Immigrants to this country are generally happier than the folks they left behind in their ancestral nations, but most diaspora communities report they are less satisfied with life here than their Canadian-born peers, according to a study just released by Statistics Canada.

The study found that newcomers from Colombia are the only group less happy than the population of their home country, while those from the Netherlands and New Zealand show little improvement. Another set of outliers are immigrant communities from Nigeria, Italy and Mexico, who unlike other immigrant groups are, in fact, happier than the Canadian-born.

Not to be confused with the Bhutan-inspired Gross National Happiness or the Happy Planet Index, this latest study is the first anywhere in the world that tracks happiness – or “life satisfaction” as the researchers prefer to call it – as immigrants move from one set of socio-economic conditions to the Canadian reality. (Happiness could be viewed as more transient and fleeting.) While there are any number of studies of immigration from an economic standpoint, this one looks at the movement of people as a quality-of-life choice: one at least partly motivated by the pursuit of happiness.

“Life satisfaction among recent immigrants in Canada: Comparisons with source-country populations and the Canadian-born” uses data collected by previous surveys in Canada and 43 other countries that have large diaspora communities in Canada (“source countries”).

The surveys asked all Canadian respondents, both newcomers and native-born, the same question: Using a scale of 1 to 10 where 1 means “Very dissatisfied” and 10 means “Very satisfied,” how do you feel about your life as a whole right now? Overseas, the question varied slightly: All things considered, how satisfied are you with your life as a whole these days?

The results, therefore, are based on individual perceptions or “self-reporting,” rather than any kind of objective measure. Those who responded to the surveys were not making comparisons themselves.

The study, conducted by three researchers at Statscan, Kristyn Frank, Feng Hou and Grant Schellenberg, covered immigrants who have been in Canada for less than 10 years. However, the team also analyzed data sets for those who have been in Canada for less than 20 years and found their results remained more or less consistent.

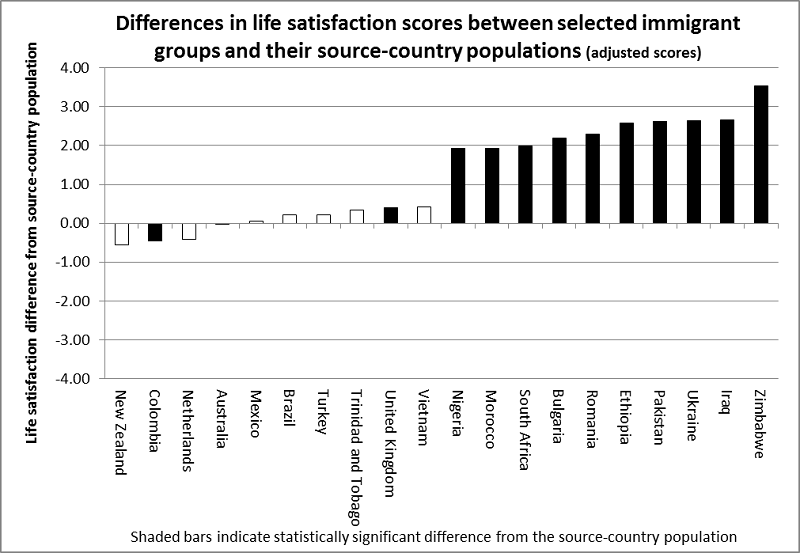

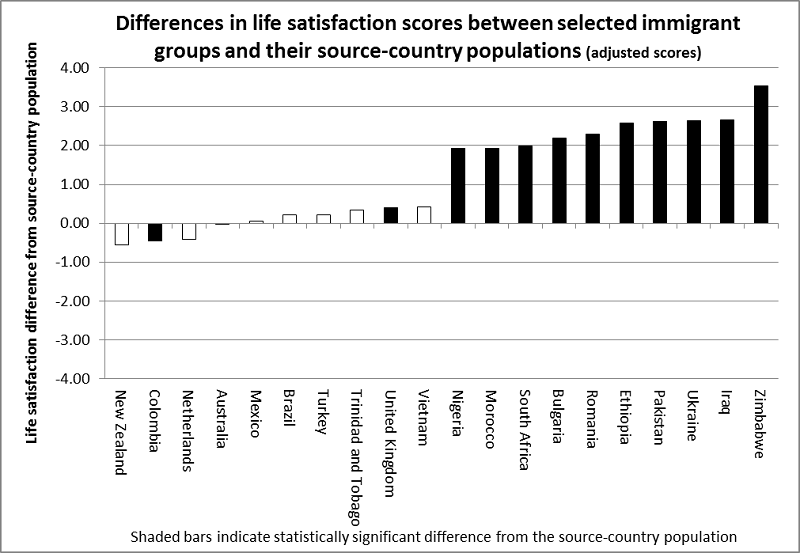

Comparison with source nations

The team of Statscan researchers found that except for newcomers from three nations – Colombia, the Netherlands and New Zealand (all fairly small contributors to Canada’s immigrant population) – had happiness scores that were lower than citizens of the countries they left behind.

