Toronto City Council is heralding its latest election as an accomplishment of equity, diversity and inclusion, but a former city staffer wants Torontonians to remain critical of its government’s claims of success.

Assistant professor at Toronto Metropolitan University Shana Almeida was the only racialized chief of staff working at city hall in the early 2000s.

Her latest book, Toronto the Good?, launched Nov. 16, is an archive dig of how municipal politicians have dealt with claims of racism from 1975-2018.

“I was the only one talking about race and racism,” said Almeida, who left politics for academia in 2009 after almost a decade.

“So I couched it in ‘diversity’ language. Whatever policies we passed on race it was because I never named it.”

Almeida’s research is a critical take on the way municipal politicians handle accusations of racism, and highlights how recycling equity committees and consultations conceal a deeper systemic issue.

“When we say diversity, we mean people who are not white,” says Almeida, noting that simply adding more racialized players to the game does not automatically translate into more diverse or progressive resolutions.

She says access to generational wealth and knowledge of how municipal councils work have for a long time been privileges available to a few. That has resulted in the exclusion of many people from diverse socio-economic backgrounds from even entering a political race.

Etobicoke-Lakeshore’s new councillor Amber Morley says that’s even harder for racialized people.

“For folks from the margins who are focused on survival and having the resources to live day to day in an incredibly expensive city, financing a campaign has additional hurdles to overcome,” Morley said.

Municipal election campaigns can cost tens of thousands of dollars, according to Ontario’s financing regulations.

Morley says for single-income earners, transit riders, renters, and newcomers, financing campaigns in wards that are now double the size they were before 2018 means more sacrifice and people needed to run them.

Political interference

Out of 163 candidates who ran for councillor in Toronto’s latest municipal election, nine overturned their ward’s incumbent, most of whom tout over a decade of service in office.

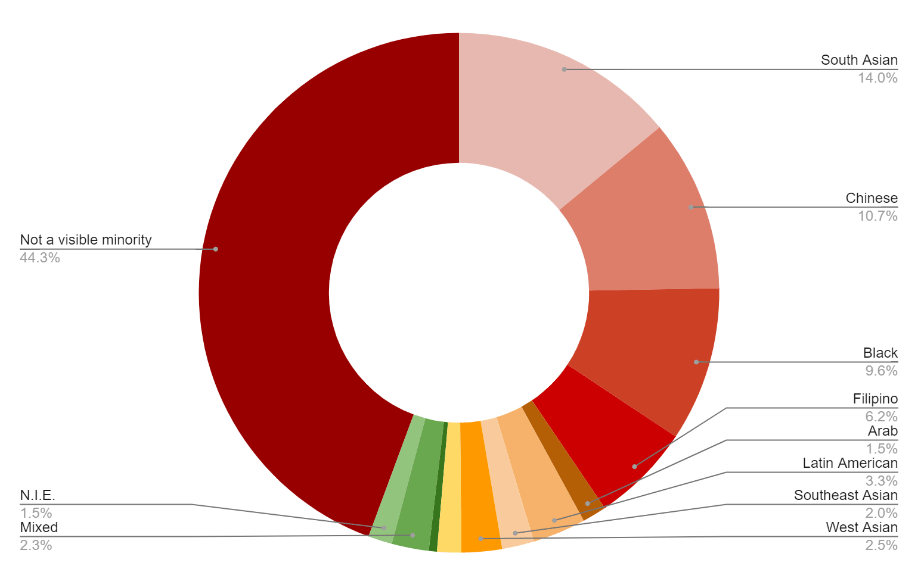

A third of City Council, officially seated since Tuesday, come from some of Toronto’s most diverse communities, given that 55 per cent of the city’s population is racialized.

“Diversity in leadership doesn’t have value if it doesn’t commit to being with and for people who have been socially and economically excluded,” Davenport’s new councillor Alejandra Bravo, said.

Bravo, who has run for office at the municipal level four times, including this past race, and once in federal elections, says that political interference has also been a factor tipping the scales against these communities.

“In 2018, we were on track to elect an historic number of women, of racialized people, immigrants or from immigrant families,” Bravo said, referring to the last election season when Ontario’s Premier Doug Ford invoked the notwithstanding clause to ram through legislation that ended up cutting city council wards down from 47 to 25.

Bravo says the move deferred change. Ward boundaries changed either eliminating or making it twice as difficult to finance campaigns for candidates like Morley and Ausma Malik, both of whom returned this year and won.

“You see that sustained commitment over time around an agenda generated out of the struggles and experiences of people and other allied organizations on the ground,” she said.

