This year’s Persian New Year—called Nowruz—will look different among the Iranian diaspora in Canada, in the wake of ongoing protests and subsequent crackdowns by Iran’s regime.

March 20th will mark the first Nowruz since the Woman, Life, Freedom movement began in Iran following the death in custody of 22-year-old Mahsa Amini who was arrested for allegedly violating the country’s strict dress code requiring women to wear hijabs.

“For many of us who live in diaspora, celebrating Nowruz, this time, has a different meaning and ties to more complex emotions,” said Niloofar Hooman, a Ph.D. candidate in the Department of Communication Studies and Media Arts at McMaster University, Canada. “We have a heart full of pain and wounds, but we are more hopeful than ever for the tyrant’s fall.”

Amini’s death in the custody of Iran’s morality police put a spotlight on women’s rights in Iran and sparked anti-regime demonstrations in the country and worldwide, including here in Canada. The Iranian regime, led by religious Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei, responded brutally through mass arrests and death sentences.

According to Amnesty International, 22,000 people have been arrested in Iran since the start of the protests, and there is evidence that detainees—including children—have been tortured, raped, and sexually assaulted by state agents in custody. As of Dec. 7, at least 481 people have been killed in Iran since the beginning of the anti-government demonstrations according to the U.S.-based Human Rights Activists News Agency.

With protests against the regime continuing in Iran and around the world, the celebration of Nowruz takes on a new significance this year, as Iranians in Canada say they may use the occasion to commemorate the lives lost and to call for justice and reform.

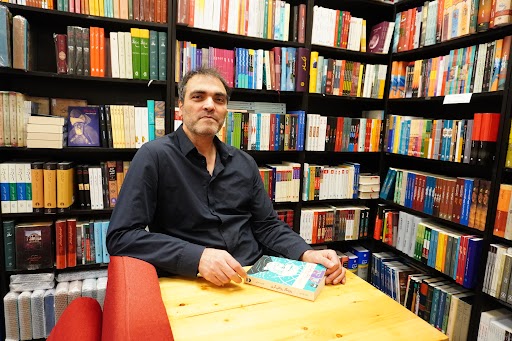

“The spirit of the protests has influenced how the Iranian community is approaching Nowruz this year, creating a paradoxical situation,” said Darius Zamani, an Iranian graphic designer and the owner of PanBeh, an Iranian bookstore that has been operating in Vancouver since 2009. “There may be a greater emphasis on commemorating those who have lost their lives during the demonstrations.”

Watching from afar

According to information from Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada (IRCC), Iranian immigration significantly grew in 2021. The country welcomed over 11,000 Iranian immigrants, ranking Iran as the eighth most prevalent source of new immigrants in 2021.

Iranians who settled in Canada have watched the protests unfold from afar, Hooman said, with a mix of pride and worry.

“For those of us living in Canada, due to the time difference with Iran, during the past few months, we have [woken] up every day to the news of execution, arrests, and direct shootings [of] protesters by the regime’s forces,” Hooman said. “To hide their crimes, the government shut down the internet, so many of us could not contact our families in Iran for several weeks. We spent days and weeks with fear, sadness and anxiety about what was happening in our country. But besides those anxieties, we were amazed and proud of the young people who resisted and stood against the regime’s forces with empty hands.”

A typical Nowruz celebration involves a family gathering on spring equinox, the display of decorative items called ‘Haft-sin’ that symbolize life, growth, and prosperity, spring cleaning of homes, and visiting with friends. The festival dates back thousands of years, originating in the Persian religion of Zoroastrianism, and is celebrated by millions across the Middle East, West and Central Asia, the Black Sea basin, the Caucasus and elsewhere. According to Zamani, it’s essential to keep the celebration intact.

“People do not tend to skip the Nowruz celebration because this is exactly what Iran’s regime is looking for. They don’t want us united,” Zamani said. “On the other hand, the Iranian community in Canada cannot be happy because people in Iran are not happy.”

He and Hooman suspect that this year’s Nowruz will make for more solemn and commemorative gatherings compared to past years.

In general, the differences in the way Nowruz is celebrated by recent Iranian immigrants and those who have been in Canada for a longer period can be influenced by factors like level of assimilation, availability of social networks, and personal preferences.

“In Nowruz, the family is the main focus, and family socializing is essential and a key to the customs related to it. But it is a massive absence for immigrants far from their families,” Hooman said. “Therefore, many newcomers make video calls with their families in the first minutes of the beginning of the new year, using different communication platforms such as Skype, WhatsApp, etc., filling this lack to a certain extent.”

But for those who’ve lived in Canada for a long time, Hooman notes their celebration often involves close friends instead, keeping the spirit of Nowruz alive when they’re far from family.

“The Nowruz behaviours of immigrants according to their circumstances may change over time, but what is common between both groups is that Nowruz is nostalgic for them: they want to keep their relationship with Iran and their cultural identity,” Hooman added.

A Vancouver B.C based journalist who writes about the Iranian community in Canada, art, culture and social media trends.