“No one puts their children in a boat unless the water is safer than the land.”— Somali-British poet Warsan Shire, Home

Kim Tran slipped out of Saigon under cover of night. She was 15 in 1981. Her entire life, every second of it, had been spent inside the chaotic world of that city. When she was nine it was renamed after the communist Viet Cong leader, Ho Chi Minh. The fall, or liberation, of Saigon in 1975 – how you viewed it signalled which side you were on – set the world on a different course. Those born in the south, like Tran, clung to the dream of freedom. When the last Americans escaped the country the Viet Cong extinguished those dreams. Democracy had died with all the fallen U.S. soldiers. But not for Tran and thousands like her.

Her mother had owned a large grocery store in the local marketplace. When the government took all their financial assets and the family business, Tran says, “Mom had a nervous breakdown” which she never fully recovered from. “My mom had to raise many of us, a dozen of us, so she always tried to save for us … You cannot have your own business. Everything has to be government owned,” Tran explains.

Her father, a police officer before the government fell, tried to make ends meet with odd jobs – but the kids were forced to work as well. Tran and her sister would sell homemade food on the street after school.

The situation for the South Vietnamese grew more dire every day.

She lived in poverty with her family under communist rule.

After six years, with the help of relatives and friends, she and two siblings blended into the darkness and crossed the city’s fortified border. She had been disguised as a rural peasant. They hid in farm houses as the Viet Cong, known by then as “the Front”, patrolled the countryside. They made it to the water and were put on a wooden riverboat. They began to float toward their destiny on their path to a new world.

On the way to the coastal city of Ba Ria, they hid from authorities who arrested others trying to escape. Tran slipped past. Her brother, in a futile bid for his freedom, had not been so lucky.

Two years earlier, Kyanh Do stepped on to a boat clutching a bag of clothes and some rice. The 17-year-old had memorized a Chinese name – Cao Hot Thanh. Like money, for others, or the right connections, it became the key to his freedom. That simple three-part name will forever be seared in his memory.

The ethnic Chinese, who had controlled much of the private sector, were not trusted by the communist government as it struggled for an economic footing. At the time, they were the only people allowed to leave peacefully.

His mother arranged for him to flee, alone, after the encouragement of his imprisoned father, an engineer previously employed by the toppled government.

“He said communism doesn’t work,” Do recounts, sitting inside his sprawling Mississauga estate. “He said if I died in the sea, he would be OK with that. He said it would be better for me that way.”

Life for Do and Tran had been transformed overnight after the rocket attacks by the North Vietnamese eventually led to Saigon’s capture. The communists immediately upended the existing way of life, completely reorganizing every corner of South Vietnamese society. People were relocated, wealth and property were seized and redistributed.

Students from the North flooded in to get an education in southern schools, as others were denied the opportunities they had grown up with.

“We were treated very differently by the kids from the North,” Do remembers. “They got preferred treatment in many ways.”

“Even to enter high school or to enter university, there is what they call a qualification [program]. If you (or your family) worked under the old government… [you] fail. You cannot get in,” Tran says.

A portion of Do’s home was confiscated; his family was moved upstairs to make room for another family.

While his father languished in captivity, life for many South Vietnamese became similarly imprisoning. Food, though still abundant, was increasingly scarce for them. Menial employment was all that was available.

This was not the life Do had ever imagined he would live. His future had always held such promise. He knew what he had to do and his parents helped push him to run to the sea.

Do didn’t have the stomach for the violent waters on his four-day journey before making landfall, covered in his own vomit. He slept sitting up. “You’re leaning against one another,” Do says, describing the desperate conditions on the boat. He points right next to his body and says: “You put your luggage here.”

Tran interrupts: “You had luggage?”

Tran and Do’s place of birth, is no longer their home. It fell to communism an eternity ago. Opportunity and prosperity had been replaced by starvation and despair.

They were part of the epic migration, some 2 million Vietnamese who fled between 1975 and 1992, dubbed by international media as “the boat people.” They survived the ocean, the Vietnamese navy and Thai pirates, knowing that going back would also likely lead to death. The United Nations estimates that between 200,000 and 400,000 boat people died at sea searching for freedom.

