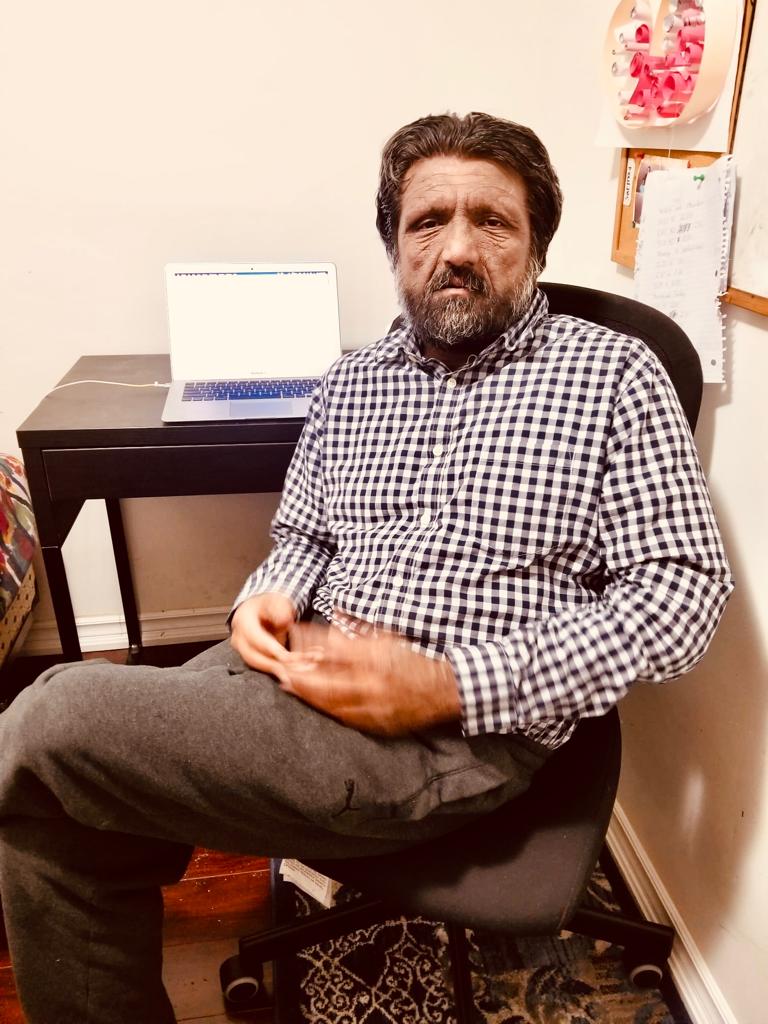

After being tortured for 21 days in Pakistan, blogger and poet Salman Haider finally feels at ease in Canada — at least enough to share the saga that got him here, a place with noticeable press freedom compared to Pakistan.

“There’s a lot more freedom here when it comes to writing focusing on minorities, Indigenous communities and religious freedom,” Haider tells New Canadian Media.

But while he finds there is ample coverage of and “condemnation by different levels of leadership” against domestic racism and hate crimes, he says there is a lack of coverage of events happening in developing countries like his native Pakistan.

“Canada is a torchbearer for human rights, but we do not see media coverage on atrocities happening (elsewhere in the world),” he says.

He believes that “Canadian media can play a vital role in human rights issues by promoting its values and supporting causes outside Canada.”

While he has limited access to news in Canada due to paywall restrictions, he says he still keenly follows human rights developments around the world.

Human rights activism in Pakistan

As a psychology professor in Islamabad, Haider championed minority rights and religious freedoms.

He was especially critical of the enforced disappearances of civilians in Balochistan – a southwestern province in Pakistan bordering Afghanistan and Iran, and the epicentre of a decades-long separatist movement allegedly backed by India.

As a columnist, Haider regularly published political satire for a national daily in Pakistan. He was also an editor for the progressive journal called Tanqeed, or “Criticism,” which focuses on religious and ethnic minority rights.

He says the journal covered and criticized the army, including their support for the Taliban, as well as the way the media covered these issues.

Haider and four other activists co-founded a Facebook page titled “Mochi,” which translates as “cobbler,” where they campaigned for human rights and religious freedoms. Their satirical posts and poetry exposed human rights violations committed by security forces and religious extremists who “have historically been connected with the army,” says Haider.