Here is a summary:

Immigrants from Colombia had life satisfaction levels that were significantly lower than their source-country population (0.46 points lower). Immigrants from the Netherlands and New Zealand also had lower life satisfaction levels than their source country populations, but these differences were not statistically significant.

Immigrant groups with life satisfaction scores similar to their source-country populations were Australia (no difference), Mexico (difference of 0.05 points), Brazil (difference of 0.22 points), United Kingdom (difference of 0.4 points), and China (difference of 0.45 points). Two other major contributors of immigrants were also in this moderately-happier range: India (1.73) and the Philippines (1.01).

Immigrant satisfaction levels well above home nations: The following immigrant groups had the largest life satisfaction differences when compared to their source-country populations: Pakistan (2.61 points higher), Ukraine (2.64 points higher), Iraq (2.65 points higher), and Zimbabwe (3.53 points higher). All of these results were statistically significant differences.

Accounting for differences

Given that there are vast differences between Canada and some of the nations being compared, the researchers factor in economic development (using GDP data from the World Bank) and the prevalence of civil liberties (tracked by Freedom House) before arriving at the final scores. In e-mailed comments to New Canadian Media, Dr. Frank, a senior research analyst, said raw scores are “adjusted” using a statistical method called regression analysis.

Interestingly, economic differences far outweighed the influence of civil liberties (freedom of expression, assembly, association, education and religion) in determining the final happiness score.

“The regression results indicate that when we control for both source-country GDP and civil liberty, only the effect of source-country GDP is statistically significant. This indicates that immigrants who come to Canada from nations with lower GDP per capita [poorer nations] generally have larger improvements in their life satisfaction compared to their source-country population.

“In a separate model, we also found that about one quarter of the variation in life satisfaction across source countries was accounted for by GDP per capita. These results again indicate that immigrants from countries with lower levels of GDP experience greater improvements in their life satisfaction,” Frank said in exclusive comments. For example, for India, the difference in “life satisfaction” between the resident population and immigrants in Canada went down from 2.04 to 1.73 points when the difference in GDP was taken into account.

Further, the researchers were able to show that the ‘happiness gaps’ remain even though immigrants may not be representative of the general population in the countries they come from, given that they tend to be drawn from the middle and upper classes. The survey data in Canada covered those immigrants who continue to stay in Canada: only the relatively successful persevere in Canada. A separate Statscan study released in 2006 reported the phenomenon of “out migration.” It found that as many as 35 per cent of male immigrants (mainly principal applicants) who have been in Canada for under 20 years return to their home countries, with the bulk of them returning in the first year after arrival. This return to their homelands is most acute in times of economic recession, when the researchers found the exit rate could reach as much as 50 per cent, as in the early 1990s.