But they made it, after about a week on the water. Wave upon wave of boat people spilt onto the shores of Asian countries. Do arrived in Malaysia, while Tran’s safe shore was in Indonesia. Those were their gateways to the west.

The two met, and married, in Canada. Both say their common experience changed them forever. Much of that transformation began just as their new lives started to unfold.

“I became a man,” Do said.

“I think when I came to Canada, I grew much more,” Tran says.

Today, the couple lives a fairytale life. Do, 57, is an accountant. Tran, 53, is an actuary. They share a palatial home with their four daughters, Natalie, 26, Victoria, 22, Valerie, 17 and Caitlin, 12, in the south end of Mississauga.

“We definitely have a good life,” Do begins. “So that’s why we like to, as I said” … his voice trails as his wife completes his sentence: “Give back.”

The couple now supports the resettlement of people escaping hardship in other lands. They have sponsored four Syrian families and have one more to go. Their reason is simple: at one point they were in the same boat.

Exactly a decade before their continental shift, Canada was just embarking on its own transformation.

In October, 1971, Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau, rose in the House of Commons and delivered a speech that would forever change the look and feel of the country.

Up until the end of the Second World War, modern Canadian society featured two predominant groups, those of French origin and those who traced their roots to Britain.

Trudeau had already travelled the world, backpacking around the globe in his late ‘20s, ostensibly to gather research for his doctoral thesis at Harvard. Earlier trips to Europe and Mexico had sparked his curiosity about life and culture and politics outside the franco-anglo world he had grown up in.

