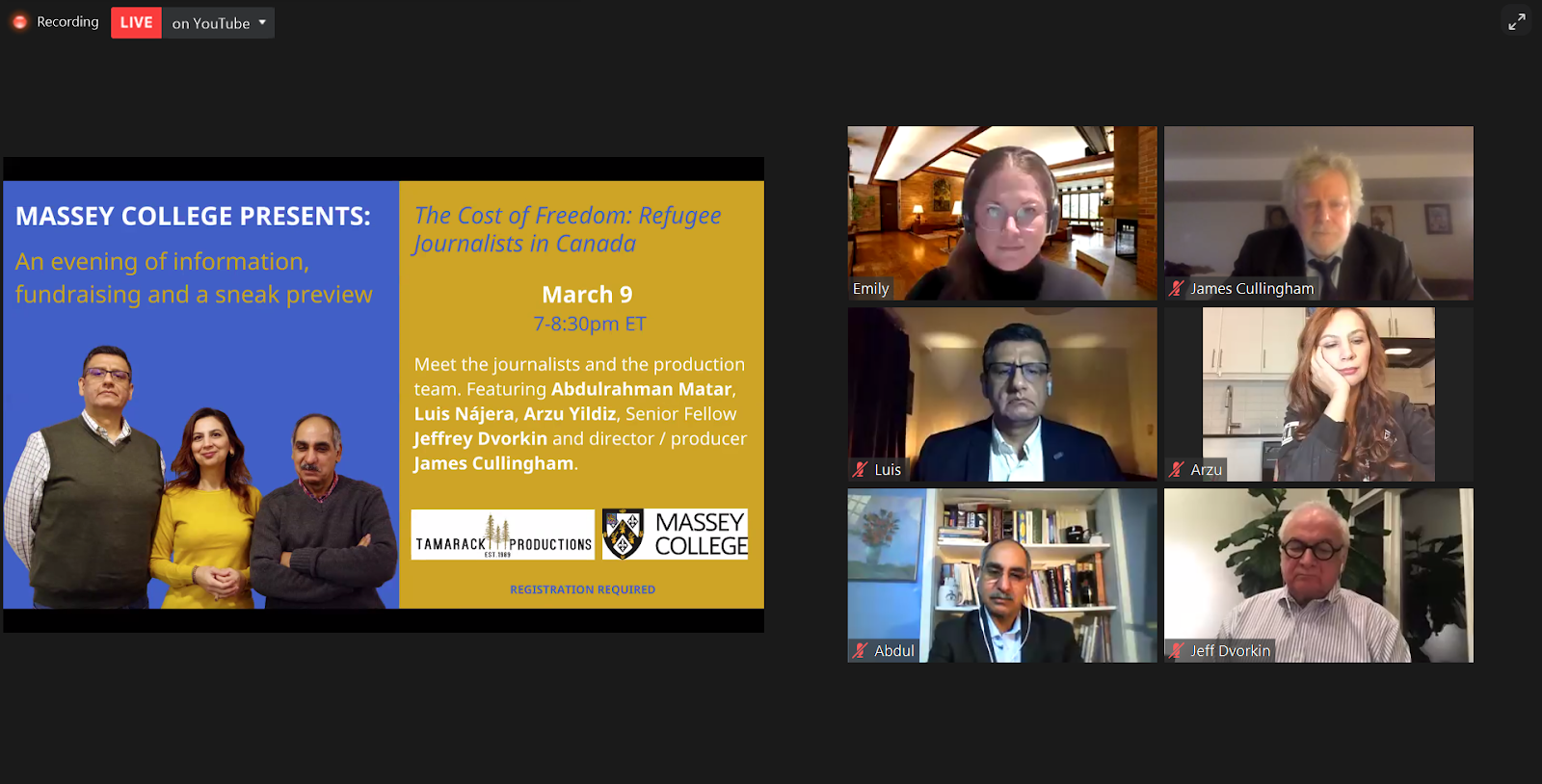

The freedom of press is not equal across the world, a fact too well-known by refugee journalists. James Cullingham, an award-winning documentary filmmaker, spoke with Jeffrey Dworkin, a senior fellow at Massey College, to discuss his upcoming documentary The Cost of Freedom – Refugee Journalists in Canada, scheduled for release later this year.

