With the opening of a new session of Parliament next week, the campaign leading up to anticipated federal elections in Oct. 2015 is likely to shift gears. The so-called “immigrant vote” is very likely to be in play, and, according to academics who’ve studied this topic for many years, this electoral bloc is going to be even more crucial in 2015.

New Canadian Media interviewed Prof. Phil Triadafilopoulos of the University of Toronto, who last year published a chapter titled “Immigration, Citizenship and Canada’s New Conservative Party” (co-authored with Inder Marwah and Steve White), (in Conservatism in Canada, ed. David Rayside and James Farney. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2013).

We also reproduce relevant abstracts from the chapter to support his responses.

1. What were the main findings from this study?

I believe the key point is that the politics of immigration in Canada is the way it is because of the intersection of settlement patterns, our citizenship law, and our electoral system. There is a structurally induced predisposition for relatively pro-immigration policies and rhetoric, shared by parties across the ideological spectrum.

- We argue that the combination of immigrant settlement patterns, citizenship laws, and Canada’s single member plurality (SMP) electoral system create a context in which appeals to immigrant voters are required of any party with aspirations to national power.

- [T]he interplay of these structures ensures that immigrants are able to express their interests and have them acknowledged in a politically meaningful way.

- In sum, immigrants are concentrated in politically important urban regions.

- To alienate large numbers of immigrant voters in dozens of federal ridings would almost certainly mean surrendering those ridings to other parties.

- Data from recent Canadian Election Studies consistently show that visible minorities and immigrants tend to be more conservative than non-visible minority and non-immigrant Canadians on a number of contentious social issues.

2. You note that there was a dramatic change of stance on immigration as Reform/Canadian Alliance morphed into the Conservative Party. How do you explain this transformation?

Yes, this is one of the arguments we make in the chapter. The party had to compete in Ontario and to do so it had to get beyond its predecessors’ reputations as being anti-immigrant. The Conservatives could not simply declare this –[Minister] Jason Kenney had to go out and prove it in what amounted to political hand-to-hand combat (using handshakes as his weapon of choice).

- [O]ne of the central impediments to the Reform Party’s national ambitions was the widely held view of Reformers as anti-immigrant, anti-French, and generally intolerant.

3. Do you think Conservative policy changes serve Canada’s national interests in the long term?

Unfortunately, some do not. The expansion of the Temporary Foreign Worker (TFW) program will likely lead to trouble in the future (as people overstay and slip into undocumented status). Changes to citizenship policy were heavy-handed and based on political reasoning and weak ideologically-based reasoning. Changes to refugee policy has been unnecessarily punitive (and, again, taken for largely political reasons). There have been many other changes as well – judging their long-term consequences is difficult at the moment.

4. How were these changes different from ones that may have been made by the Liberals or the New Democratic Party, NDP?

The Liberals were similarly interested in narrowing access to asylum seekers and reforming the citizenship law – they failed to do so in part because the political incentives in the party were weaker. It’s likely that the NDP would have hewn to the status quo circa 2006.

5. Do you anticipate that immigration and citizenship will be major electoral issues in 2015?

No – immigration is typically not featured during elections, though all the parties will look to gain support among new Canadian voters.

6. Given your findings, what does your study suggest on the subject of immigration generally being a non-partisan issue in Canada?

It will likely remain the case. There’s no political pay-off for populist anti-immigrant rhetoric at the federal level.

- Canada is unique among major immigration countries in the degree to which immigration policy is de-politicized, and immigration itself is enthusiastically embraced by federal political parties. Quebec’s provincial politics since 2007 may be a partial exception to this pattern, but this has not had a discernable impact on Quebec voices in federal policy debates over immigration.

7. Do you have any further thoughts on the “immigrant vote” in the 2011 federal elections (you said it was inconclusive at the time of writing)?

We have not done the necessary analysis to move beyond what we have. We hope to do so soon. The key point is that all parties in Canada support a relatively liberal immigration policy, as reflected in annual admissions. There is also consensus on the utility of an official multiculturalism policy – our Conservative Party is rather different than similar parties in other countries.

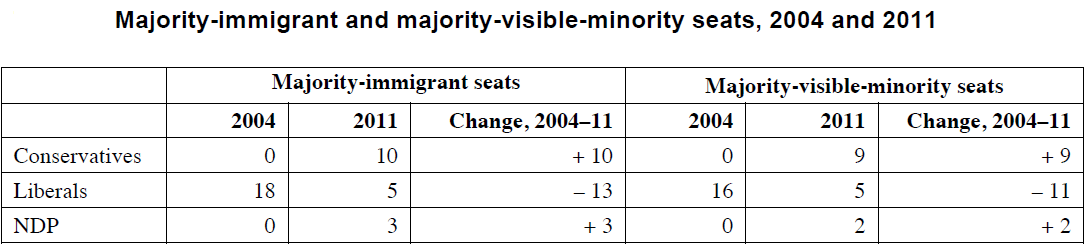

[In a separate study presented to the Canadian Political Science Association 2012 conference in Edmonton, Prof. Triadafilopoulos, Zack Taylor and Christopher Cochrane (all of UofT), concluded with this finding:- We focus especially on the Greater Toronto region because (a) 20 of the 23 seats gained in the 2011 election were located there, and (b) 41 per cent of foreign-born Canadians live there. Of the 20 new Conservative seats, eight were majority-immigrant and none had less than 30 per cent immigrant population. Similarly, three of the six seats picked up by the NDP were majority immigrant and none had less than 35 per cent immigrant population.

- Our findings suggest that the Conservative Party enjoyed marked gains among immigrant voters in the 2011 election, and that these gains appear to have come largely at the expense of the Liberal Party. Taken together, this evidence suggests that the party’s ethnic outreach strategy may have indeed borne fruit in 2011. The NDP(New Democratic Party) also appears to have benefited from the support of a different segment of support that overlaps with the immigrant electorate: visible minorities.]

8. Do you think the “immigrant vote” will play a more critical role in 2015?

I do. Canada is changing quickly and the trends we identified are still playing themselves out.