“The term was used for the journalists who were supporting the army in the media, or the politicians who were supporting or who were being supported by the army,” he explains.

This, he believes, “is what initiated their persecution.”

Death threats and abduction

In January 2017, Haider was kidnapped in Islamabad along with his fellow activists.

The government of Pakistan denied accusations that its secret militant agencies were involved in the abduction.

In the months leading up to the kidnapping, Haider had received a slew of abusive comments and death threats on social media, unknown calls and messages with racial slurs and accusations of blasphemy, which is a crime in Pakistan.

The Federal Investigation Agency of Pakistan ordered an investigation of Haider, and he was banned from leaving the country until it was completed, though eventually police found no evidence of this.

Pakistan is caught in a vicious circle of debates over blasphemy, minority rights and religious freedoms, with the nation and authorities divided over the issues.

Haider says hundreds of people including university professors, human rights activists and poets from across Pakistan had come out on the streets to demand that the authorities release the bloggers.

“Human rights associations and the people I worked with came forward and started protesting,” Haider says, adding that the protests were noticed worldwide, with the White House issuing a statement for the safe return of the activists.

“It was discussed at the UN, and Amnesty International came forward to rescue (all the activists),” Haider says. “I was released after 21 days.”

Though leading religious scholars condemn such atrocities, in 2011 the government sentenced to death a guard who had killed a former governor of Punjab over allegations of blasphemy.

For his part, Haider suggests “strong federating units” to limit Pakistan’s central government’s powers, as well as “taxing the corporate empire, run in the name of army welfare, and cutting down the non-combatant expenditures of the army.”

He also opposes state support available to terrorist organizations, which he says “are oppressing religious and ethnic minorities.”

Journey to North America

Before his abduction, Haider had applied for a fellowship at the University of Texas, where he arrived after U.S. authorities expedited his visa process.

Due to the unaffordable medical system and the fear that he would be blamed back home for being influenced by the Americans — an accusation that in Pakistan can lead to threats against one’s family — he decided to seek asylum in Canada, which is considered more neutral.

He was granted Permanent Residency in early 2021.

Haider is grateful for Canada’s health system and the sense of community support he has found here.

He has even been able to become a licensed psychotherapist, and says he is likely to find a job this year. He aims to support refugees in Canada through counseling and mental health services.

His own experiences, however, continue to haunt him. He says the torture he endured during his abduction continues to affect his physical and mental health.

“I had developed post-traumatic epilepsy,” he says, which was diagnosed much later.

The blasphemy allegations have also affected Haider’s relations with the Pakistani diaspora in Canada. To avoid any untoward incidents, he says he usually has a friend accompany him to religious places — “so I feel safe.”

Recently, he was invited for a talk by fellow community members in Calgary, but another group from the same community “distributed pamphlets against me,” he says, obstructing his participation in the event.

Haider is currently translating a collection of poetry and continues to raise his voice against blasphemy laws and human rights through social media.

Haider says he has resigned himself to his new reality as a permanent resident in Canada, where, overall, he and his wife and son “have no complaints.”

He nevertheless holds on to the hope of reuniting with his family at some point, including his parents, whom he has not seen for years.

“I don’t know if I’ll collect enough money, even to invite them on a visit visa,” he says.

So, for now, he waits and writes.

This article is based on the results of the first Canadian study on the socio-economic conditions of first generation immigrant and refugee journalists, currently underway.

Please complete our survey on immigrant and refugee journalists here .

Tazeen is based in Mississauga and is a reporter with the New Canadian Media. Back in Pakistan where she comes from, she was a senior producer and editorial head in reputable news channels. She holds a master’s degree in Media and Communication and a certificate in TV program production from Radio Netherlands Training Center. She is also the recipient of NCM's Top Story of 2022 award for her story a "A victim of torture, blogger continues fight for human rights in Pakistan"

[…] Source: A victim of torture, blogger continues fight for human rights in Pakistan […]

There is no doubt that Salman Haider was greatly disturbed by the establishment and religious extremists and threatened his life.

This is what happens to people in Pakistan , influential people make lives of people miserable..

Excellent