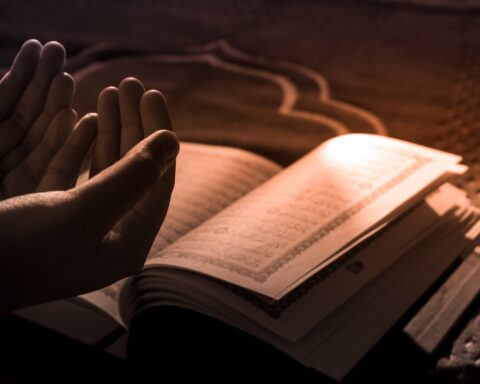

I’m a Canadian Muslim — proud of my faith. I feel privileged to be counted among those who share a belief system that has brought spiritual fulfillment, purpose and meaning to billions over the past 1,400 years. I feel that my Canadian identity is also an integral part of who I am.

As with any major faith, Islam has a myriad number of interpretations, sects, denominations and schools of thought. We have our ‘saints’ … our ‘satans’ as well.

The issue of identity lies at the core of every individual’s journey of self-discovery and self-realization. While many want to ‘fit in’ and be accepted into the society in which we’ve been raised, we also feel a yearning to connect with our roots, our heritage and the culture of our ancestors. For many Muslims in the West, the balance between the freedom to express one’s personal identity and the need to be accepted by parents who come from another time and culture can be precarious.

Many cultural factors influence how we behave — and religion is interpreted as reflection of the culture in which it is observed, not the other way around.

When I heard of the massacre in Orlando and learned something about the background of the gunman, I knew — before hearing any details — what the story was about. The young man evidently was struggling with a conflicted sense of identity. He was, apparently, gay himself. He felt ashamed of who he was and struggled to reconcile the conflicting — yet undiscussed — duplicity inherent in the ultraconservative religious culture of his family’s native Afghanistan.

His religious or political views may have had nothing to do with the tragedy; the professed vehement homophobia of his family’s culture most certainly did. When the father claimed that he was shocked by his son’s appalling act of violence, it was apparent to me that he — like too many other parents — had ignored how his son’s self-hatred had been the catalyst for his so-called “radicalization”.

It’s important to separate Islam, the faith, from the tribal systems that tend to be intertwined with it — tribal systems which consider their particular culture and habits to be indistinguishable from Islam itself. (It’s really not much different from the case of Americans affiliated with the Ku Klux Klan who consider their world-view and ideology as vital parts of their ‘Christian’ identity.)

I have witnessed several cases of young men coming from the same background as Mateen who had homosexual inclinations — young men who came from families that publically supported extremist groups, spewed anti-Western rhetoric online, in public and in the community, and supported extremist interpretations of Islam that embrace the execution of homosexuals, rampant misogyny and other self-destructive and violent forms of behaviour.

Rather than supporting generalizations against all Muslims, we should treat the various manifestations of violent extremism as we would any other mental health problem or crime

These families espoused these views because of the tensions created by the clash between their native cultures and their adopted one. Luckily for those young men, they learned to reconcile their religious identity with a candid assessment of their cultural identity, helping them divert themselves from the sort of mental and psychological breakdown that might have led them to violence.

Many cultural factors influence how we behave — and religion is interpreted as reflection of the culture in which it is observed, not the other way around. Most known extremists and terrorists are anything but spiritual and devout individuals. They tend to be broken people — empty shells with weak personalities and low self-esteem, carrying emotional baggage from childhood, from growing up in unbalanced families.

So what’s the solution? Rather than supporting generalizations against all Muslims, we should treat the various manifestations of violent extremism as we would any other mental health problem or crime. Steps should be taken to train and equip parents to recognize signs of mental illness, as well as the subtleties of unstable behaviour patterns, and to take the proper measures to have their child’s condition diagnosed and treated.

Fearmongering and victimization are counterproductive — they amount to sticking our heads in the sand regarding the effect of cultural pressures and alienation. Recognizing the influences of the various cultures from which we come can circumvent the development of more fringe psychotics and prevent future acts of heinous violence.

On that note, I would like to add that the “scholar from Iran” who spoke at a mosque outside Orlando about three months ago — who described the “killing of homosexuals” an act of “compassion” — is someone whose views are deeply disturbing to me, especially considering the cool, calm way he talks about mass murder. I would say his demeanor reminds me more of the killer in Alfred Hitchcock’s’ Psycho than of any learned Islamic scholar.

Republished in partnership with iPolitics.ca