“If you know all the languages of the world and you do not know your mother tongue or the language of your culture, that is self-enslavement. Knowing your mother tongue and all languages is empowerment.”

Those are the words of Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o, a Kenyan writer, academic, novelist and author of the well-known book “Decolonizing the mind.“

Thiong’o focuses on the loss of mother tongues in lands that have been colonized and the further loss of mother tongues when colonized people leave their motherlands and lose their languages in a new country.

While Thiongó is not against colonial languages, especially English and French, he claims that losing one’s own mother tongue significantly contributes to part of the process of enslavement.

One of the main issues for immigrants is losing their mother tongues while in Canada.

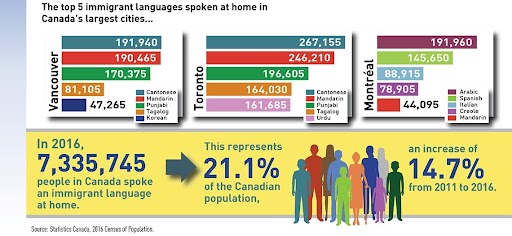

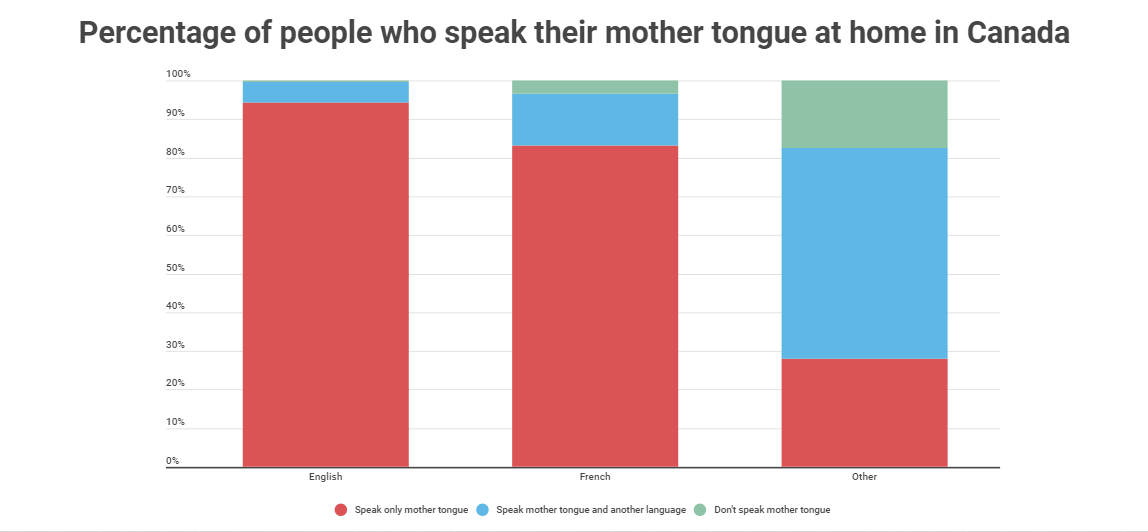

According to the 2016 Census, almost 7.6 million Canadians reported speaking a language other than their mother tongue at home.

Speaking a language other than one’s mother tongue at home decreases fluency in the language because people have fewer chances to use their native languages outside of their homes.

Jaffer Sheyholislami, who teaches linguistics and language studies at Carleton University, says the majority of children from newcomer families in Canada generally speak mostly English or French at home. This is especially true with respect to the second generation. By the third generation, usually, the ancestral language is lost.

In an interview with New Canadian Media, Sheyholislami said: “One of the important causes of language shift and loss in Canada is the absence of robust language policies that would advocate and actively promote and support multilingualism and multiculturalism, especially when it comes to double minorities such as the Kurds.”

Australian National University (ANU) published a study on Global predictors of language endangerment and the future of linguistic diversity which reveals that many of the world’s languages are in danger of dying out.

This “extinction debt” is due to a reduction in intergenerational transmission over time. In other words, extinction debt occurs when languages that are currently spoken by adults are not learned as a first language by children.

The ANU researcher found that without immediate intervention, language loss could triple in the next 40 years. And by the end of this century, 90 per cent of the world’s languages — or 1,500 of them — could cease to be spoken.

Fear of losing mother tongue

Many Canadian parents and families who come from different geographic backgrounds are worried about themselves or their children losing their mother tongue.

Nancy Moinde is a researcher at Simon Fraser University and a mother of two sons who came to Canada from Kenya many years ago. Moinde told NCM that before her children were born, she discussed with her husband about teaching their children Kiswahili. Unfortunately, it did not turn out that way after they eventually moved to Canada.

Sheyholislami believes families and parents are afraid that their children may lose more than just their mother tongue. They worry about their children losing connections with their parents’ culture, their sense of identity, their families living back home and their homeland in general.

“A diasporic person, especially those of the first generation, always dream of returning ‘home’ one day but not without their children. If that happens, it must be in the language of ‘home,’ otherwise there will not be enough connections to have a happy return.”

In 2011, Moinde took her children to Kenya while they had been exposed to more Kiswahili through their formal education and also, to some extent, their social lives with friends and family — they were far from fluent in speaking it.

