Are visible minorities in Canada more likely to contract COVID-19? Doctors and community activists say socioeconomic data does show that unequal access to health care can lead to higher coronavirus infection rates among ethnic groups.

Although national statistics don’t currently exist, preliminary data from Ontario Public Health shows that COVID-19 disproportionately affects people of colour. In Ontario, more culturally diverse communities had three times the rate of infection, four times the rate of hospitalization and twice the death rate of communities that were “least diverse” or predominantly Caucasian. In Toronto, Canada’s biggest and most diverse city, 83 per cent of COVID-19 cases involved people who identified with an ethno-racial group.

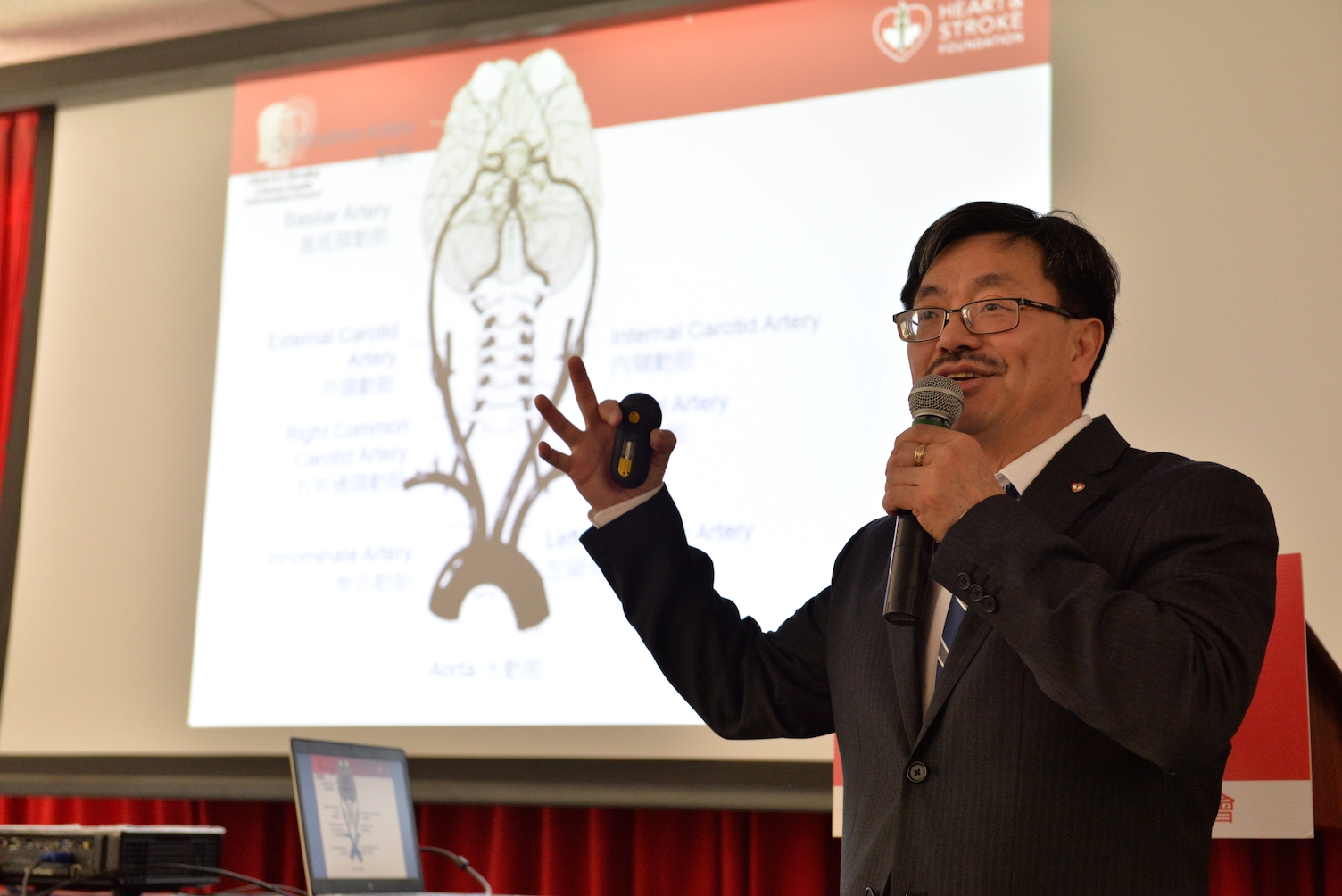

Dr. Joseph Chu, a neurologist and research chair of the Chinese Canadian Heart and Brain Association, is hoping to dig further into those statistics by studying how the coronavirus can damage the heart and brain, and how genetic and lifestyle differences among ethnic groups can affect their health outcomes.

