To an outsider, the streets of Brampton and many who walk them are a mystery.

Even for some longtime residents there are ghosts who walk among them.

Sometimes the collision of cultures that have gathered here from across the globe is overwhelming. Sometimes it’s just a blur.

But their stories are relentless, travelling here only partly shaped, as the city writes the next, and perhaps final chapters.

To the incurious, these stories will remain hidden. The men with the bright turbans and flowing grey beards who walk the sidewalks in their white silk garments, who are they? What brought them here?

It’s difficult to unlock their lives.

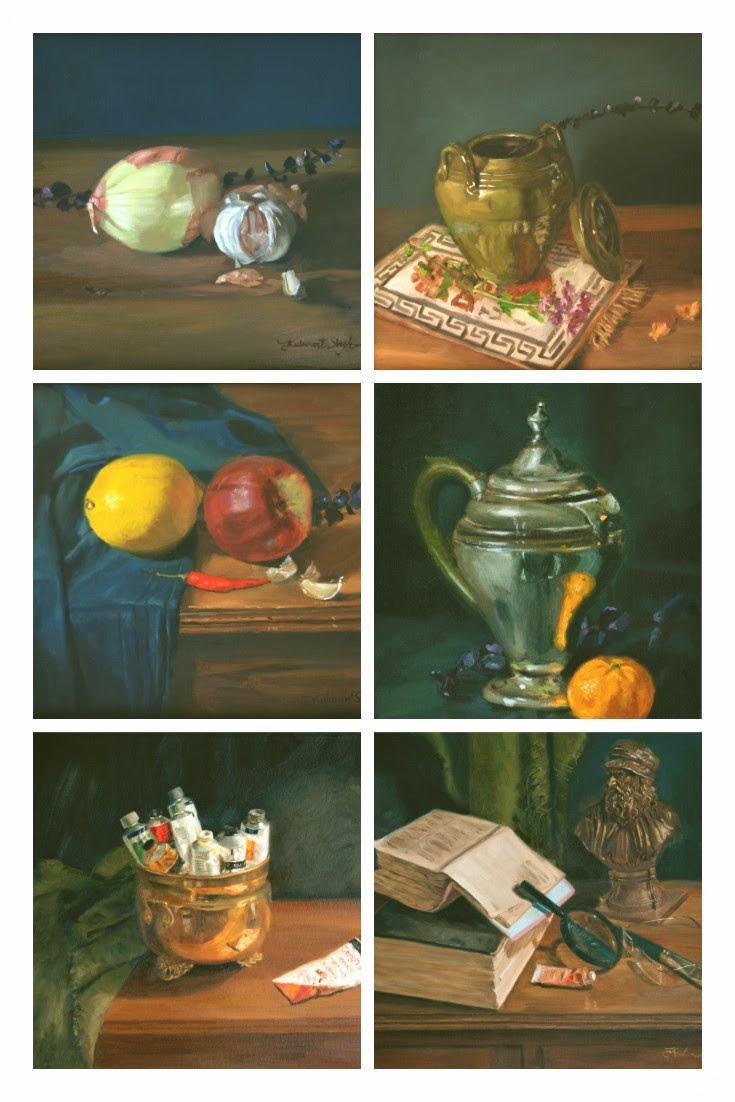

Unless you’re in the company of Kulwant Singh, whose stories are shaped and expressed in vivid detail. They exist in his oil paints. And on the canvases where the colours and shapes and symbols tell the story of his struggle. And his hope.

One of his paintings that he shows is both earthy and unsettling, with a polluted red and brown sky.

A blue cactus twists its way into the frame beneath a turbaned man on a ladder. He is working on a streetlight, his hands folded over the glowing bulb. Singh is the man, created by his own hands that spread and defined the texture and shape and colour of the paint to create the form of himself depicted in his art. He is both subject and artist. Isn’t that the case in all art? It is his own inner self, his essence, his struggle and elation, on display. The man seems oblivious to what his ladder stands over, the artist’s blank canvas, lying on the easel cast aside below him.

There are many paintings like this one in Singh’s portfolio. Though they were created during a time of turmoil and uncertainty in his life, he flips through the large, crinkling sheets with a clear smile on his face.