The documentary profiles three refugee journalists —Abdulrahman Matar, Luis Nájera and Arzu Yildiz — all of whom share the lived experience of the threat to journalists and how Canada came to be their safe haven. Their individual stories of writing in exile highlight the compelling struggle for free speech.

The Cost of Being a Journalist

Fleeing their home countries and seeking asylum has not come without detrimental costs that each has paid. Leaving behind their life, Matar, Nájera and Yildiz shared the extreme hardships of seeking freedom and safety for their life-threatening work of exposing injustice.

Matar is from Raqqa, Syria and once worked in Damascus and Tripoli, Libya as a journalist. After being imprisoned five times for his work, he fled to Canada in 2015 as a refugee and now lives in Richmond Hill, Ontario.

“I’m looking for peace, for protect. I’m left my country after five times in the jail for my opinion, for my writing. The Syrian government…they want to kill me if I continue to writing or stay in the Middle East,” Matar said.

Nájera is from Juárez, México. He and his family fled to Vancouver in 2008, barely saying goodbye to his parents, after receiving a direct death threat. Now Nájera lives in Toronto with his wife and three children. In 2015, the family became Canadian citizens.

“The day that I left my country I have no idea if there will be a future for me and that, unfortunately, continues to be the rule rather than the exception, said Nájera.

Yildiz worked as a court reporter in Turkey and was a respected national broadcast and print journalist. In 2016, she was forced to flee Turkey after months of hiding out when the regime of Recip Tayyip Erdoğan began a witch hunt for journalists.

“Sometimes I had a dream police came to my house. Every time when I wake up, ‘Oh thanks to God I’m here [and] not at home.’”

Left behind were her colleagues, parents and her two children Emine and Fatma, both of whom have now been reunited with their mother.

“I died when I was 35 in Turkey that day which I had to live,” said Yildiz. “And then I born here November 24, 2016. This is my second life when I came here…Many of my friends in a political period in prison right now. I live with the shadow of them in front of me. I cannot continue my life forgetting how the situation.”

Struggles of Refugee Journalism

Although each would be delighted to have a job in the journalism industry, they have faced many difficulties in breaking into Canadian journalism and being published. One of the challenges being language barriers. Still, the three are continuing to ‘reinvent’ themselves and telling stories, including through their dedication to this film.

Matar currently works on the night shift working the line at a Magna auto parts factory. He said he has been seeking publication through multilingual and ethnic media after pitching to many outlets. He continues to write poetry and organizes literary events for the Arabic diaspora in Canada.

“I have a message…[And] I need the Canadian people to hear me.”

Nájera has recently earned a Masters in Disaster & Emergency Management at York University. Seeking a new career path, he has worked as a house painter, janitor and camera salesperson in Canada.

“I have to reinvent myself again and again and again and again,” he said.

Nájera has written op-eds for Toronto Star, the Globe and Mail and the National Post. He was also a member of the team developing the failed Star Touch Tablet App.

“I also applied to or tried to talk to people in Carleton and Ryerson [University] to get a Masters in journalism. Both institutions told me they don’t have a place for me for several reasons.”

Nájera has continued research on the impact of cartels, military and police on Mexico’s freedom of speech and journalism. In 2010, he received the Canadian Journalists for Free Expression Press Freedom Award.

Yildiz said when she worked 15 hours a day, she thought of nothing but working to make a living in Canada. When she would work as a food deliverer, the most prized time of hers was listening to the news on the radio. Now she is writing a memoir of her flight from Turkey and working on fiction about the lives of political journalists.