From grassroots organizing

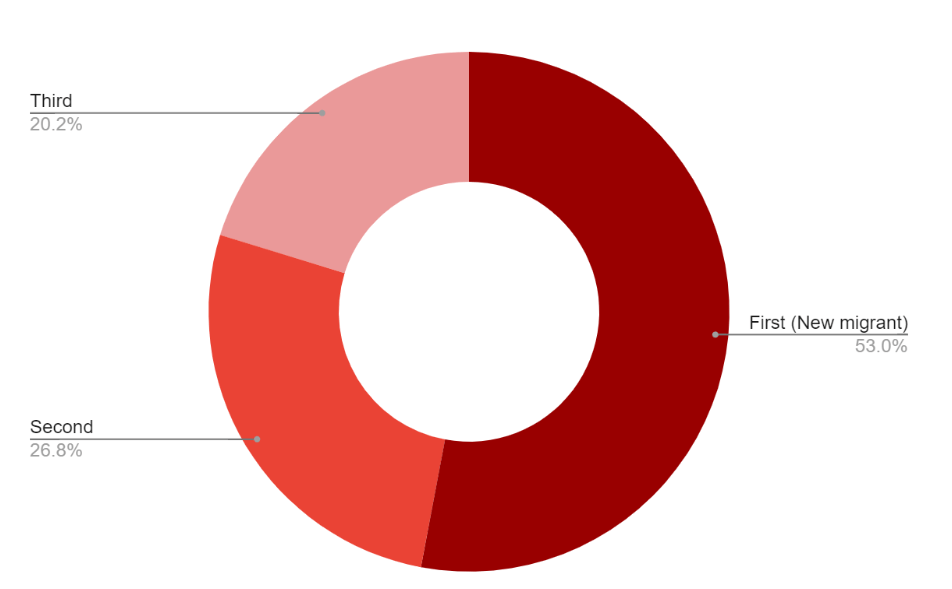

Scarborough-North’s newly-elected councillor Jamaal Myers — a second-generation immigrant — says he knows all too well the barriers that newcomers face, from financial instability to social stigma.

Having grown up in Scarborough, Myers says living in community housing with a single-income family, seeing peers priced out of their homes, and time living in rooming houses as a university student has not only influenced his politics but helped him get close to his community.

“I have that perspective of seeing just how many roadblocks the government puts in place to prevent working people from leaving Toronto Community Housing,” he said. “It’s just bringing that perspective to the decision-making table.”

During the campaign, Myers was supported by grassroots organization Progress Toronto, along with what the nonprofit calls its “Progressive Champions,” including Morley and Bravo — who is the advocacy group’s cofounder — Malik and Chris Moise.

Progress Toronto supported campaigns committed to tackling affordable housing, accessible public transit, the city’s continuing responsibilities to Indigenous people; humane conditions for the city’s unhoused population; employment; police violence, and more. It also helped alleviate the financial burden and lack of personnel some of these candidates faced in order to even the political playing field.

“Our theory of change is to demystify municipal politics and push for further inclusion all year round,” said Saman Tabasinejad, a spokesperson for Progress Toronto who makes regular appearances on CBC’s The Conversation.

The nonprofit looks at the intersections between wealth, race and power, as BIPOC living in Toronto continue to face barriers accessing working transit and affordable housing, are disproportionately affected by police violence, and deal with daily experiences of racism.

“There are intersecting positionalities that reflect how people move through this city, understand this city and reflect the communities we come from,” Tabasinejad said.

Deena Ladd, the executive director of the Workers Action Centre, says it’s not enough that candidates be racialized but that they have vital lived experiences and grassroots involvement with their communities.

“It’s not just skin-deep,” she said, pointing to the need for ideological diversity on municipal councils. “It’s about the experience they bring to the table.”

Ladd says diverse lived experiences settling into Toronto will help new councillors understand what immigrants and refugees, or working people living in poverty are going through.

“Grassroots organizing shows that it’s not just about winning an election, but about supporting your community,” she said.

Other new, progressive councillors include Ward 10 Councillor Ausma Malik, who overturned Spadina-Fort York’s incumbent Joe Mihevc, and is the first hijabi-wearing Muslim woman elected to council in the history of Toronto municipal office.

Ward 13’s Councillor Chris Moise, Toronto’s first LGBTQ+, Black man elected to council, overturned Toronto Centre’s Robin Buxton Potts.

And University-Rosedale’s Dianne Saxe overturned Mike Layton, who had served on council since 2010. Saxe was not a progressive champion with Progress Toronto, but aligned in political views on the welfare of unhoused populations in Toronto and meeting the city’s zero-impact climate commitments.

____________________________________________________________________

**According to TRC recommendation #93: this piece was collaborated and published on “Treaty 13” Territory, Tkaronto (Scarborough) and “Treaty 19” Territory (Brampton); un-ceded lands of Musqueam, Squamish, or Tsleil-Waututh Peoples, Vancouver; un-ceded Anishinabe Algonquin territory, Ottawa.

This article has been updated to correct the number of election races Alejandro Bravo has run at various levels of government.

Keitlyn (they/them) is a multi-media journalist residing in Scarborough, Ont. They are interested in long-form journalism that highlights the visibility of BIPOC expression. True to millennial form, they are a small business owner, carpenter and freelance photographer. They were interested in NCM as it understands the "big picture." Journalists are dedicated to truth and democracy. Our communities have not always had access to these privileges. NCM is filling in a large gap that North American media has long neglected.

Fernando Arce is a Toronto-based independent journalist originally from Ecuador. He is a co-founder and editor of The Grind, a free local news and arts print publication, as well as an NCM-CAJ member and mentor. He writes in English and Spanish, and has reported from various locations across Canada, Ecuador and Venezuela. While his work in journalism is dedicated to democratizing information and making it accessible across the board, he spends most of his free time hiking with his three huskies: Aquiles, Picasso and Iris. He has a BA in Political Science from York University and an MA in Journalism from Western University.