He once used paint to pour out all of his frustration, pain and worry. Forced into a career that he didn’t want, Singh felt the flame of his passion being snuffed out right before his eyes. Forever an optimist, Singh will tell you it was nevertheless an exciting time in his life, and there were always glimmers of hope. Canada has inspired and almost defeated him. In many ways, it remains his muse.

A portrait of former mayor Linda Jeffrey next to others of Canadian children

In immigrant communities like Brampton, stories of struggle become ingrained in the fabric of the city, they become almost ubiquitous in these places that house our country’s dream of welcoming newcomers whose lives define the modern Canadian narrative.

Like the painting, vivid in colour but dark in subject, Kulwant Singh is a man of dichotomies.

For almost 20 years, Singh has lived in Brampton. After getting married and moving from Punjab in the northwest of India, he has worked as a punch-press operator, truck driver and construction worker. He’s plunged 1,000 metres underground in the potash mines of Saskatchewan. He currently works the assembly line at Brampton’s Fiat/Chrysler auto plant.

He’s a worker, through and through. It’s a quality he inherited from his particularly strict father.

He’s also a painter, a spectacular one.

For two decades in this country, the 50-year-old Singh has struggled to find a market for his paintings, despite critics, teachers and fans in awe of his beautiful portraits.

He has always sketched or painted. It’s in his DNA, like a composer who lives amid the notes in her mind or a physicist who sees nothing but equations and patterns.

Singh’s fight, like so many immigrants trying to fulfill their burning purpose, is more common than you might think.

“There was a filter on my eyes; I was looking at everything through art,” Singh says.

This was in kindergarten. Pencil in hand, Singh was already putting lead to paper and creating art.

As he grew up, his drawings evolved from childlike doodles into rough portraits of the people he looked up to.

“I was very interested, very fascinated by the freedom fighters in India. There was a big struggle for freedom, and those freedom fighters were my heroes,” Singh says.

One such revolutionary was Shaheed Bhagat Singh, a famous, moustachioed fighter during India’s push for independence from British rule in the early 1900s. He was executed at the age of 23.

Portraits of Bhagat Singh online place a crooked fedora on his head, eyes staring back into the camera with a straight-faced look of confidence.

Perhaps it was those early attempts at portraiture, trying to convert that swagger to the page, that imbued Singh with his own sense of confidence. He knew early on that he wanted to be an artist.

“If I’m not good in skills, I spend my time to polish my skills and create some good works. This is my dream,” he says.

He shared as much with his teachers when he reached high school. Many were already well aware of his budding talent. The school held frequent painting competitions, and Singh’s work was usually the top pick of judges.

While he saw his future on a canvas, his father had different ideas and made sure Singh’s teachers understood his priorities.

“My parents are not well educated, (and) my father met my school teacher who was in charge. (My teacher) told them about my wish,” Singh explains. His father didn’t respond well.

“He’s a stupid guy; he don’t know anything,” Singh recalls his father saying. “There is no future in art.”

“Then my father decided to put me in technical school … in electrical,” Singh says.

In May, Singh started working at Brampton’s Fiat/Chrysler plant. The assembly-line gig is the latest in a long string of odd jobs for the artist. He applied for an electrician’s position, but because he didn’t have the proper Canadian certification, he was denied.

But that’s OK by him. Singh says the electricians have a much more rigid schedule, one that would not allow him enough time to paint. As it stands, Singh wrings every minute of his breaks for all they are worth.

“On break time, or when the line stops (is when) I start working,” Singh says with a laugh. He spends his time on the line lost in his own world. He watches the movement of his coworkers, arms lifting auto parts, backs bending, searching for intriguing compositions for his next portrait. When the break hits, he puts those thoughts to paper – paper towel to be exact. Singh has trouble carrying even the smallest of sketchbooks around the assembly plant, so he draws on what he can. When he worked construction it was on pieces of drywall. In the potash mines, as he waited for the elevator to pull the crew back to daylight, it would be napkins or scrap paper.

The many jobs Singh has secured, while not in his preferred field, haven’t been particularly hard to find. The only times Singh found himself unemployed over the last 18 years were by choice, when he tried to focus 100 percent of his energies on painting. Yet he has always been forced to go back to work to provide for his wife and two children.

