The recent sentencing in Iran of a volunteer teacher for simply teaching the Kurdish language to children is shedding light on the plight of the Kurdish people’s sense of identity and culture both in that country and within the Canadian diaspora.

On Jan. 8, Zara Mohammadi turned herself in to Iranian authorities after having been sentenced to five years in prison by the Islamic Republic Judiciary of Iran on charges of “establishing a committee against the stability and security of the Iranian system,” Rudaw reported.

Mohammadi is a 29-year-old Kurdish social activist and teacher from the Kurdish city of Sine, or Sanandaj, in Iran, who taught the Kurdish language at Nojin Socio-Cultural Association, an organization tasked with teaching the Kurdish language and literature and where she served as a board member.

According to Iran’s Constitution, while Persian is the only official language, “the use of regional and tribal languages in the press and mass media, as well as for teaching of their literature in schools, is allowed.”

That’s why Amnesty International first reported that she had been “arbitrarily detained since her arrest” in May 2019 and then charged in November of that same year.

The situation has not only disappointed Kurdish Canadians, but many say they feel hopeless they will ever have the chance to officially learn their mother tongue.

Masoud Hashmi, a human rights activist and a Vancouver-based journalist, came to Canada several years ago with his family from the Iranian Kurdish city of Kermanshan. He says Mohammadi’s sentence further cements the fact that 10 million Iranian Kurds are being kept from studying in their mother tongue in their own homeland, while those in the diaspora have no way to learn it.

“The Iranian government assimilates the Kurdish people under the umbrella of the Persian culture and language, which is akin to Kurdish language-cleansing,” says Hashmi.

The power of language

At the end of World War I, the Sykes-Picot Agreement demarcated the Middle East along Anglo-Franco imperial spheres of control, leaving 25-30 million Kurds scattered across Turkey, Iran, Iraq and Syria.

Since then, the Kurds have had no right to study in their language in Turkey and Iran. In Iraq, Kurds began studying their language after gaining semi-autonomy in 1992. Syrian Kurds started studying in Kurdish after 2011.

After former Iranian supreme religious leader, Ayatollah Khomeini, took over Iran in 1979, as well as in subsequent regimes, Kurds, Balloches, Azaris, and Arabs were all brought under both the “All Muslims are Brothers” and “Iranian People” slogans.

According to Azada Rahmanie, a Kurdish political-philosophy researcher at Paris 8 University of Vincennes Saint Denis, in Paris, France, unlike other regimes who used brutal force to invade, subjugate and ethnically cleanse Kurdistan, Iran has been using soft power to manipulate and control the Kurds by invoking the “brotherhood” for more than 40 years.

That’s why she considers Mohammadi’s case to be emblematic of a continuous attempt to suppress the Kurdish language, something she says is directly connected to one’s sense of identity.

“The Iranian authorities allow you to enrich your culture, but they do not allow you to learn your language because they know the mother tongue helps you to find your identity, yourself and be confident,” she says.

Rahmanie was also born in Sina, like Mohammadi. And like many, she is frustrated with what she considers an unfair trial. She believes Iranian authorities persecuted Mohammadi because “authorities do not like the Kurdish language” and because she “did not work for (Iran’s) interests (but) against them.”

No official recognition

Many Kurds like Hashmi and Rahmanie are worried about the new generation of Kurds within diasporas in Western countries, as there are no institutes to teach the Kurdish language, nor can they go back home to learn it.

Rahmanie says in Iran, Kurds are seen as second-class citizens and usually relegated to jobs as bodyguards and porters. Thus, when they immigrate to Canada (or other Western countries), they do so with an eroded sense of self and of identity.

Hashmi adds that while Canada is welcoming to visible minorities and racialized newcomers, the Kurdish people are “ignored” as they are only recognized to be Iranians and nothing is done to revive any official use of their language.

Canada’s two official languages are English and French, according to section 23 of the Charter of Rights and Freedoms. And while minorities are encouraged to teach and promote their language, there is no official support for Kurds to learn theirs.

Homa says “Canada needs to create incentives in the school systems for students to learn literacy in their mother tongue…(as) growing up multilingual will benefit the young generation in numerous ways.”

NCM contacted Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada (IRCC) asking of the possibilities of establishing schools or learning institutions for Kurds to learn their language but did not hear back.

