Twenty years ago, the British/South Asian comedy show, Goodness Gracious Me, ran a skit where a British employee at an Indian firm needed to change his name from Jonathan because it was deemed too foreign and hard to pronounce. Behind the parody was the fact that South Asians in Britain often felt they needed to adopt English names to succeed.

At that time, globalization was seen as a result of the increasing influence of Western culture and ideas across the globe. The East needed to adapt to the West. Twenty years later, after a global financial crisis, that power equation has shifted.

Growing Chinese Influence on Business

Those working in Canada’s resources sector have long been conscious of the East’s power (specifically China’s) as their fortunes are often tied to it. For many of us working in Canada’s marketing services, however the reality of our global situation was brought into sharp focus by the recent acquisition of Cossette Communications’ parent company by China’s BlueFocus Communications

[I]t is hard to see how the nature and impact of China’s business culture will evolve as the country interacts with the world in its new more diverse and influential role.

As China’s influence on business in Canada and the world grows, our success becomes more dependent on a need to understand China’s business culture. The West has gained much of its early understanding of Chinese business culture not from working with the vast population of mainland China, but from Hong Kong, Singapore and Taiwan, as well as the Chinese diaspora.

Of course, our learning has increased, as China rapidly entered the global economy over the last 20 years. But this has provided the West a specific view of China and Chinese businesses primarily in the role of a lender, a consumer of resources and a vast network of producers – all often entangled with the bureaucracy of the state. From that angle, it is hard to see how the nature and impact of China’s business culture will evolve as the country interacts with the world in its new more diverse and influential role.

Business Culture and Ethnic Culture

Ethnic culture differs from a company’s business culture, but has an influence on the way business is conducted. For this reason, it makes sense to look at how China’s ethnic culture may differ from other nations.

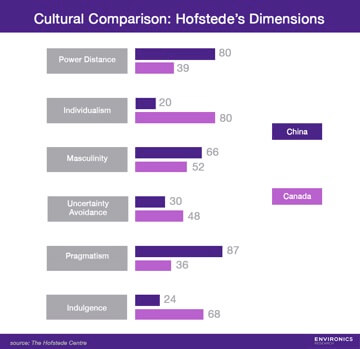

Our own research at Environics has shown the differences between the Chinese and Canadian cultures. One of the most widely used tools, developed by Geert Hofstede, shows how Chinese culture differs from Canadian culture on six primary dimensions

Canada, in line with much of what is called “the West,” is more individualistic than collectivist China (see chart). China tends to be more hierarchical compared to the more egalitarian Canada (see “power-distance” on chart), as well as more pragmatic.

Canada, in line with much of what is called “the West,” is more individualistic than collectivist China (see chart). China tends to be more hierarchical compared to the more egalitarian Canada (see “power-distance” on chart), as well as more pragmatic.

So, on a practical level, what do those working with Chinese companies need to be aware of to have a successful relationship?

Chinese “Pragmatism”

One aspect of Chinese culture that we already see impacting business culture is what Hofstede calls “pragmatism.” He says that, “In societies with a pragmatic orientation, people believe that truth depends very much on situation, context and time. They show an ability to adapt traditions easily to changed conditions.”

Many in the West attribute China’s manufacturing success to low costs, especially of labour, but that is not all that lies behind Chinese manufacturers’ ability to shift quickly depending on their circumstances. The ability of Chinese manufacturers to respond quickly, for example, to Steve Jobs’ sudden demand for an unscratchable glass iPhone screen has become part of business lore. Behind this agility are a number of factors and important among them is the Chinese position on the pragmatic cultural dimension.

Cultural Characteristics Impact Business

Generally, a result of this cultural characteristic is the perspective that each situation needs to be evaluated independently from accepted rules. Just because one rule has worked in the past doesn’t mean it should apply now. For rule-oriented Canadian businesses, that can cause tensions. It can even raise complaints about a lack of integrity or at least fairness, just as some of the American manufacturers who watched their Chinese competitors pivot to produce iPhone glass screens surely thought that’s not fair – they’re not following the rules.

And this is one area where we will find the seeds of progress that the interaction between these two cultures create; the combination of best business practices developed in the West with Chinese pragmatism and the business agility it fosters.

That is not to imply that Chinese businesses are not interested in learning and, if appropriate, following the best practices that have been developed in the West. This is where we suspect we will find the seeds of progress that the interaction between these two cultures create; the leveraging of best practices developed over years of experience in an agile manner. The fact that Chinese business culture has been born into a highly dynamic market will likely contribute to the country’s “pragmatic” cultural character as well as its ethnicity. China can embrace new approaches more easily without the pain of wrestling with the past, just as consumers in developing markets have “leap frogged” the West in adoption of mobile and digital technologies.

The interaction between Chinese pragmatism and Western business protocols will cause conflict. We have seen it in our own experience. Overcoming that conflict is of course important to those involved. The key for both Western and Chinese businesses to prosper side by side is to take the cultural diversity and even the conflict that it might generate and turn it into progress. And this is one area where we will find the seeds of progress that the interaction between these two cultures create; the combination of best business practices developed in the West with Chinese pragmatism and the business agility it fosters.

Individualist Canada versus Collectivist China

The difference between an individualist outlook and a collectivist outlook creates an enormous amount of cultural tension and misunderstanding. Individualism values one person standing up, with a loud voice and doing his or her own thing. Collectivism values working together within an accepted set of protocols with an eye on the collective goals.

Cultural differences, if understood and managed well, are seeds to progress.

As Western companies have expanded outside of their domestic markets, they have encouraged an individualistic business culture. The assumption in the West is that individualism fosters creativity and allows the brightest to shine and be rewarded. As China’s influence expands, Chinese businesses will carry their collectivist ethnic culture with them. Will that create conflicts and misunderstandings just like it did when Japan’s influence extended across the globe? It likely will. But tension can be fertile soil for progress. And the West should be open to the notion that individualist values are not always superior.

A recent experiment into creativity led by Dr. Gad Saad of Concordia University attempted to test the difference between the way collectivist and individualist cultures generate ideas. What it found implied that individualist cultures were more creative in that they did indeed generate more ideas. But collectivist cultures, where the group focuses on perfecting ideas, generated fewer, but better, ideas. Again, we see opportunities for progress in the interaction between these two cultural modes. It may be simplistic, but if individualism generates more ideas and collectivism creates better ideas, we can manage the interaction between cultures to generate more and better ideas!

Cultural differences, if understood and managed well, are seeds to progress. Some of the greatest ideas of human history have been born from cultural tensions, often developed from commercial interactions. As cultures mingled and clashed in the trading cities on the fringes of the Roman Empire or the colonial outposts during the spice trade era, powerful new ideas and ways of looking at the world were born. Now opportunities to build new ideas through the interaction of distinct cultures are emerging as the influence of the East rises. The future belongs to those in both the East and the West who can develop the “transcultural competence” to take full advantage of them.

Robin Brown is Senior Vice-President, Consumer Insights and Kathy Cheng is Vice-President, Cultural Markets Research at Environics Research Group, a research and consulting firm. They are the authors of Migration Nation, A Practical Guide to Doing Business if Globalized Canada.

Robin Brown is Senior Vice-President, Consumer Insights and Kathy Cheng is Vice-President, Cultural Markets Research at Environics Research Group, a research and consulting firm. They are the authors of Migration Nation, A Practical Guide to Doing Business if Globalized Canada.