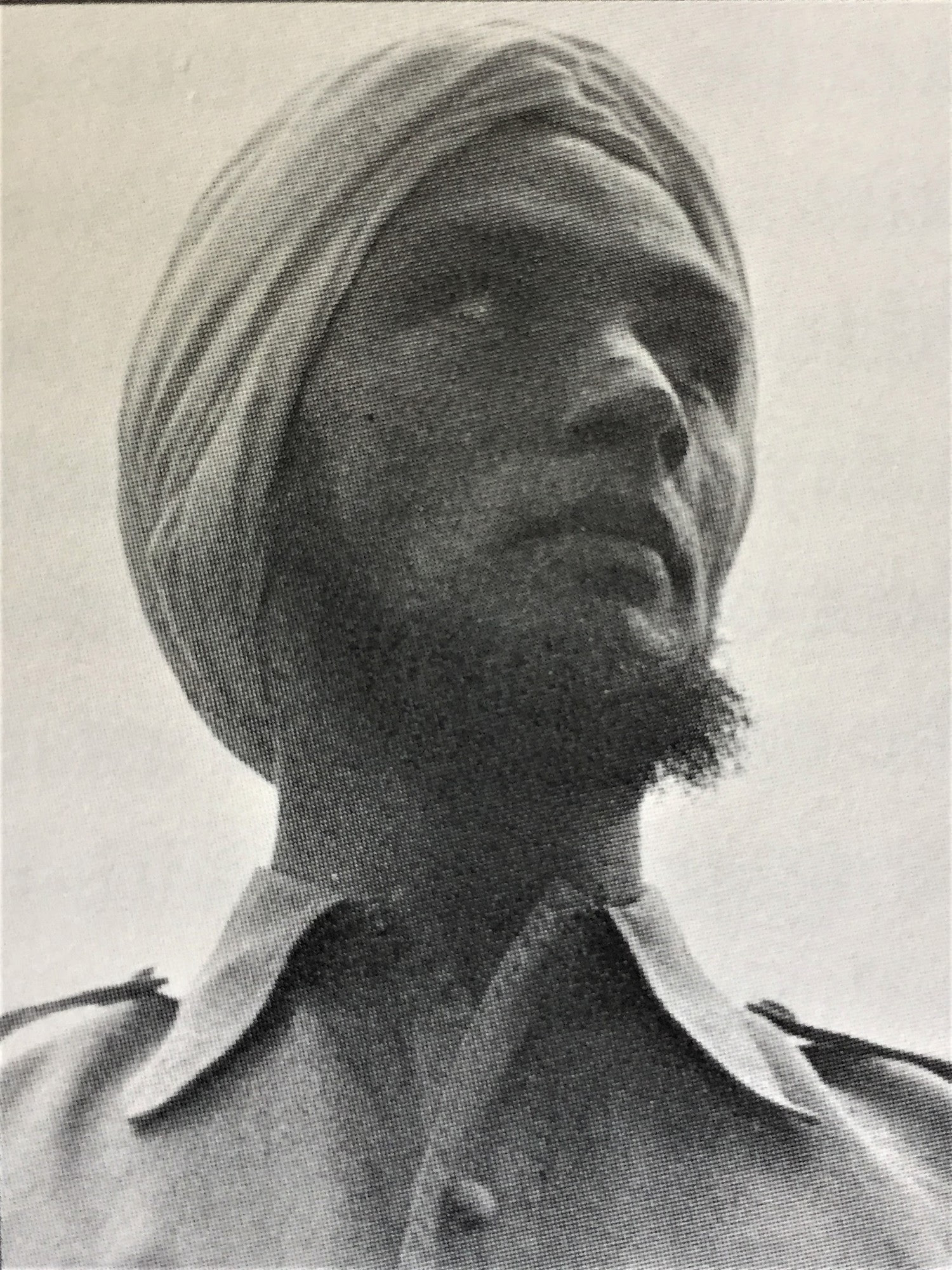

The future prime minister explored through parts of Europe falling deeper into communist rule, China as it just began its emergence following the war and India, where he wore a turban and mixed easily with locals as its newfound independence collided with a range of competing political and ideological interests.

After his return and entry into political life, eventually taking over the leadership of the Liberal party, becoming prime minister at the same time, Canadians were caught up in French-English relations. A Royal Commission on bilingualism and biculturalism, established in 1963, was examining how to preserve a delicate respect between the two solitudes.

Meanwhile, Canada’s attitude toward immigration, especially from outside western Europe, remained typically closed.

The landing tax or a head tax, was a practice the government began to deter Chinese and other immigrants starting in the late 1800s.

“To admit Orientals in large numbers would mean the end, the extinction of the white people. And we always have in mind the necessity of keeping this a white man’s country.” Those were the infamous words of B.C. premier Sir Richard McBride, in 1914, as a ship carrying mostly Sikh migrants from India was turned back from the province’s shore.

Between 1941 and 1949, all Canadians with any Japanese heritage were placed into internment camps, until four years after the war had ended.

Jewish and Italian newcomers who arrived in increasingly large numbers after the war endured constant alienation and outright intolerance, while very little non-white settlement was allowed.

Issues of resentment toward Italian immigrants, in particular, created the first scrutiny of family reunification policies, as upward of 90 percent of newcomers from the southern European nation, devastated by the war, who arrived in Canada between 1947 and 1970 were sponsored by a family member.

But the world, whether upper and lower Canada liked it or not, was changing, after three centuries of colonial rule and the subsequent upheaval.

People wanted a better life. They just needed a place to find it.

It came as somewhat of a shock to many Canadians when the dazzling franco-Canadian prime minister, with his broadly varied experiences and outlook on what a modern society should look like, stood up inside the Parliament on that October day in 1971.

He laid out the reasons why the Royal Commission had been asked to widen its scope, beyond English and French considerations.

“Honourable members will recall that the subject of this volume is ‘the contribution by other ethnic groups to the cultural enrichment of Canada and the measures that should be taken to safeguard that contribution.’ … No citizen or groups of citizens is other than Canadian, and all should be treated fairly.”

It was the launch of Trudeau’s multicultural policy, and without the major shifts – first legislatively and then attitudinally – in the nation’s approach to immigration, Canada would look nothing like it does today.

Starting in the late ‘70s, Canada would experiment with a program that was the first of its kind anywhere in the world.

It was a form of public-private sponsorship of refugees, and for about five years, till the early ‘80s, approximately half those who fled Vietnam, Cambodia and Laos and arrived in Canada, came under this incredible, unprecedented national response to a global humanitarian crisis.

The United Nations, in 1986, bestowed the Nansen Award upon the entire nation and all its citizens for the humanity exhibited by Canadians. It is the only time in seven decades that the honour was given to an entire country.

In 1988, one of Trudeau’s lasting legacies was enacted, with the passage of the country’s official Multiculturalism Act, guaranteeing the legal and moral rights of all peoples to live free from discrimination.