This drive to find work, whether in a desired field or not, is not unique to Singh. In fact, Statistics Canada data from 2016 shows immigrants who had lived here for at least five years exceeded average national earnings by about 6 percent and were 15-24 percent more likely to be working compared to Canadian-born residents.

The dedication and work ethic of newcomers is one of the big reasons Liberal Leader Justin Trudeau’s government has proposed to increase the cap on economic immigrants allowed into Canada each year. In 2017, 56 percent of the 286,000 permanent residents welcomed to the country were in the economic class. Trudeau proposes to increase the total to 341,000 people in 2020 and 350,000 by 2021, the large majority of which will be accepted under the economic class.

In today’s system, arriving as a self-employed artist is possible with the self-employed persons class, which covers people who could make a “significant contribution to Canada” in cultural activities, athletics and, oddly, farming (though a temporary moratorium has been in place on these applications since February 2018). However, Singh hypothetically could have used his skills as an electrician to apply as well.

The divide between Singh and his father created tension at home. Singh, the baby of the family, was treated a little differently than his five older brothers and sisters.

“My expectations were different from my other siblings,” he says.

In Sikh culture much of the responsibility for carrying on the family traditions and maintaining its social standing is bestowed upon the eldest children. For that reason, without the full weight of expectation on his shoulders, it was tough to put down the paintbrush and pick up the wire cutters of an electrician. Yet he did, and after two years he acquired his trade certificate and was prepared to move on to his apprenticeship.

At the time, his father tried to make amends, suggesting that if Singh disliked electrical work so much, he’d be willing to allow him to swap to another trade. Singh stubbornly refused.

“I said no, I will not waste my years and years in one trade, and then another trade, and then another trade,” he says. “I completed my two-year certificate in electrical and then I joined an apprenticeship.”

Around the same time, Singh encountered a small miracle on a train platform in Punjab.

Waiting for his train home at the end of a long day of work, he overheard something in the cacophony of voices in the station that piqued his interest. Sitting close by, two men were talking about one of their young daughters. Singh moved closer to hear. As the conversation continued, he learned she was doing a bachelor’s degree in fine arts. Singh immediately broke into the conversation.

“They belonged to my city, and I asked him where he lives, and then I met his daughter and asked how to do that,” Singh says.

It seemed too good to be true. With his electrical training behind him and his apprenticeship work ahead of him, Singh began his work toward a BA part-time. However, the glow left behind from the chance encounter on the train platform quickly faded.

“It was a very long struggle for me,” he says. “I was not going to regular classes in school. There was a system where I applied from home to continue classes.”

Part-time classes, but only after a day of electrical work. Most of the time, it felt like the daily work was smothering his true desire. Many of Singh’s paintings from that time bleed with angst. There’s the electrician on the ladder crushing the easel and canvas. In another, Singh is a statue, a bust with no arms or legs, sitting in front of a blank canvas that will never be painted.

In 1993, the hard work paid off. Singh was able to finally secure his BA, and from there everything changed.

“Until that day, I was very uncomfortable … I was feeling I’m not good at anything because I was not getting results. Then when I get that certificate in the art field, then I made [up] my mind,” Singh explains.

He was a grown man now, and regardless of what his father believed, he was going to pursue arts education. He would go on to get his master of fine art degree.

With his head full of new ideas and fresh knowledge, Singh looked outward.

“I was dreaming something big,” he says.

“Something big” arrived in 2001 when he married his wife. He arrived in Brampton a year later.

This narrative, a story of leaving one life behind to start another, is quite common for those who now call the Region of Peel home.

According to the 2016 census, 51.5 percent of Peel’s population is made up of immigrants. A full 35.5 percent of them are from India, like Singh.

For that reason, changes to the immigration system, for better or worse, resonate in this community. With the 2019 election campaign nearing its end, it’s surprising that despite swinging through the region more than 20 times, the three big party leaders have been reluctant to address the question of immigration and the issues that have plagued the system over the last four years.

