Near the middle of the Toronto Necropolis, one of the city’s historic cemeteries, visitors might run into an august headstone with “Blackburn” engraved on it. It marks the grave of Thornton Blackburn, who was a prominent abolitionist and the founder of Toronto’s first taxi company before his death in 1890. But his journey toward becoming a pillar of Toronto’s community was not an easy one.

Blackburn, just like his wife Lucie (born Ruthie), was born into slavery in the United States. Together, much like thousands of slaves like them yearning to breathe free, they escaped using the Underground Railroad. They were able to enter Canada due in large part to a lack of immigration law, and built a strong and close-knit community in Toronto.

When the Blackburns arrived in Toronto, the African Canadian community had been there since European colonization. Black slaves were present in New France, and the system was continued after the French defeat by the British in the Seven Years War. Colonists brought over their slaves as they settled the northern shore of Lake Ontario, what was then called York and is now Toronto. It should be noted, though, that the majority of slaves in Canada were of Indigenous background.

Toronto’s Black population in 1800s

Across the street from where St. Lawrence Market is now there used to be a flat open-air market. It is not known how common the practice was at this location, but slaves were sold there according to Eric Wilfred Hounsom, author of Toronto in 1810. “Auction sales and public meetings were also held at the market, including the occasional auction of a negro slave,” Hounsom writes in his book. Free Blacks were living in York as early as 1799. Some of them were relied upon as road builders.

That isn’t to say that slavery was widely approved of. The first Lieutenant-Governor of Upper Canada, of which York was the capital, John Graves Simcoe, saw slavery as a moral evil offensive to his Christian beliefs. Spurred on by the Chloe Cooley incident, he attempted to abolish the institution with the Act Against Slavery pretty much as soon as he arrived in York in 1793. He was forced to compromise his stance after considerable pushback from his fellow aristocrats, who were slave owners. The law prevented further importation of slaves and stated that the children of slaves could attain freedom at age 25. This way, slavery was gradually abolished in Upper Canada.

It is hard to accurately establish how many African Canadians lived in Toronto throughout the 1800s, but there are some clues. As Henry Scadding wrote in his 1873 book, Toronto of Old, “The negro population was small. Every individual of colour was recognizable at sight. Black Joe and Whistling Jack were two notabilities; both of them negroes of African birth.” Scadding moved to York in 1821, and his account is one of the best sources on the era.

The first census of the city’s Black population, which happened in 1840, showed there were 525 Black people living in Toronto at the time. The population appears to have peaked in 1850 at 1,000, but that number soon halved due to outmigration to the U.S. The population was 468 in 1911 and 1,236 in 1921.

The Blackburns’ escape

Thornton Blackburn and his wife Lucie decided to escape their Louisville, Kentucky, captors in 1831, using forged freedom papers (documents declaring their free status), after they discovered Lucie was going to be sold. They made their way north via the Ohio River and settled in Detroit, where they became well-liked pillars of the local Black community, as historian and archeologist Karolyn Smardz Frost writes in her biography of the Blackburns, I’ve got a Home in Glory Land.

But the good times did not last. That same year, Thornton ran into an associate of his former owner, who gave away the Blackburns’ whereabouts. In June of 1833, the couple was arrested by the sheriff of Detroit. The community of free Blacks did not stand for this, and a plan was hatched to release them.

Using a trick, they were able to sneak Lucie out of the jail and take her to Upper Canada. But to rescue Thornton, they staged what became known as the Blackburn Riots and busted him out of jail the day after Lucie was sprung. They spirited him away across the Detroit River, the border between the U.S. and Canada back then and today, into what is now Windsor, Ont., where Lucie was waiting for him.

Thornton was rearrested on the Canadian side; during his daring escape, he had pulled a gun on the sheriff of Detroit. His former owners saw this as a pathway to extradition and re-enslavement, but after a lengthy trial, Thornton Blackburn was allowed to stay in Canada. The couple then settled in 1834 in Toronto, where Thornton’s brother, Alfred, lived.

The Underground Railroad refugees

Karolyn Smardz Frost very deliberately refers to escaped slaves arriving in Canada as refugees.

Karolyn Smardz Frost very deliberately refers to escaped slaves arriving in Canada as refugees.

“Their way was smoothed by the fact, first of all, that Simcoe and the Chloe Cooley Incident gave governor Simcoe the political capital to create the first anti-importation law against slavery in the British Empire,” Smardz Frost told NCM.

Attorney General of Upper Canada in 1819, John Beverley Robinson, “refused to allow American slave catchers into Canada to chase their prey and said basically that once they reached Canadian soil they were going to be free,” Smardz Frost said. “He confirmed the idea that there was no slave importation. That meant the door was open for the Underground Railroad refugees to come to Canada.”

