Ciro Alquichire covered the Colombian military war for almost a decade, but after living in Canada for 18 years, he laments: “I have not been able to practise here the journalism that I did in Colombia.”

In the 1990s, he covered the Colombian war in “red zones” like Barrancabermeja, disputed territory among the military, the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) and drug cartels. His investigative report about the children of the war received an award from the Inter-American Press Association.

But the prestige didn’t stop the “death threats,” he told New Canadian Media.

“At first, I ignored it because that happened to the reporters who covered the war. We thought it wasn’t true until journalists began to die.”

In 2018 and 2019, Latin America and the Caribbean registered the highest number of journalists subjected to politically-motivated assassinations, according to a report from the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. In general, it states, more journalists are killed for writing about corruption, trafficking and human rights violations than armed conflict.

The Committee to Protect Journalists documented 53 Colombian journalists killed in Colombia and 56 in El Salvador from 1992 to 2021.

Alquichire sought refuge in Canada in 2002. Living in a country as safe as Canada, he says, he discovered what he called “another reality of journalism.”

“I started working for Hispanic newspapers in Toronto, but I had to cover concerts, take photos, and write entertainment news. Very different from what I did back home,” said Alquichire who, since 2012, has been editor-in-chief of La Portada newspaper.

Dearth of Latin American media

For him, social media has driven the dearth of Latin American-driven media, meaning journalists have had to find other alternatives to earn an income. In his case, he also does photography and designs advertisements.

Amanda Ramirez (an assumed name), who requested anonymity because her asylum request is ongoing, said that she had to flee El Salvador, where she had been receiving death threats and ran the danger of being kidnapped after writing about the gangs Maras Salvatrucha, commonly known as MS-13, and Pandilla 18.

“It is difficult to work as a journalist in Canada. The Latino community is small, and Hispanic media do not have the resources to hire staff reporters,” said Ramirez, who pointed out that most Latin American outlets “are not run by journalists.”

After seven years in Canada, she feels “stuck in limbo” because her refugee process has taken a long time and she cannot pursue a university education.

She also juggles being a journalist and a full-time mother of two. She has limited access to daycare because it’s “expensive, and to get a subsidy we need to prove a full-time job, which is difficult during this pandemic,” she says.

Outsourcing and social media

For Juan Gavasa, a writer and journalist from Spain, speaking Spanish helped him land a job as a journalist two years after arriving in Canada.

By 2013, he was full-time editor-in-chief for PanamericanWorld, which collaborates with local correspondents in Latin America. Two years later, however, he was reduced to a part-time post. The publisher ultimately replaced him with a journalist outside Canada.

“Some publishers prefer to pay journalists from other countries than to pay us here in Canadian dollars,” says Gavasa.

Like Alquichire, Gavasa also points to social media as a problem for journalists.

“Journalism is experiencing a global crisis. My colleagues in Spain have the same problem,” said Gavasa, who does not hide his disappointment of the “new journalistic narrative” that is coming with social media.

“Now, there is less journalism and the most important (pieces) are the 280-character messages, the number of followers and views on social media.”

Gavasa, who co-founded XQuadra Media and Lattin Magazine in 2016, says he is “skeptical” about the possibility that mainstream media outlets will begin hiring more immigrant journalists, even if the industry is undergoing a reckoning of sorts.

For now, he finds solace continuing working on his own media.

“We have had good clients, but it has not been constant,” he adds, pointing to the proliferation of newspapers and media outlets in the Hispanic community. “There is almost one media (organization) per journalist.”

If they don’t hire you, create your own

Television journalist Martha Pinzon spent over 20 years trying to land a job in the Canadian media industry. It has been a disappointing experience, she shares.

“I knocked on the door of CBC, CTV, CP24. I texted them, emailed them, but they never responded.”

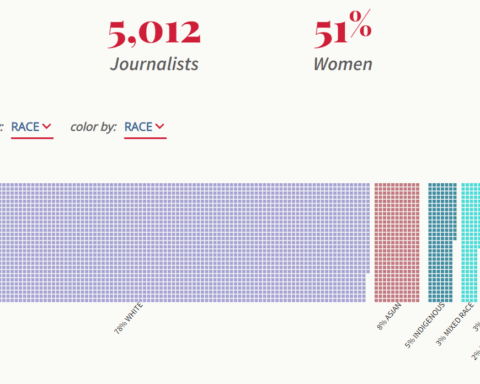

A recent study by the Canadian Association of Journalists on diversity in Canadian newsrooms found that “almost half of all Canadian newsrooms exclusively employ white journalists,” while Latin American journalists represent just 1 per cent of their staff.

Pinzon worked at TLN for seven years. She also worked eight years at the community radio station Voces Latinas, where she was a staff broadcaster but “the salary was very low.”

Under the motto “networks with content,” in 2019 she started her own media channel, @MarthaPinzonMedia.

“I have been able to count on the support of some sponsors who consider my work to be valuable, but I have not had any extra support, as other media do,” said Pinzon, who is also Colombian and a mother of two.

Linguistic, cultural barriers

All four Ontario-based journalists agree the main barrier has been the English language.

“If you can write in English, you can take off,” says Alquichire.

“Most editors would choose a Canadian journalist over an immigrant journalist,” adds Gavasa.

For Pinzon, the mainstream media fails to grasp that linguistic diversity is part of the Canadian fabric. She says that this limitation does not allow opportunities for immigrant journalists that can contribute to the growth of the profession.

“I have experience in politics, courts, state processes, and I can contribute a lot in investigative reporting…we can work in newsrooms where we can contribute our experiences,” Pinzon says.

“But mainstream media easily dismisses us.”

To overcome these barriers, the journalists highlight the importance of paid internships and scholarships to allow immigrant journalists to gain experience in the media industry. They also point to the need for more permanent staffing positions for ethnic reporters.

This article is part of NCM’s study on the socioeconomic conditions of first-generation immigrant and refugee journalists currently in progress. Please fill out our immigrant/refugee survey here: English survey French survey.

Editor’s note: Professional and ethical journalism guidelines state that all claims must be corroborated and backed up by evidence and credible sources who are clearly identified. However, this isn’t always possible to do when security and safety issues, for instance, are at play. Please, take a look at this guide published by NCM to learn more about the ethics behind naming sources and using anonymous ones.

Isabel Inclan has worked as a journalist for more than 20 years, in both Mexico and Canada. She began working as a foreign correspondent in Canada in 1999 for Mexican media. She has been a New Canadian Media contributor since 2018. Her main areas of interest are politics, migration, women, community, and cultural issues. In 2015, Isabel was honoured as one of the “10 most influential Hispanic Canadians.” She is a graduate of Masters in Communication and Culture at TMU-York University. She is a member of CAJ and a member of the BEMC´s Advisory Committee.