After arriving in Malaysia and Indonesia, both Do and Tran were transferred to refugee camps. At that time they still didn’t know where they would eventually settle. Do says he never thought about where he wanted to go, he just wanted to get out.

They were met by Canadian officials from the United Nations who interviewed them. The Government of Canada sponsored them, under the recently created national refugee program, and arranged for them to come. Do says he only knew about Canada because an uncle had studied here.

He landed in 1979, the same year he left Vietnam, in Granby, Quebec. He stayed there for six months and received training in French and English. He couldn’t find a job, so he decided to look in Toronto. His first job in the city was at a metal-plating factory.

He worked for two and a half years at factories and a Roots warehouse before deciding to go back to high school. It was at Parkdale Collegiate Institute in 1982 where the pair met.

They were struck by their shared history. Eventually, they realized Do’s mother, who was a teacher in Saigon, had taught Tran’s brothers. Life might have been challenging by many people’s standards and the chances of really making it seemingly slim – Do worked as a busboy at a hotel restaurant while completing high school – but after what they had survived, hearing about their remarkable success seems almost like an inevitability.

Eleven years after meeting, the two married. They eventually settled in Mississauga to take advantage of the cheaper housing market and the room to grow. “We found Toronto too cramped and too busy. We didn’t know Mississauga before. But once we got out of Toronto, I think we like living here,” Tran says.

Their four daughters were all born in Canada. They know little of the old country but are familiar with their parents’ story. “I honestly couldn’t even imagine,” Natalie Do says. “Me and [Victoria] have talked [about] if that were to happen now, what would we do? We can’t even think about where to start.” Do himself does not want to go back to Vietnam, and he hasn’t been since coming to Canada. Tran said she went back once for a business trip.

As both sponsors and sponsored people, Do and Tran have a strong interest in Canada’s policies on immigration. While Tran doesn’t want to reveal what party she plans to vote for, Do says he’s ready to vote Liberal.

The Liberal government has set the immigration quota at 350,000 newcomers by 2021. The economic class, made up of businesspeople and highly skilled workers, will make up the lion’s share at 202,000. The family and refugee class make up the rest, with the party planning to welcome 91,000 family members such as children, spouses and grandparents and 51,700 refugees by 2021.

Do says he is generally happy with the Liberals’ numbers but they could be better. He wants the government to take in even more people and both humanize and speed up the immigration process.

Tran agrees, “as long as they [the government] have a plan to make sure they can handle [the newcomers] once they’re here.” Tran believes that the examples of refugees she and her family see are all “good examples” of refugees and doesn’t see them as a burden. “Because I think they will contribute.”

Last January, the federal government debuted a web portal that was meant to make it easier and quicker to bring parents and grandparents to Canada. The government failed to anticipate the demand, and the program was full 11 minutes after the site opened. For Do, the portal represents just one more intimidating aspect of the immigration process. “It doesn’t matter how minimal it is, but please still have some [more facetime with a worker],” Do says.

He feels lucky to have passed through the immigration process so quickly. Both he and his wife, who were sponsored by the government, had social workers help them with their refugee applications the entire way through. Both received their citizenship within three years of arriving in Canada. By 1985, Do’s entire immediate family was in Canada. Working together with his father, who escaped Vietnam a month after he was released from a re-education camp, they worked to bring the family over through private sponsorship. Tran’s immediate family was in Canada by 1990; however, the process was a bit more difficult. “We applied in 1982. It took a bit longer to get them here,” Tran says. She believes the application stalled, though she is not sure why.

Having lived as refugees themselves, the pair answered the call in 2015 when the federal government asked for private sponsors to bring Syrian refugees to Canada. Do recounts the reaction of one family clearly moved by the generosity they were shown.

“We were government sponsored, and these people, we sponsored them. So we have more connection with them,” Do tells The Pointer.

“They came in. We got everything set up for them. His wife, we took her around the apartment … and the bed, it was a very nice bed. They thought they got lucky … She cried, she got so emotional.”

When they told the Syrian family that they are friends now, the father said: “No, we’re family.”

Mansoor Tanweer is New Canadian Media’s Local Journalism Initiative reporter on immigration policy. An immigrant himself, he has covered municipal affairs and the Brampton City Council in addition to issues relating to newcomers over several years.