Canada relies on the thousands of temporary foreign workers who come to work in the agricultural sector each year, primarily in Ontario. Yet the workers are often left overly-dependent on their employers, making them especially vulnerable to exploitation.

This is why a team of researchers at the University of Guelph are looking into how gender-based violence impacts temporary foreign workers in the agricultural stream.

The team, led by professor Silvia Sarapura, has been looking into knowledge gaps in existing research and documentation since January, and whether there is a need for more research or policy changes.

While they’re only in the analyzing stage, the gaps are so significant that they already know there needs to be more targeted research around gender diverse experiences, and better policies to protect workers.

For example, most research talks about a power imbalance between the employer and employee, treating TFW’s as if they all have the same experience. But the agricultural streams are heavily racialized and gendered

“Only three per cent of women make up the seasonal agricultural workers program,” grad student Nicole Cupolo said. This is in part because employers can select who they’d like to work for them, and many choose not to take on women.

This severe under-representation within the program makes them vulnerable to gender-based violence, including harassment or wanting a sexual relationship with a worker and giving them more undesirable work if that doesn’t happen.

While it’s generally known TFW’s experience gender-based violence, research hasn’t really gone beyond stating that fact, grad student Regan Zink said. This also means it’s impossible to tell how common an occurrence it is.

Access to essential services like healthcare is also a problem. Since farms aren’t within walking distance to these services and there isn’t usually any other transportation, employers are often responsible for driving them there.

“Often, workers won’t want to say they’re not feeling well, not only because there could be implications for pay, but also because they’d have to ask their employer to drive them somewhere,” Zink said.

Some won’t even drive them unless it’s an on-site injury, meaning reproductive concerns aren’t usually a huge priority for employers, she said.

“In some instances, women have gotten pregnant. And if that information becomes known to the employer, they are sent home, and they lose out on the opportunity of finishing work for the rest of the season,” Cupola said. “So a lot of women, if they do become pregnant, try to hide that information for as long as they can.”

In some cases, employers have rules about workers not having sexual relationships. So if a worker has an STI, for example, but their employer has to drive them, they might forgo going to the doctor altogether.

In general, TFW’s are unlikely to come forward with reports of harassment or complaints of exploitative conditions for fear of losing employment and being sent back to their home country.

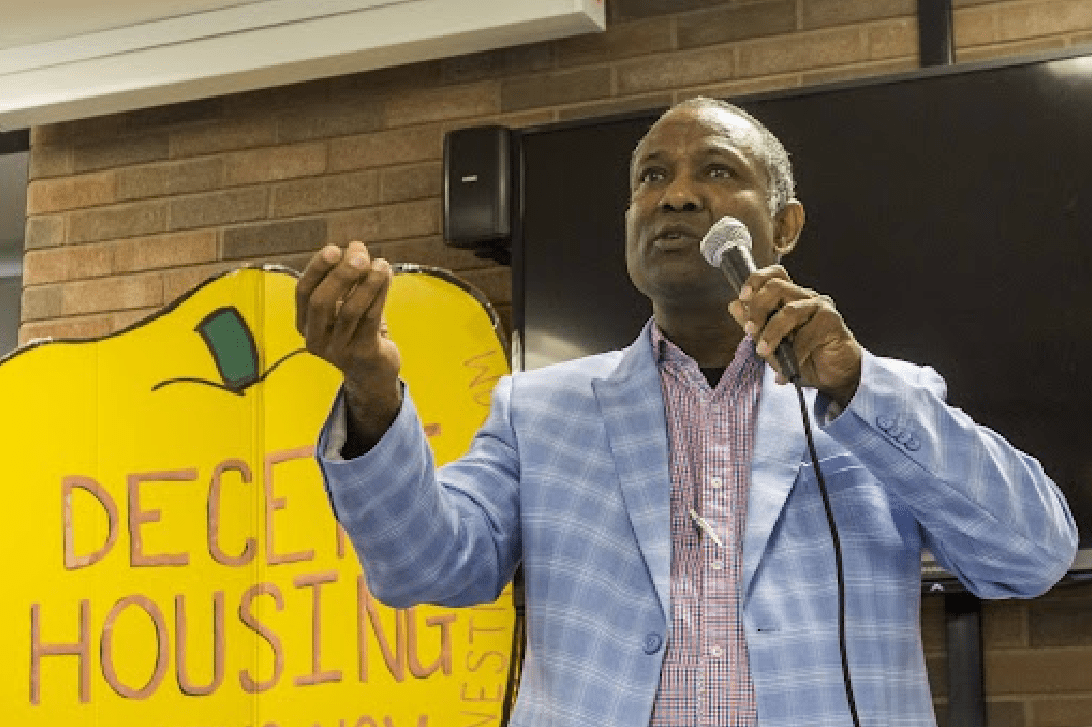

University of Guelph activist in residence and former temporary foreign worker Gabriel Allahdua can attest to this.

Allahdua came to Canada from Saint Lucia in 2012 through the agricultural program, working at a farm in Leamington, Ont.

He said workers are unlikely to speak up because they’re scared of returning to the conditions in their home country that they fled from in the first place, and the conditions on the farms make it difficult to safely share their concerns.

While his farm only employed men, he’s made connections with women at other facilities.

“They had a curfew … difficulty accessing healthcare,” he said. In one facility, he said there were cameras to monitor them.

“Somebody who is in fear, who will they trust? So that’s another reason why a lot of people would rather go through the motions in the program, and at the end of the week, they know they have money for their families. They’d rather keep quiet than to speak up and stand the risk of being deported.”

There is a complaint tip line, but he said whatever an employee says on it can be traced back to them. And even if they can speak to their liaison, he said often the liaison takes the side of the employer.

Zink said their research will help inform policy-makers around what needs to be done to address gender-based violence in the temporary foreign worker program, how to offer more protection for those workers, and to eliminate some of that vulnerability.

But Allahdua already has some ideas, including granting migrant status to address the power imbalance, automatically giving temporary workers more rights.

If this happened, he said they wouldn’t be afraid of speaking up, as they wouldn’t be so dependent on their employer.

“That’s the power that they need,” he said.

_____________________________________________________

This Village Media story was written as part of New Canadian Media’s microcredential on inclusive journalism. It was originally published on Guelphtoday.com

Taylor Pace

Taylor is a journalist based in Guelph. She started with Village Media two years ago, and is currently a general assignment reporter at GuelphToday.