In November 2016, in the hours before Donald Trump won his presidency, Canada’s online immigration portal was flooded with Americans looking to obtain the proper documentation to flee to Canada. It’s unclear if the crash of the site was partly due to the U.S. election or actually because of an earlier, unrelated problem.

In January of this year, excitement was building as Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada (IRCC) prepared to open online applications for parents and grandparents to come to Canada through the family reunification system. Many were left disappointed. The portal closed after reaching the maximum 20,000 applications. It took just 11 minutes.

”Immigration is the No. 1 topic I hear about in my constituency office. It is what I hear about all the time, because we live in a globalized world where the links are local through technology to places all over the world,” said Liberal MP Sonia Sidhu, speaking in the House of Commons in 2016. Sidhu represents Singh’s riding of Brampton South but has been quiet this campaign on the topic of immigration.

“I do not hear about vague economic ties. It is people’s family members, friends or small business that connect them. Immigration, the movement of people, is at the core of that relationship. The connection our country holds with other countries is enriched and built by individuals. It is about people. Everyone deserves dignity and a fair chance to succeed,” she said.

All of her Liberal colleagues said much of the same at least once over the last four years. Some shared tearful stories of family members breaking down in front of them after failing to reunite with a family member or obtain the proper documentation.

Yet the only success the Liberals wear as a feather in their cap is the shortening of the processing time for citizenship applications from 24 months to 12 months.

“We have been able to address many chronic backlogs in our immigration system,” reads the 2018 annual report to Parliament from the IRCC.

A look at the processing times online suggests otherwise.

On the IRCC portal, if you have yet to file an application, you can expect to wait 20-24 months to sponsor a parent or grandparent or 12 months for a spouse or common-law partner. However, these numbers may not provide a true picture of the wait. As the IRCC states, they are just estimates, based on the number of applications coming in and how fast they expect to process 80 percent of them.

Now, with the Liberal government planning to expand immigration targets, addressing these issues and delays becomes increasingly important. However, all major parties have been dodgy. The Liberals appear content to only reiterate their successes over the last four years and their plan to boost the economic immigration numbers. Conservative Leader Andrew Scheer has not said whether he would reduce these numbers, only that he wants to “set immigration levels consistent with what is in Canada’s best interest.” The NDP platform says it would make family reunification a priority but says nothing about the numbers or ways to improve the system.

When Singh arrived in Canada in 2002, he was part of a surge of immigrants from South Asia headed to the Great White North. This wave of newcomers saw the South Asian-born population in Canada quadruple between 1991 and 2011, with many of them settling in the Greater Toronto Area.

Most often, the decision to leave one country for another is either a push or a pull.

The push factor doesn’t leave people much choice. A war is threatening their family, the economy is collapsing, or there just isn’t any other choice left but to start a new life in a new land.

The pull factors are slightly more complicated. These factors are fuelled by hopes and dreams, perhaps romanticized by family or friends or things seen on TV or in movies.

For Singh, it was a combination of both.

He wanted to make a living with his paintbrush, but the stars just weren’t aligning in India.

For many Sikhs, another factor was the violent years after the mid-80s that defined the struggle for an independent homeland in northwest India. The tension pushed hundreds of thousands out of the country.

With family across the globe — cousins in Germany, a brother in the United States — Singh began to think outside the box. His family and friends also helped with that. He says they would tell him, “Oh, you’re amazing, why are you wasting your time here, you should go somewhere, a Western country, they have a big appreciation for art.”

So, after his marriage in 2001, he decided to take the leap.

“I had already made up my mind when I processed my file to get immigration for here, so it was already in my mind that I wanted to establish there or settle in Canada,” Singh explains. “It was pretty different because nobody was here for me except my wife.” He gave thought to joining his brother in the United States but says the long processing times there convinced him to choose Canada.

The decision to settle in Brampton was simple convenience. His wife, who had previously lived in Canada, had her parents in Brampton. The couple moved in with them for the first four months or so before getting their own apartment.

At the same time, Singh started looking for a Canadian institution where he could obtain some form of Canadian certification in art.

“If I get a certification from Canada in the art field, then I can (get in) somewhere, in school or college, as a lecturer, teaching art,” Singh says. “It was better for me not to do odd jobs, like electrician or driving truck or construction. It was better as a teacher, and at the same time I’m creating my art, but God was having a different plan.”