Short-lived dream

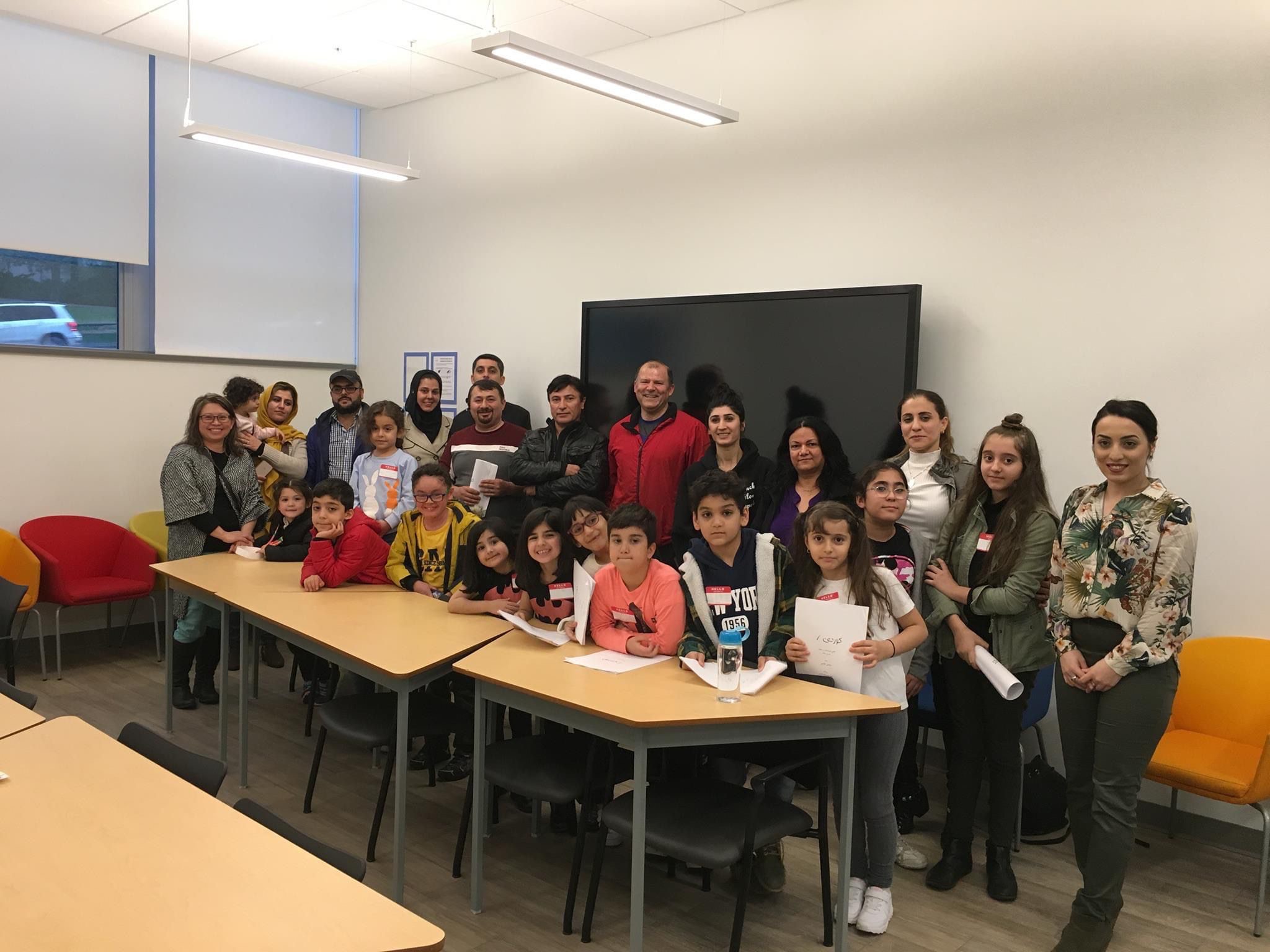

In 2019, the Kurdish community Mali Kurdi established a one-class school to learn the Kurdish language called Xwendngay Kurdi at the headquarters of MOSAIC, one of the largest multilingual settlement non-profit organizations in Canada based out of Vancouver, British Columbia.

Two Kurdish volunteer teachers, Kamaran Mohamad and Shireen Tofeeq, taught the students, but due to COVID-19 and lack of adequate teaching facilities, the school had to be closed.

But even the short-lived six months that the school was opened felt like a dream-come-true to many Kurds. Despite traveling from faraway suburbs such as North Vancouver, Coquitlam, and Port Coquitlam, Mohamad says students “enjoyed their short time in class, and their families were so excited about the school.”

Mohamad says he believes the reason Kurds in Iran and in the diaspora fight for their language is because “it’s their identity and their culture.”

“That is why the children and their parents were thrilled about the school,” he says. “If the Canadian authorities helped us, we would maintain the school and could teach Kurdish to many children.”

A ‘loss for human civilization’

In 2017, Kurds played a key supporting role to the USA and its allies in the fight against the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS).

In an interview with NCM, Ava Homa, the author of Daughters of Smoke and fire, explained Kurds have thrived and have relied on arts and literature to survive endless attacks and acts of genocide. Both at home and in the diaspora, Kurdish academics, filmmakers, musicians, artists, writers, and fighters have contributed much to the world in spite of their struggles.

Homa believes the Kurdish people’s mantra of “Resistance is Life” is symbolic of their resilience to a world ravaged by division and injustice.

“Their language, however, is in danger of extinction,” she says. “And the loss of any language is a major loss for human civilization.”

Diary Marif is a Vancouver-based Kurdish writer and award-winning journalist born in Iraq. He holds a master’s degree in history from Pune University in India (2013). His journalism has appeared in national and international outlets, including Rabble, Canadian Dimension, CBC Arts, Culturico, The Amargi, and The Canadian Encyclopedia. Since 2018, Marif has centred his creative work on memoir and personal narrative, exploring his experiences as a child of war. He has written chapter books for multiple projects and has appeared as a storyteller in public spaces. He received an Honourable Mention for the 2022 Susan Crean Award for Nonfiction, is a 2025 recipient of the Yosef Wosk Vancouver Manuscript Intensive Fellowship, and was awarded PEN Canada’s 2025 Marie-Ange Garrigue Prize.

Well written and to the point. Thanks Dyari for bringing up a vital issue that we all need to address.

For a German Philosopher, Marrin Hadigger, “Language is the house of Being.” To put it simply, the very existence of Kurds depends on preserving their language since they don’t have a sovereign state. Since the Kurdish language has been under systematic eradication by Turkey and Iran states, it is vital for the Kurdish diaspora worldwide to pressure countries they reside in, including Canada, to provide facilities for Kurdish kids to learn their language.

Thank you, Diayri, for starting such a vital disscution.

Great job, Thanks Dyari you have emphasized certain points that millions of Kurds have faced for many years. Many languages in the world have dissolved under certain regimes through genocide, but Kurds have always stood for their rights and have paid a heavy price.

[…] گزارش هفته و به نقل از newcanadianmedia، زهرا محمدی از سوی قوه قضائیه جمهوری اسلامی ایران به […]