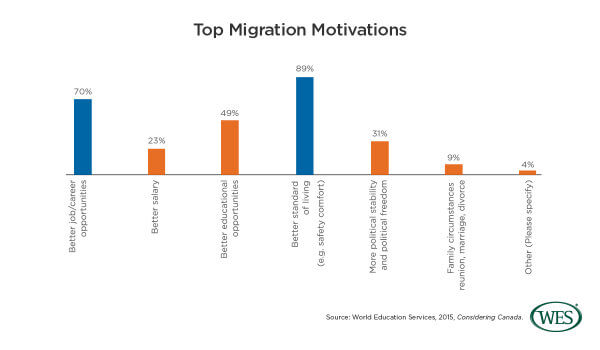

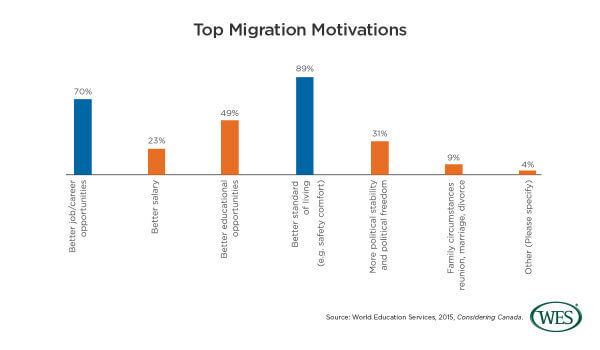

Even more than career prospects, the perceived high quality of life is at the top of the list of what motivates skilled professionals in countries like India, China and the Philippines to consider applying for immigration to Canada.

This is according to recently released data from the World Education Services (WES), in a report titled “Considering Canada: A Look at the Views of Prospective Skilled Immigrants.”

Over 3,000 respondents completed a survey WES administered to individuals considering applying to Canada – primarily those living overseas. As one of several agencies that Citizenship and Immigration Canada (CIC) designated to provide educational credential assessments (ECA) to be used as part of the new immigrant application process introduced in 2012, the organization had access to this population.

Vinitha Gengatharan, director of international relations at University of Toronto and chair of the board of directors for Agincourt Community Services Association, says this type of information is crucial to know if Canada is to remain relevant in an increasingly competitive global landscape.

Aside from demographic information and examining the motivations of prospective skilled immigrants, “Considering Canada” also takes a look at what the perceived barriers this group of people expects to face upon arriving in Canada, if successful.

“There is a competition for skilled immigrants all over the world —everybody wants them,” says Gengatharan, whose family arrived in Canada from Sri Lanka 30 years ago. “What are they looking for when they decide to immigrate, and what can Canada offer? What can we do to be more competitive in that space . . . to be an attractive destination, is why it’s important to reach out to this audience. How can we be proactive in meeting their needs?”

In the months leading up to the report’s official release, Timothy Owen, director of WES Canada, presented some of its key findings at conferences throughout the country. He says the fact that prospective immigrants place high value on Canada’s standard of living is something he made a point of highlighting to the various stakeholders he presents to – academics, government officials, community service providers and regulatory bodies.

“I think that kind of spoke to — for me anyways — Canada being seen as a good place to live and to bring up your family, and while career prospects were a very important part of the decision to come to Canada, maybe this lifestyle was one of the driving factors and motivators.”

A Younger, More Educated Candidate Pool

“Considering Canada”also highlights changing demographics amongst those now considering migration to Canada. The candidate pool appears to be younger, and also more educated.

What the report shows is that within the ECA applicants WES surveyed, nearly 95 per cent fell within the 25- to 44-year-old bracket, and only three per cent in the 45- to 64-year-old one. This is in comparison to data released by CIC in 2013 about landed immigrant applicants that showed 84 per cent were 25 to 44 years old.

Owen says that one of WES’s goals following the release of the report is to look at ways to create services that help skilled immigrants learn how to transfer their skills to similar lines of work, instead of resorting to “survival jobs.”

Furthermore, nearly all of the applicants held a degree; 40 per cent had a master’s degree or higher. This is up from previous reports from CIC, which indicated a smaller percentage (only around 18 per cent with a master’s degree) of applicants in 2012/2013 were that highly educated.

