-speaking media and social media are very pessimistic about immigration services.

This NCM media analysis has been produced with funding support from the Digital Citizen Contribution Program.

Read Part 1: COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy Amplified by Small Section of Ethnic Media

Read Part 2: Unsung Heroes or Super Spreaders: Racial and Ethnic Minorities in COVID-19 Coverage

Alicja Minda is an NCM journalist, editor and researcher with extensive experience covering business and economy as well as global affairs. She has worked as Canada correspondent for the Polish Press Agency. In her free time, she is volunteering with Editors Canada as editor-in-chief of the Editors Toronto official blog, BoldFace.

Naser Miftari is an independent media researcher. His broad area of interest is in political theory and his research focus is on the future of public broadcasting, media governance and political economy of communication. For more than ten years he was a writer and editor for Koha Ditore one of leading newspapers in South East Europe. He is an active contributor in media research studies and has also taught graduate and undergraduate courses in media and political science at colleges and universities in United States and South East Europe. More recently he served as a contributor on global journalism issues with the Toronto-based Canadian Journalists for Freedom of Expression (CJFE) and in 2016 he was a research fellow at King’s College in New York.