The advocacy group No One Is Illegal – Nova Scotia (NOII-NS) has launched a poster campaign to draw attention to the plight of temporary foreign farm workers, saying that many have worked in the province for decades and should be granted permanent resident status.

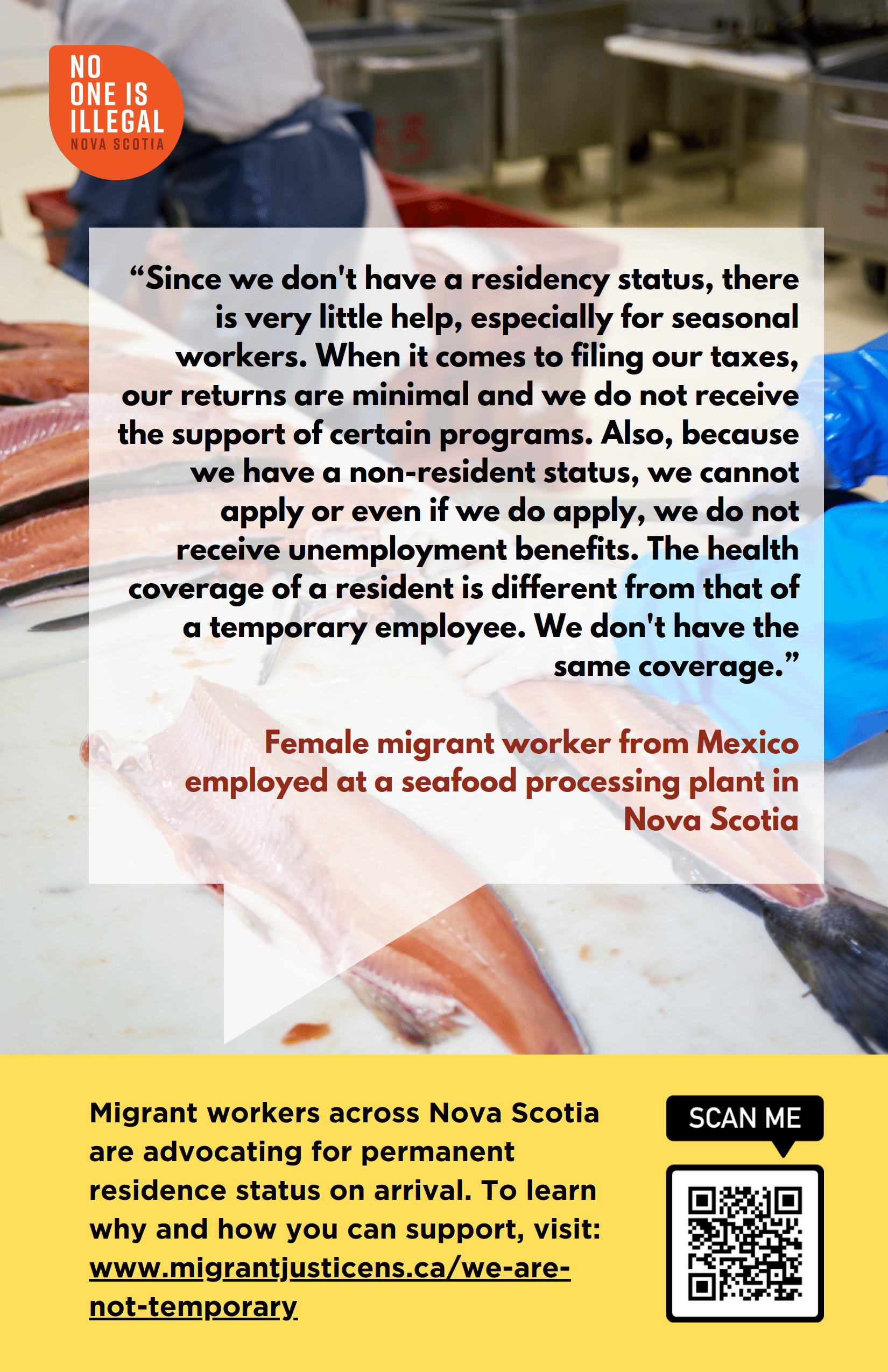

The “We are not temporary” poster campaign, which highlights the voices of migrant workers in Nova Scotia, was launched in Halifax on November 25th and will continue until Dec. 10 — Human Rights Day.