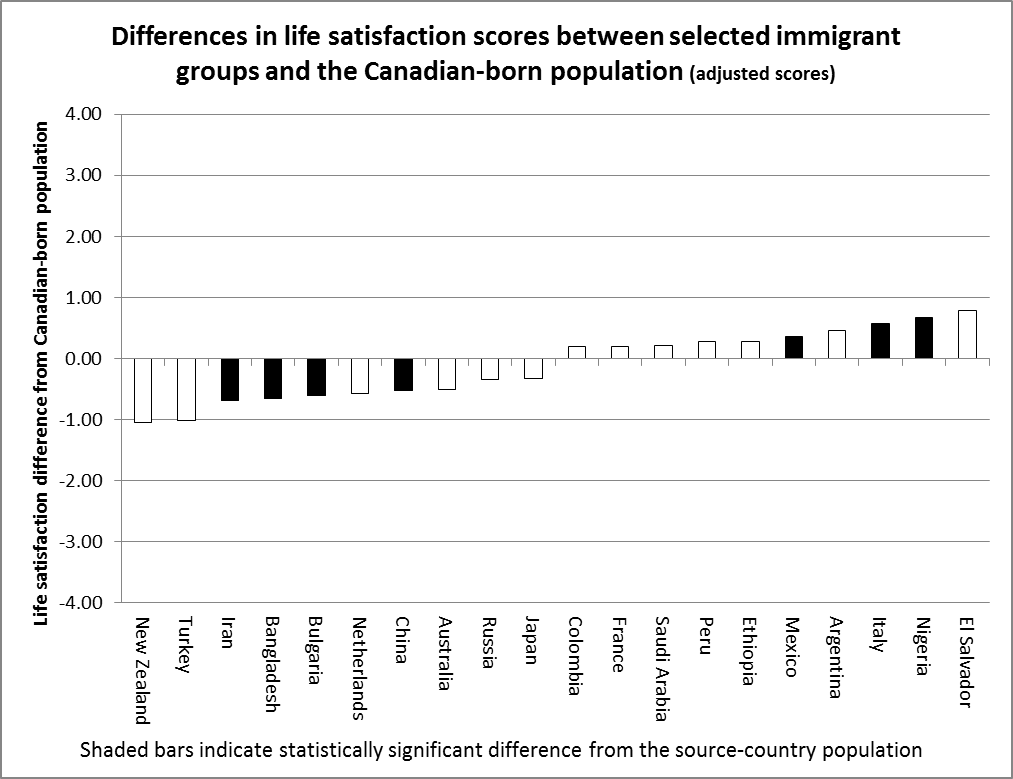

Comparing immigrants and natives

The differences between newcomers and their native-born citizens are less dramatic, but the Statscan study found that 27 immigrant groups reported levels of satisfaction that were lower than their Canadian-born citizens. Here is a summary of the findings:

Immigrant groups with significantly lower life satisfaction levels than the Canadian-born population: Bangladesh (0.66 points lower), China (0.53 points lower), Iran (0.7 points lower) and Bulgaria (0.6 points lower).

Other than China, the other major contributing nations showed differences that were slightly higher: Pakistan (- 0.14) and India (- 0.10).

Immigrant groups with satisfaction levels closest to the Canadian-born population: The groups with the smallest difference were the United Kingdom (no difference), Germany (difference of 0.02 points), United States (difference of 0.05 points), Poland (difference of 0.06 points) and Romania (difference of 0.06 points).

Three immigrant groups had life satisfaction levels that were significantly higher than the Canadian-born population: Nigeria (0.67 points higher), Italy (0.58 points higher) and Mexico (0.36 points higher). Filipino immigrants were happier by 0.17 points.

“Overall, when we compared immigrants as a single group, we found that they had lower levels of satisfaction than the Canadian-born population. However, the difference is small (0.12 points lower than the Canadian-born) compared to life satisfaction differences between various immigrant groups and their source countries.

“When we separated immigrants by country of origin, we found that many groups did not differ significantly from the Canadian-born population. We concluded that the lower life satisfaction observed for immigrants overall may be influenced by certain immigrant groups with particularly low life satisfaction. Therefore, when examining immigrants’ satisfaction in Canada, the variation between different immigrant groups in life satisfaction should be considered,” senior analyst Frank said in her interpretation of the data.

Explaining the differences

Citing previously published research, the Statscan group noted that the lower scores for most immigrant groups when compared to native Canadians may result from factors such as the kind of reception they receive on arrival, separation from extended families, experience of discrimination, regional factors (high rate of unemployment or the proportion of immigrants), or even a “perceived drop in status due to a shift in their reference group.”

The reasons for migration are also a huge factor, the researchers point out. For instance, immigrants from Hong Kong who arrived in Canada for economic reasons reported that they were less happy than those who migrated for social, political or educational reasons.

Summarizing their findings, Frank, Hou and Schellenberg write in their paper, “These patterns are consistent with the view that national contexts influence life satisfaction and that the common experience of life in Canada is associated with a narrowing range of scores across immigrant groups.” Their study shows that the gap narrows for immigrants who have been in Canada for up to 20 years, but that’s as far as they go with the data available.

Happiness further down the road remains moot and perhaps the topic of a longer-term study to determine if the ‘happiness gap’ between immigrant and native-born disappear over time.

Publisher’s note: We have made every effort to present the findings accurately and relied on interpretations provided by Statscan in our reporting. For details on methodology and data collection please consult the original paper available on the Statscan website. The graphs were provided by Statscan.