The desire for his art just wasn’t there.

“I was in a dream. I said no problem, I will do it, I will do it,” Singh recalls. “It was very hard. Now, times have changed, but before that, on every step, I got appreciation from every person, but it was very hard to find the buyers.”

Eventually, he says, his wife got fed up listening to him complain and brought him back down to Earth and the realities of having a new home and two children.

“She said we need money, we need to pay the bills … Responsibilities were bigger, but I was not able to leave my art skills on the side and think I should focus on getting money to pay my bills. I was still thinking I need to paint, I need to create something.”

Yet, he took his first job as a punch-press operator in Brampton shortly after. He later moved on to construction in Burlington, an electrician’s aide, truck driver and so on and so on. During each interlude between jobs, Singh attempted to turn his passion for painting into his career. However, those strong voices from family and friends, the ones who had been so encouraging, pulling him to pursue his art in Canada, had soured.

“They were (now) saying this is not a good field to choose for your life,” Singh says. “My family members, my in-law family members, they were giving me advice, and due to those advisors I started driving truck.”

In 2014, with his truck-driving days behind him, Singh found himself walking down the side of a Saskatchewan roadway at 5 a.m. His boots trudging through the snow, the cloth of his turban protecting his ears from the bitter prairie wind. He heard a car approach, felt something by his head, but he didn’t register what was happening.

“Oh shoot, I missed him,” a voice rang out. The car sped past, and Singh saw a man hanging out the passenger-side window, a thick pipe clutched in two hands.

He was stunned. If the pipe had connected, and he’d collapsed on the shoulder, the large snowbank to his right would have easily concealed his body.

At that time, it had been more than a decade since he’d arrived in Canada. It was the first time he truly felt any kind of discrimination.

Brampton has been good to him, he says. One neighbour takes care of his garden when he gets too busy with work and painting. Another displays Singh’s art in his home like an impromptu gallery and allows him to use extra space for a studio.

Other people aren’t so lucky.

Police said earlier this year that about 107 hate crimes were reported in Peel in 2018, down from 158 the previous year. Intolerance has also been on display during this federal election campaign, with the signs of local candidates being defaced with hateful graffiti.

A poll released earlier this month by Angus Reid found that just over half of Canadians, 52 percent, support Trudeau’s immigration targets. Thirteen percent of respondents said they would increase the targets if possible, while 40 percent believe them to be too high. However, the poll also pointed out how misinformed many Canadians can be when it comes to the immigration system. For example, almost 65 percent of respondents believe Canada accepts most of its immigrants from the Middle East and North Africa. This region only represents about 12 percent of Canadian newcomers.

Singh still holds down his job at the auto assembly, but things have started to improve with his passion. Commissions have started to come in.

His 15-year-old daughter Jasmeen offers a warm smile when asked about her father’s recent successes. She’s watched him struggle for so long. However, she still doesn’t believe he gets enough time to spend on his art.

“On the days he goes to work and comes back, if he feels he has the energy to do some art, he’ll do it. Otherwise he’ll come home and rest, and then it starts all over the next day,” she says. “As my dad has mentioned earlier, an artist really needs to spend time on their work to perfect their skills or to enhance their skills.”

The high schooler would know; she’s looking to follow in her father’s footsteps. Unlike Singh’s own father, he’s embracing this decision wholeheartedly.

“In that way, I’m really lucky. He tells me all the time, ‘Follow your dream, whatever you really want to do, go for it,’” she says.

“It doesn’t matter which field you choose, give 100 percent, 200 percent in that field. Go in deep. Excel in that field,” Singh says. He tells the same to his son, who wishes to pursue engineering.

While Singh has never struggled to find a paying job, he would tell you he’s really struggled to find work. Painting is his real job; the others are just a necessity to support his family.