This raises the question of why the demographics have changed. Owen has one hypothesis.

“I think part of it could have been that it was taking a long time in the old immigration system for people to get processed and arriving in Canada after they made their application, and so maybe some of the people who were best qualified found other opportunities somewhere else,” he explains. “That’s a possibility, but now, with the Express Entry program, I know the goal is to speed up the processing of people.”

What Comes Next

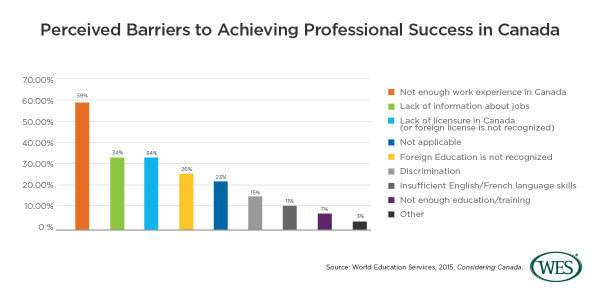

Aside from demographic information and examining the motivations of prospective skilled immigrants, “Considering Canada” also takes a look at what the perceived barriers this group of people expects to face upon arriving in Canada, if successful.

Even more interesting: depending on a person’s native country, their outlook on Canadian career prospects varied. At 26 percent, Chinese respondents had an overwhelmingly more negative view of job opportunities in Canada, in comparison to their Indian and Filipino counterparts, of which only one per cent and two per cent indicated negative outlooks, respectively.

And while not enough Canadian experience was listed by 59 per cent of respondents as the number-one barrier, Owen says this remains an overwhelming frustration amongst people who eventually end up fulfilling the application process and arriving in Canada.

“How do you get Canadian experience if you can’t get a job in Canada?” is a common question he says WES research consultants encountered during recent research with focus groups of respondents who are now in the country. “And people are frustrated that their experience from their home country isn’t valued as highly as they thought it would be. That’s probably the biggest surprise to people.”

Owen says that one of WES’s goals following the release of the report is to look at ways to create services that help skilled immigrants learn how to transfer their skills to similar lines of work, instead of resorting to “survival jobs.”

This is something Gengatharan can appreciate: her dad worked for one year as a security guard upon arrival in Canada, before eventually gaining employment in a position more closely related to his land-surveyor profession.

“I know so many people [working “survival jobs”], that’s how they gain their Canadian experience; I feel like in a globalized world a lot of experiences can be transferable,” she says, adding it still remains unclear exactly what is accepted as “Canadian experience.”

Lack of information about jobs, and lack of licensure or foreign licences not being recognized in Canada were tied at second place for the most anticipated barriers, while discrimination, insufficient English/French language skills and not enough education/training ranked fairly low on the list.

Even more interesting: depending on a person’s native country, their outlook on Canadian career prospects varied. At 26 percent, Chinese respondents had an overwhelmingly more negative view of job opportunities in Canada, in comparison to their Indian and Filipino counterparts, of which only one per cent and two per cent indicated negative outlooks, respectively.

Owen says WES aims to present this report to community agencies, academics and government and regulatory bodies to hopefully ensure a better-informed approach to service provision for prospective immigrants – particularly while they are still overseas.

This is something the Christine Nielsen, chief executive officer at the Canadian Society for Medical Laboratory Science (CSMLS), says her organization is greatly in support of. A national certifying body that has been using WES’s ECA as part of its prior learning assessments for the last five years, the CSMLS sees around 300 people each year looking to come to Canada to work in the medical lab profession.

Nielsen says her organization does much of its assessment work while the clients are still overseas, and she would like to see more regulatory bodies follow suit.

“If you have no chance of practising your profession, or it’s going to take years for you to practise your profession, every immigrant I’ve talked to wants to know that information before they come and how long or how slow the process is going to be, and they can make the best decision for their families.”

There is also no dearth of research studies being conducted by academics and organizations across the country relevant to new Canadians. Research Watch will keep an eye on the studies being released and uncover key findings on a regular basis. Conducting research that you think would be of interest? E-mail us at [email protected].