A recent study out of Wuhan, China, found that more than 35 per cent of COVID-19 patients lost their sense of smell, which is an indicator that the virus affects neurological functions. Chu wants to find out more about how the coronavirus can damage the brain stem of patients.

“Just like any viral illness, the coronavirus can cause brain inflammation (encephalitis), brain lining inflammation (meningitis), seizures, confusion (delirium), and strokes” Chu said.

During the COVID-19 outbreak, Chu has been working at Etobicoke General Hospital and treating patients with neurological emergencies.

In the past, he has helped to develop targeted health information for Chinese-Canadians, after studying how factors for stroke risk and recovery are different for Asians. Now he wants to embark on new COVID-19 research to help Black, Indigenous and Asian communities fight the pandemic.

“I have assembled a team of eminent researchers and scientists, including cardiologists, neurologists and clinical epidemiologists, to study the epidemiology of cardiac and neurological complications of COVID-19 affecting visible minorities in Ontario,” said Chu.

Socioeconomic disparities

Health advocate Firdaus Ali says, other than genetic and lifestyle differences, socioeconomic disparities also play a role in determining who is more susceptible to COVID-19.

“Health inequities and disparities have far-reaching impacts for racialized communities, including the diverse South Asian community during the pandemic.”

Ali has worked with Toronto’s South Asian community for more than two decades and says they are among the most vulnerable during this pandemic.

South Asians are the largest visible minority group in Canada and make up 5.6 per cent of the Canadian population. A recent report, The Impact of COVID-19 on South Asians in Canada, reveals that, in Ontario alone, 207,380 South Asians live in poverty. On top of that, 75 per cent of the people surveyed said the economic crisis would impact their personal finances. As a group, South Asians are at greater risk of exposure to COVID-19 because a large proportion of them are employed as essential frontline, low-paying workers in supermarkets and the trucking industry. Thousands are temporary foreign workers toiling in unsafe conditions.

Data from Toronto Public Health shows that South Asians and/or Indo-Carribeans accounted for 20 per cent of all COVID-19 cases in Toronto, despite representing only 13 per cent of the city’s total population.

“They are not ready for change. COVID-19 is a change,” says Ali. She adds that the Canadian government’s universal approach of communicating pandemic information through the mainstream media and its websites doesn’t necessarily get through to South Asians. That means many may not be getting the vital health information they need to stay safe.

“If they don’t get information from their trusted sources, like places of worship, religious leaders and community leaders, they won’t understand the deeper meaning of it and they don’t act on it,” Ali says.

Countering misinformation

Race-based research is also necessary to counter misinformation. In April, the Chinese Canadian National Council for Social Justice conducted a phone survey of 1,130 adults from Canada’s largest cities of Toronto, Vancouver and Montreal. It found that four per cent of respondents believed wrongly that all Chinese or Asian people carried the coronavirus.

The reality is much different. Data from Richmond, B.C., shows that the city has the lowest number of COVID-19 cases in the province, even though half of its residents are of Chinese descent. That shows Chinese living in Canada have a significantly lower COVID-19 infection rate than the general population.

But Dr. Gordon Moe, a cardiologist and researcher at St. Michael’s Hospital in Toronto, says that statistics may not be a true indicator of health. Instead, it could point to missed diagnoses. Moe hypothesizes that cultural barriers may be preventing some Asians from accessing the health-care system during this pandemic.

“When getting sick, they [Asians] probably wait for a little longer before seeing medical personnel, compared to white [patients], for example. I will suspect they have less access to health-care delivery not because of systemic issues, but because of culture issues,” says Moe.

“They are probably more embarrassed to seek medical help.”

He also argues that the data showing low COVID-19 fatality and hospitalization rates among Asians is not necessarily correct because it lacks baseline comparisons of socioeconomic inequalities and risk factors.

The pandemic could last for years, and Moe says he hopes that the proposed race-based research in Canada will help ethnic groups have more awareness of health issues and improve access to the medical system.

“If you don’t know the diagnosis, we’re sitting in the dark,” he said.

Photos by Shan Qiao. Data provided by Marina Giantissos.

This story is a part of the “Immigrants on the Frontlines of Fighting COVID-19” series made in partnership with The Canadian Press.

Shan is a photojournalist and event photographer based in Toronto with more than a decade of experience. From Beijing Olympic Games to The Dalai Lama in Exile, she has covered a wide range of editorial assignments.