“We frame this campaign on Human Rights Day because there is an abuse of the rights of migrant workers. Their human or labour rights are not being respected,” said Stacey Gomez, manager of the NOII-NS migrant worker program. “We found that this is a systematic problem.”

The posters are being distributed in markets, community centers and on the streets of Halifax, New Glasgow, Bridgewater, and Wolfville.

This fall, the advocacy group conducted a survey of temporary farm workers in the agriculture, seafood and food service sectors in Nova Scotia.

The majority of the 141 respondents (99 per cent) indicated that they favour permanent residence status for all temporary migrant workers because many of them have worked in Canada for more than 10 years.

Farm workers are vulnerable because they are tied to one employer each season, Gomez says.

New Canadian Media interviewed one of the survey respondents, a temporary farm worker from Mexico. Because he fears reprisals from his employer, NCM has agreed not to use his name, and instead refer to him as González.

In the last two decades, González has worked at farms in Simcoe, Niagara, Vancouver and Halifax areas, harvesting tons of broccoli, cabbage, grapes and kale, among other vegetables.

González is a father of five children and wants to become a permanent resident so he can collect retirement benefits and bring his youngest daughter to Canada to study.

“If I retired in Canada I would have full pension,” said González, who says he makes $15 per hour.

“I deserve permanent residence for all the years I have worked in Canada.

“I have the right to a full and decent pension because I have earned it hard,” the 54-year-old worker said, adding that “when my employer asks me to work more hours, I always comply.”

In 2022, an estimated 3,360 migrant workers were living and working in Nova Scotia, of which 1,649 were employed in the agriculture sector, which was 13 per cent more than in 2019, according to Statistics Canada.

Gomez stressed that migrant workers face significant labour issues in Canada.

“Migrant workers pay taxes but do not have public health coverage. They pay for Employment Insurance, but they are generally not able to access it. They are tied to a single employer, which puts them in a vulnerable situation.”

In Nova Scotia, most migrant workers don’t have access to Medical Services Insurance (MSI) because coverage begins after 12 months, but the contracts of Seasonal Agricultural Workers range from three to eight months. In Ontario and Quebec, seasonal agricultural workers are covered by public health upon arrival.

González recalled the day he had a hand injury while cutting vegetables. “The supervisor told me that there was no one to take me to the hospital, that I should go by myself,” he said.

The NOII-NS survey polled 141 migrant workers in the agriculture, restaurant, hospitality and fishing sectors. Originally from Mexico, Guatemala, Jamaica, and St. Lucia, they have been coming to work in Canada between eight and 30 years.

Full survey results will be officially released soon, but Gomez said 30 per cent of the responders said family separation is one of the reasons they want permanent residence.

Some workers (20 per cent) said getting permanent residence status would improve their general working conditions and give them the right to access to benefits such as unemployment insurance, health-care services, Gomez explained.

In her survey response, a female migrant farm worker from Jamaica stated: “As migrant workers in Canada, we are excluded from many benefits such as basic health care. Also, we are given closed work permits tying us to employers. We have to live with how they treat us. We are afraid of talking because our family depends on us, and we don’t want to face deportation.”

This story was produced in partnership between SaltWire and New Canadian Media.

Isabel Inclan has worked as a journalist for more than 20 years, in both Mexico and Canada. She began working as a foreign correspondent in Canada in 1999 for Mexican media. She has been a New Canadian Media contributor since 2018. Her main areas of interest are politics, migration, women, community, and cultural issues. In 2015, Isabel was honoured as one of the “10 most influential Hispanic Canadians.” She is a graduate of Masters in Communication and Culture at TMU-York University. She is a member of CAJ and a member of the BEMC´s Advisory Committee.