Upper Canada’s immigration policy at the time of the Underground Railroad was to have no laws that governed who came to Canada. The first law would not come into force until 1869, after the abolition of slavery in the United States. But even then, it had few, if any, restrictions on who could come to Canada. It was more of a document restricting trade.

“Canada and the United States were anxious for settlers to fill that land up, not that they should be filling up the land that belonged to the First Nations peoples. But that was their attitude,” Smardz Frost added.

“If you wandered across the border, the only thing you would see was a customs agent to make sure you weren’t importing goods without paying duty on them. They were concerned about customs duties, not about people.”

Days of prosperity

The Toronto society that the Blackburns and people like them entered was a mixed bag. Some Black Canadians prospered while others struggled. Some were tradespeople, some were menial labourers and others, usually women, were domestic servants. Thornton often worked as a waiter at Osgoode Hall, now the seat of the Law Society of Upper Canada.

Inspired by a cab company in Montreal, the Blackburns founded Toronto’s first taxi company—despite being illiterate. Called “The City,” the company became successful and iconic. The Toronto Transit Commission even adopted the same red and yellow colour scheme for an early version of its streetcars.

The couple would go on to dedicate themselves to becoming ardent abolitionists. They provided room and board to newly arrived fugitive slaves near their home on 54 Eastern Ave. The property is now long gone. In its place is the Inglenook Community School, where Smardz Frost led an archeological dig in the 1980s.

Toronto’s racist legacy

While there were many white Canadians who welcomed new Black Canadians, racism was rampant in the city. After the end of the American Civil War, former president of the Confederate States of America, Jefferson Davis, paid a visit to Toronto. A news article from the era says that he was “enthusiastically cheered by a large crowd.”

Smardz Frost’s own book quotes Lord Elgin, former Lieutenant-Governor of Upper Canada, as saying he did not want his jurisdiction to be “flooded with blackies who are rushing across the frontier to escape from the bloodhounds whom the fugitive slave bill has set loose on their track.”

She also quotes opinions expressed in newspapers by “ordinary” whites. “People may talk about the horrors of slavery as much as they choose; but fugitive slaves are by no means a desirable class of immigrants for Canada, especially when they come in large numbers,” one unnamed individual wrote to a newspaper.

Sadly, racism in Canada is far from ended. Groups like Black Lives Matter are raising awareness about Black marginalization in Canada, the seeds of which were laid in the slavery era.

But the lack of immigration law in Canada did give some Black Canadians a fighting chance for prosperity, even if the odds were stacked against them.

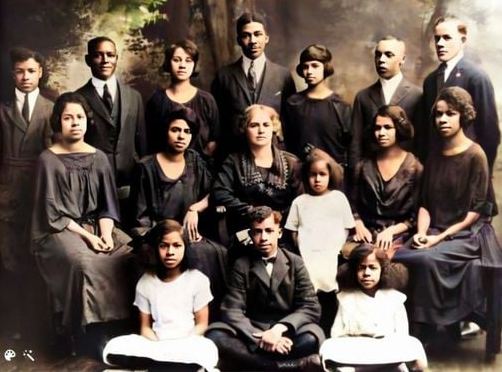

Rob Green’s proud family history

Musician, actor and former teacher, Rob Green, 70, currently lives in Hamilton, Ont., but his family has deep roots in Owen Sound thanks to the Underground Railroad. “It was always a hush hush type of thing. But every once in a while stories would come out,” Green told NCM.

The bulk of what Green learned about his family’s ties with the Underground Railroad was discovered in his adult life when he began investigating it himself.

He is fifth generation Black Canadian, descended from Elias Earlls of Kentucky and John Green from Maryland. Both men came to Canada through the Underground Railroad, and Rob Green believes that John may have been helped by the legendary figure Harriet Tubman. A third branch of the family tree, the Woods, was created when a white woman named Sarah married into the Elias Earlls side of the family.

The discovery of these names has filled Green’s family with pride. His first cousin, Pamella Houston, is an office administrator with the Ontario Black History Society and is heavily involved in Black History programming for this year.

Green believes in the old adage: “If you know where you came from, you know where you are going. We are so gifted. We have such a large family and a large family tree. We are so gifted with the early black pioneers who paved the way for us.”

Mansoor Tanweer is New Canadian Media’s Local Journalism Initiative reporter on immigration policy. An immigrant himself, he has covered municipal affairs and the Brampton City Council in addition to issues relating to newcomers over several years.

Informative and timely articles. Brought back memories told to me by my Lawson family members who arrived in the Queens Bush Canada via the Underground Railway.