The recent Maclean’s magazine feature labeling Winnipeg Canada’s most racist city lets other cities ‘off the hook,’ says Peter Kulchyski, head of the department of Native studies at the University of Manitoba. He says the conversation needs to expand to cities like Montreal, Vancouver and Toronto.

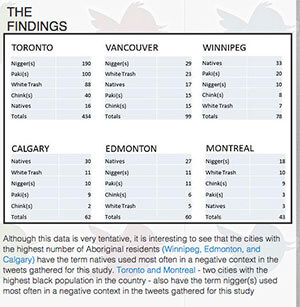

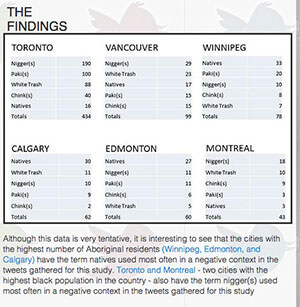

The study that formed the basis of the Maclean’s article tabulated the number of racist slurs used on Twitter in Canada’s major cities, and while slur usage in Winnipeg was highest, other diverse cities such as Toronto and Montreal also saw a high number of slurs used per capita. But while slurs are one of the many ways people in Canada experience racism today, the issue is far more complex than that.

“People are victims of racism when they experience slurs thrown at them, they are victims of systemic racism when they don’t receive adequate service because of the colour of their skin,” says Michael Champagne, a youth leader in Winnipeg’s north end.

“People are victims of racism when they experience slurs thrown at them, they are victims of systemic racism when they don’t receive adequate service because of the colour of their skin,” says Michael Champagne, a youth leader in Winnipeg’s north end.

These issues of racism have predominantly historical roots, says Kulchyski. Like other parts of Canada, Winnipeg has a long history of colonialism, as well as one of racial mixing. When English and French settlers moved into the area, Aboriginal groups were driven out to the surrounding areas. High immigration to the city starting in the 1970s also resulted in the development of several ethnic communities, most of which have grown steadily since then.

But like both Champagne and Kulchyski agree, this is not just a Winnipeg problem. Despite the country’s increasingly diverse demographic makeup, a 2014 survey across racial groups found that 62 per cent of Canadians were worried about a “rise in racism.” So, the question is, how can Winnipeg, and Canada, combat such a deeply rooted-issue?

The Government’s Plan

Several initiatives from the Canadian government have attempted to address these issues across the country. In 2005, the government released the Racism Action Plan, a 62-page report on strategies to improve discrimination across all governmental departments, from Citizenship and Immigration Canada to National Defence.

“[T]he honouring of treaty rights have been very poor.” – Peter Kulchyski, University of Manitoba

It is important to note that Canada defines Aboriginal groups as a separate category from “visible minorities”, creating what is described as “three silos” of minority groups in Canada, which also includes French language minorities. But while Aboriginal issues are treated separately due to historical treaties agreements, Kulchyski says that, “the honouring of treaty rights have been very poor.”

Long-term Solutions

The website started by Winnipeg’s Mayor Bowman is only a start, but larger-scale solutions are also needed, says Champagne. “Winnipeg as a city is going to have to innovate a solution of [its] own, to address this challenge of our own.”

Jenna Wirch, a youth programming coordinator for Aboriginal Youth Opportunities in the north end, believes that large-scale changes need to be made to combat the systemic racism that exists in the city. “There’s already a lot of programs and resources, some overlap each other – but it’s more of a bigger issue than programs.”

“We should not only be acknowledged, but represented at the table, at every level of government.” – Jenna Wirch, Aboriginal Youth Opportunities

For her, going back to her culture and learning traditions, and developing what she describes as a “strong sense of community” in the north end was the most important in escaping the cycle of poverty and violence.

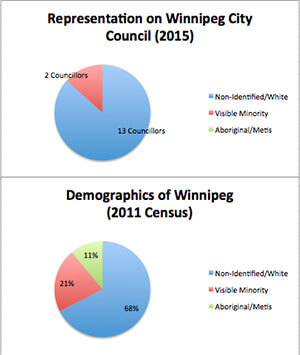

However, participation in government is also important in the fight against systemic racism. “We should not only be acknowledged, but represented at the table, at every level of government,” Wirch adds.

Aboriginal and ethnic minorities have very little representation at Winnipeg’s municipal level, with only two out of 15 city councilors identifying as a visible minority, and zero Aboriginal councilors.

Aboriginal and ethnic minorities have very little representation at Winnipeg’s municipal level, with only two out of 15 city councilors identifying as a visible minority, and zero Aboriginal councilors.

This trend is also reflected across other major, diverse Canadian cities. According to the 2011 report The Diversity Gap, Toronto only had five visible minority municipal council members out of a total of 45. In a similar 2011 study, Vancouver had 10 out of a possible 46 visible minority members on the council. Montreal fared far worse with only three out of 64 city councilors that were visible minorities. Even more concerning is that these statistics largely do not include Aboriginal people as “visible minorities”, making those numbers more difficult to discern.

There is clearly room for improvement in the representation of minorities and Aboriginals at the city level, not just in Winnipeg, but across the country.

Community-level Initiatives

The declaration of Winnipeg as Canada’s “most racist city” has spurred discussions around grassroots solutions that can serve as a starting point for all Canadians.

“Prior to coming to Canada, my only window into the First Nations were from western movies,” shares Shahina Siddiqui, chair of the Islamic Social Services Association (ISSA). “For most newcomers, this is all they know.”

Siddiqui has worked with many ethnic groups in the city and through this experience she realized that the stereotypes of First Nations from western movies were as pervasive as stereotypes of Muslims in Canada – and that the only way to combat them was to open a dialogue. At first, when the Maclean’s article came out, she was apprehensive of the controversial statement it made. “But then I realized that this is an important conversation to have.”

“Accepting a person for who they are and what they are, that can only happen if you have face to face conversation… when you share your stories, when your children play together, when you stand up for each other.” – Shahina Siddiqui, Islamic Social Services Association

Champagne’s reaction was more immediate. “One of my takeaways was relief, that finally we were having this conversation.”

For Siddiqui, the development of community is essential. She says that because newcomers and Aboriginal people have so much in common coming from colonized experiences, it is important to understand and share that.

“Accepting a person for who they are and what they are, that can only happen if you have face to face conversation… when you share your stories, when your children play together, when you stand up for each other.”

With this idea in mind, ISSA runs Conversation Cafes with several of the ethnic and Aboriginal groups in the city, focusing on sharing tradition and histories one on one. Other groups in Winnipeg have begun similar programs with the same goal. Manitoba Educators for Social Justice (MESJ), a group of concerned educators from across the province, hosted its first Salon in which they discussed new strategies to address racism.

“While we share so much in common we also have to look at our own biases, because I think together we are stronger.” – Shahina Siddiqui, Islamic Social Services Association

Kelly Reimer, one of the founding educators of MESJ, has implemented after-school programs at his downtown Winnipeg school that encourages this type of sharing.

“About once a month we have members of the community that come in and we celebrate a particular group of students that we have at our school, it could be South Sudanese or Filipino,” he says. “We have food, a cultural display and a discussion that attracts 100 to 200 people.”

The shared histories and struggles of newcomers and Aboriginal people can help to forge stronger community bonds.

“While we share so much in common we also have to look at our own biases,” says Siddiqui, “because I think together we are stronger.”

This is the final instalment in a special three-part investigative series our NCM 360° reporting team put together. See Part 1 and Part 2 for a full picture of what’s happening in Winnipeg.