Sukhmeet Sachal has a grim saying. That COVID-19 is like a storm wreaking havoc, with various communities sheltering in boats – some fully equipped with resources, some with nothing at all.

“[The South Asian community] would maybe be in a rowboat,” he says.

Sachal is a second-year medical student at the University of British Columbia. Nine months ago, he launched an outreach project at Sikh gurdwaras in Surrey, B.C. Now his team of more than 150 volunteers translates and circulates culturally sensitive information about COVID-19 to a community starved for accurate and adequate resources.

Language barriers have been an obstacle in accessing information and not enough information has been translated into South Asian languages, said Sabina Vohra-Miller, an internal medicine specialist.

According to the 2001 Canadian Census, the South Asian community reported more than 75 different first languages.

Messaging apps that misinform

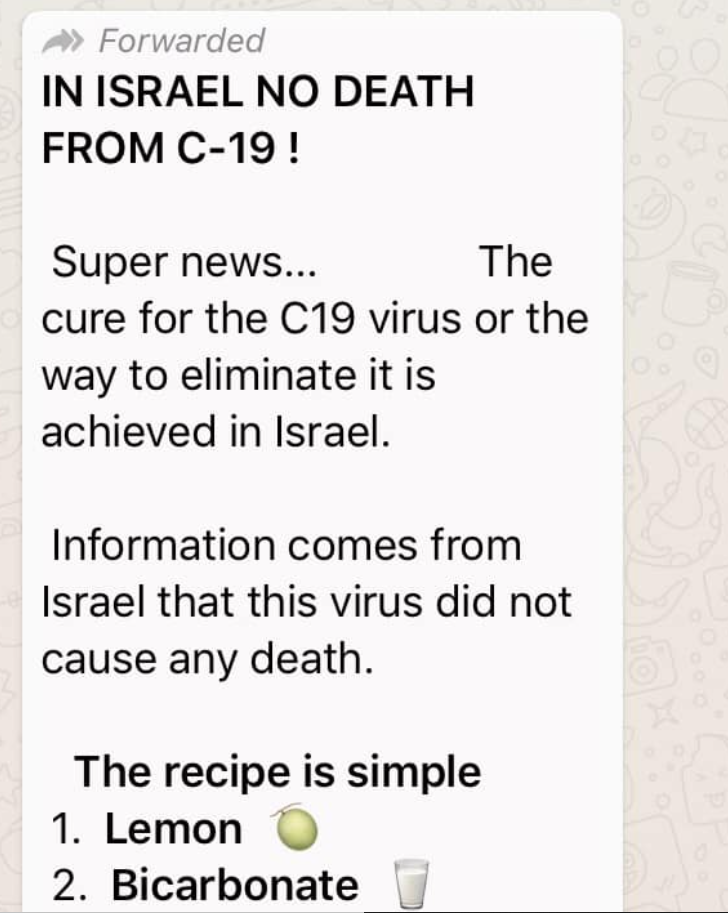

With the pandemic, an older generation of South Asians, who rely heavily on messaging platforms such as WhatsApp or WeChat, is now spending more time on these platforms forwarding messages about COVID-19. This is where misinformation has often played into the community.

“Our parents are not getting that information [about COVID-19] necessarily from the Government of Canada or from public health, Ontario, they’re getting that information from WhatsApp groups,” said Vohra-Miller.

Seema Marwaha is a general internal medicine physician and an Assistant Professor in the Department of Medicine at the University of Toronto. She said as a frontline worker talking to South Asian families and individuals, she soon realized that there was a lot of misinformation and mistrust in the community.

When the resources are only provided in English or French, those resources are very limited in who they reach, she said.

“[There are] two camps, there’s people who just can’t get access to basic questions. And then there’s people that have heard things that are wrong, and you need to dispel those myths for them.”

When they can’t access information and instead are bombarded with misinformation, “it is really, really difficult to sort out what is true and what’s not.”

Marwaha said messaging platforms, such as Whatsapp, are a way for information to be spread unmonitored, easily and quickly, because often these messages are being shared by trusted family or friends.

“Some [misinformation is] based in cultural, or religious grounds. For example, Hindus were very curious to know if there was any gelatin or cow products included in the vaccine development. It’s such a fear for people who are devout Hindu that it planted the seed [of misinformation] and it’s hard to break that,” she said.

This largely impacts the accessibility of the vaccine to members of the South Asian community as they attempt to navigate vaccination bookings and information.

“If you’re Muslim, they wanted to make sure that the vaccine [is] halal and that there was a fatwa”—a ruling under Islamic law—declaring the vaccine halal.

Spokespeople for Pfizer, Moderna and AstraZeneca have said that animal products, including pork, are not part of their COVID-19 vaccines.

Pakistan has a history of being vulnerable to such conspiracy narratives. It has experienced failures of Poliomyelitis (Polio) vaccination programs and remains one of the few countries still fighting Polio.

Marwaha said that misinformation is often bi-directional meaning it’s both homegrown from home countries and sometimes it’s formed ‘right next door.’

High infection rates

The widespread misinformation has led many to believe in conspiracy theories, mythical cures and anti-vaccine movements.

And it may be having a detrimental impact in the most diverse city in Canada. Despite only accounting for 13 per cent of Toronto’s population, the city’s public health statistics show South Asians account for 26 per cent of all Covid-19 cases.

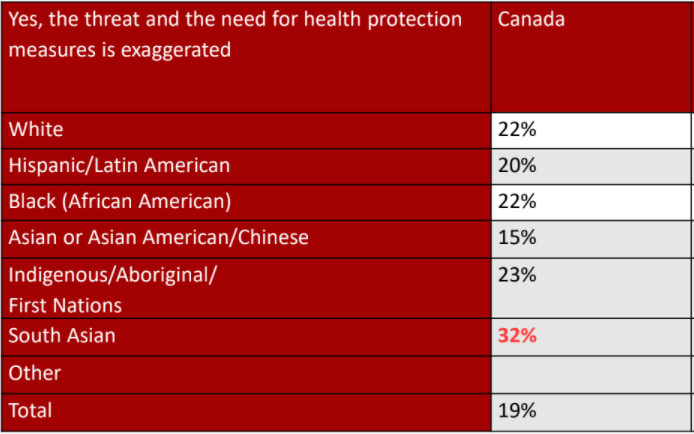

A recent study by The COVID-19 Social Impacts Network, a multidisciplinary group of Canada’s leading experts, suggests that 32 per cent of South Asians believe that the threat and need for health protection measures are exaggerated.

The survey of about 3000 people in Canada is part of weekly or bi-weekly surveys conducted by the Association for Canadian Studies with Léger since March 2020 to monitor the attitudes, perceptions and behaviours of Canadians during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Vohra-Miller added that the National Advisory Committee on Immunizations’ guidelines on who is at greater risk included areas of high transmission, essential workers, race, elderly living in long term care, but oftentimes in the South Asian community, there are intersections of all of these which place them at a higher risk.

In spite of the challenges, Sachal and his army of volunteers continue their work. And it’s making a difference. Not long after the program began, Sachal’s mother heard from a community member who sobbed as he told her he had tested positive for COVID-19. But thanks to Sachal’s efforts, he said, he knew how to self-isolate to protect others. And in the end, he didn’t infect any other members of his family.

________________________________________________________________

This story has been produced under NCM’s Advanced Mentoring program led by Professor Susan Harada and Judy Trinh.