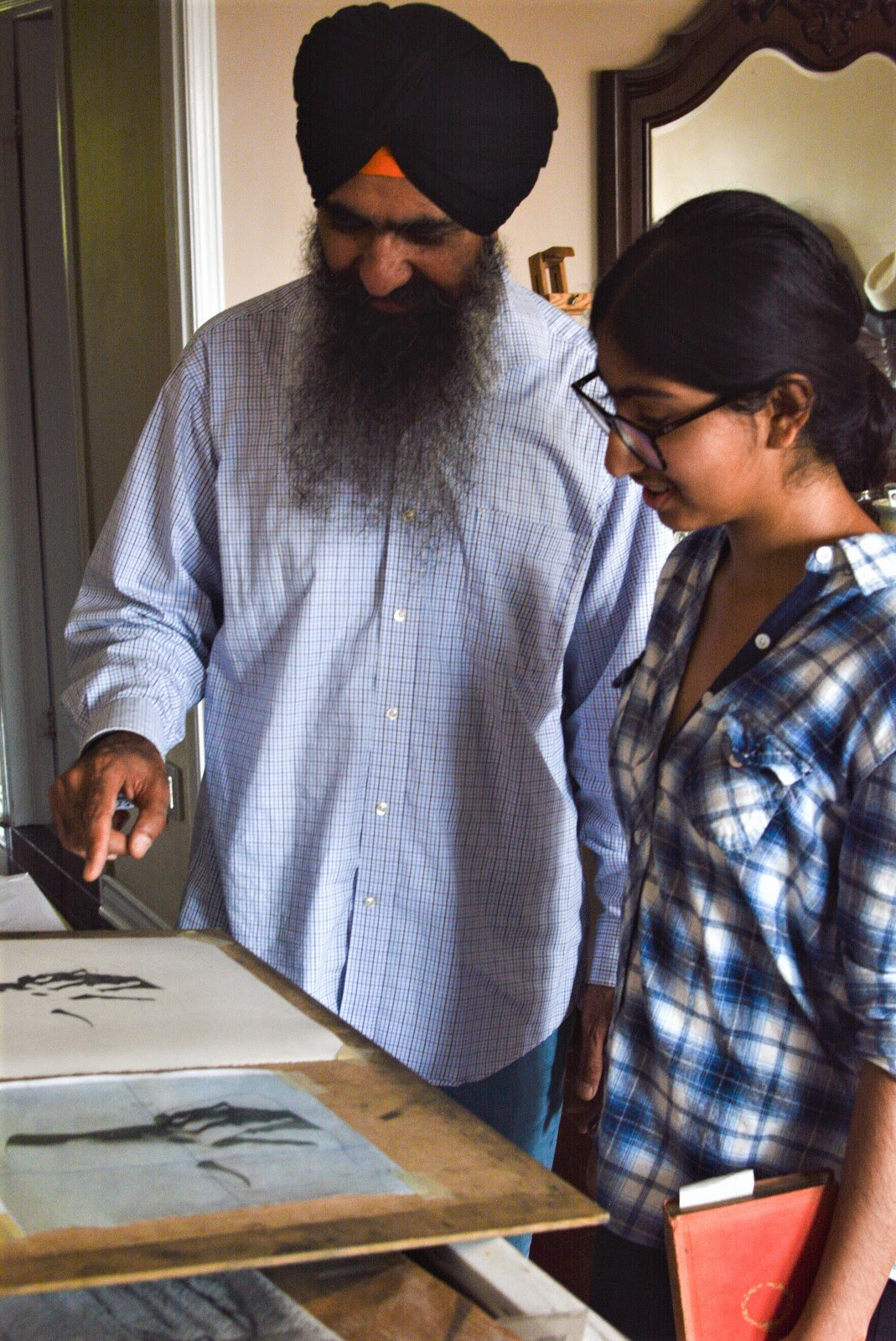

Kulwant Singh with his daughter

The good news for his children, statistically, is that setting up their path to success will be easier. According to IRCC numbers, children of immigrants have a much higher university completion rate (41 percent) when compared to children of Canadian citizens (24 percent).

Regardless, as she’s seen in her father’s story, and the stories of thousands of others who took similar paths to call Brampton home, Jasmeen knows there will be struggle. She welcomes it.

“I feel like the struggle is always part of something you really want to do. If you really want to get somewhere, you’ll have to go through it. There’s no easy path to go.”

Email: [email protected]

Twitter: @JoeljWittnebel