“I had made it a habit of intentionally integrating different words in Kiswahili while describing or naming something in my English sentences,” Moinde said.

“Despite my inconsistent attempts to encourage them to speak Kiswahili, I never heard them actively speak a whole sentence of the language unless prompted.”

Ties to homelands

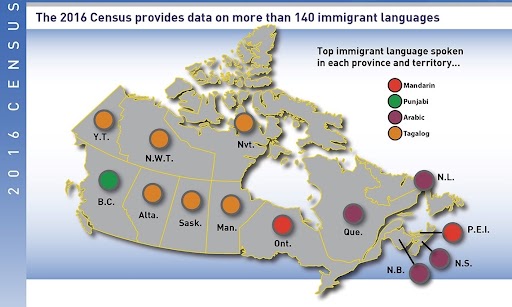

Immigrant and newcomer communities are not similar in terms of keeping and losing their mother tongues. Larger communities have closer ties and therefore have a better chance of maintaining their language.

The 2016 census also revealed that 22 immigrant mother tongues had populations of more than 100,000 people. The speaking rate is above 80 per cent for 16 of these languages, including all Asian languages. However, some European languages have much lower retention rates. For seven of these languages, the full retention rate is either below or barely above 50 per cent.

Sheyholislami says the chances of mother tongues surviving in Canada might increase for those languages in which major religions are practised or for languages from countries with embassies and cultural attachés in Canada that run language courses.

But “this is not the case with languages such as Tamazight, Kurdish, or Balochi,” he says. “A proactive and responsible language policy in Canada must consider these nuances into consideration. One size doesn’t fit all.”

Large immigrant communities have more frequent connections with their homeland and enjoy more support from the states of their origin compared to peoples like the Kurds who have a smaller population, and may not be at all free to even visit their motherland. Other immigrants may not enjoy cultural support from either their home state or from within the Canadian government itself.

Why does mother tongue matter?

Losing a mother tongue is not only losing a way to communicate with one’s immediate neighbourhood, it also means losing one’s own sense of identity and culture.

In an interview with NCM, Parvana Farhangpour, a Persian language instructor with a PhD in education, believes if immigrant children could speak their mother tongue, they would also develop a solid connection with their families, relatives, literature, and culture in their home countries.

Farhangpour has been teaching children their Persian mother tongue, instructing at the Persian children’s heritage language program in Toronto since the 1980s.

“The native language gives you more confidence and provides a sense of self-identity to know yourself better, where you come from, who you are, your heritage and history,” Farhangpour says.

We use a language or languages to get on with our lives, accomplish tasks — big or small — define ourselves, produce and store knowledge and understand ourselves and the world.

Solutions

Farhangpour recommends these methods to entice children and even adults to learn their native languages:

- Parents can encourage their children by reading stories about their home country in their mother tongue.

- In school, it helps to study languages.

- Schools should be asked to allow communities to establish weekend classes for mother tongues.

- Encourage children to listen to music and movies in their mother tongue.

- Communities can help each other in terms of experiences and methods of teaching.

Sheyholislami, on the other hand, believes that any responsible government has an obligation to not only cherish language diversity but actively promote and support children in schools, as well as promote other languages through the media, and in as many public domains as possible.

Finally, engaging in social media or using other online platforms for learning languages is another way to learn or maintain a language. NaTakallam is a social platform, powered by refugee talent and a host community, that provides services for learning languages.

These services include translation and interpretation services, online language teaching and tutoring, as well as cultural exchange sessions, both in academic and corporate settings.

___________________________________

Additional data reporting provided by Rachel Morgan.

Diary Marif is an Iraqi Kurdish journalist based in Vancouver, Canada. His writing has appeared in the Awene weekly, Livin, and on KNNC TV as a documentary researcher by the name Diary Khalid. Diary earned a master's degree in History from Pune University, in India, in 2013. He moved to Vancouver in 2017, where he has been focusing on nonfiction writing. He can be found on Twitter: @diary_khalid.

Speaking your mother tongue is not prohibited in any way. If someone values that historical tie they will practice it. The reality is that when someone moves to Canada, where English is the dominant language, they learn to speak English. That is quite sensible and does nothing to inhibit personal practices at home. When you immigrate to another country you should expect to adopt the language and cultural practices of that country. Canada accommodates all cultures, but everyone should clearly understand that Canada should not have to change its cultural practices to adjust to the immigrant. If an immigrant really doesn’t like the Canadian culture, they should consider returning to their “homeland”. There is a reason why they are in Canada, and the reason is that it is often so much better than where they came from.

True. You should accept poutine and beaver tails but if Canada calls itself multicultural making other food should be easy, eh?

Hardest part about the system is learning multiple languages.

Second generation (born in Canada, parents immigrants) will hear and talk mother tongue but emphasis on learning English. Harder in New Brunswick or Ottawa – mother tongue, English and French.

Your practicing in different places. Refugee and new arrival parents sometimes struggle with English/French; kids teach what they learn in school. Help parents, lose chance to practice mother tongue.

Language classes hard to find and high cost.