In a country where over one in five people are immigrants and far more are children and relatives of immigrants, questions of who gets into Canada and how decisions are made on immigration matters are of central concern. For instance, does the immigration system profile people from particular countries or specific ethnic or racial backgrounds? How is family sponsorship evaluated? And why do some people get visas to visit while others don’t?

Questions like these are tackled head-on by McMaster sociologist Vic Satzewich in his prize winning book Points of Entry: How Canada’s Immigration Officers Decide Who Gets In. He offers a comprehensive overview of Canada’s immigration system by looking at the overall social and political context driving immigration, the organizational structure of the Immigration department, and most interestingly, how immigration officers on the ground make decisions on individual applications and prospective immigrants. [We have excerpted a section of the Introduction to give readers a flavour of the kind of dilemmas visa officers face.]

Biases in the system

The professor visited 11 visa office abroad between 2010 and 2012 across all regions and also met with officials in Ottawa several times. In his visits he tagged along with visa officers to see how they do their jobs, reviewing field operating notes and discussing with them about how they make their decisions.

He was particularly interested in examining the discretion that immigration officers have in their decisions, and their role as, what he calls, street-level bureaucrats. Their discretion and ability to make on the ground decisions have led some to question whether there are biases and hidden agendas in Canada’s immigration system.

Satzewich found no direct evidence of discrimination in approval and refusal rates across visa offices around the world, nor did he observe it through the practices of immigration officers. In fact, he found little variation in rates across regions and source countries, with officers very aware of the need for consistent application of policies. He drilled down into specific visa categories by looking at decisions made around spousal and partner sponsorship, decisions on those applying under the skilled worker program, as well as those seeking visitor visas.

Satzewich found no direct evidence of discrimination in approval and refusal rates across visa offices around the world, nor did he observe it through the practices of immigration officers.

Continual change

His analysis of the family pathway offers important insights on the Canadian government’s concern with marriage fraud. His analysis is vivid and colouful, with descriptions of what goes into case processing and an explanation of how immigration officers identify anomalies they want to investigate and then ultimately the interviews they conduct with prospective immigrants and their sponsors.

His analysis of skilled workers offers a similar level of insight.

During his field research, Canada’s immigration system was in a period of rapid and constant change. Former immigration minister Jason Kenney tweaked how the system worked on a regular basis, ultimately leading to fundamental changes to the immigration system. Satzewich tracked those changes and how it affected the system and on the ground decisions by immigration officers.

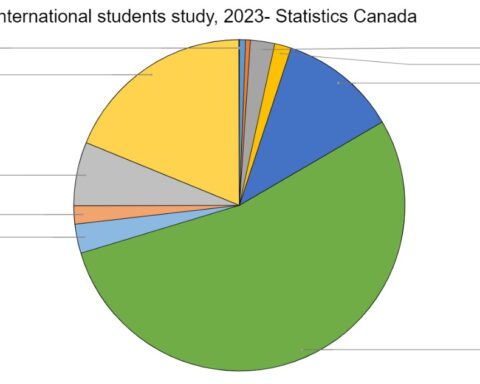

One significant change documented is the increased importance of visitor visas over permanent residency with the introduction of a super visa for parents and grandparents, the rise of temporary foreign worker applications, and a move towards attracting more international students.

Another important change was the previous government’s move to rationalize the processing of immigrants and speed up the processing time.

Increased pressure

Rather than finding overt bias and discrimination in the immigration system, what Satzewich found was an increased pressure on immigration officers stemming from a move towards immigration processing targets, faster deadlines, increased use of impersonal evaluation criteria, the auditing of their decisions and a move away from interviews and discretionary autonomy.

… Satzewich found was an increased pressure on immigration officers stemming from a move towards immigration processing targets, faster deadlines, increased use of impersonal evaluation criteria, the auditing of their decisions and a move away from interviews and discretionary autonomy.

Despite all the changes, Satzewich did not find a nostalgic longing for “old times” among the immigration officers he spoke with. In part, this is because of generational turnover, with fewer and fewer officers having worked in the immigration system when their on-the-ground decisions carried more weight in the evaluation of files.

His research ultimately shows that Canadian immigration officers are highly dedicated to their jobs and recognize the weight of the decisions they make on a daily basis.

CLICK FOR EXCERPT:

Points of Entry: How Canada’s Immigration Officers Decide Who Gets In

Maria enters the interview booth with a broad, confident smile. Brenda, the visa officer responsible for reviewing her application, smiles back and asks her to close the sliding door behind her. There is no chair on Maria’s side of the small, six- by eight-foot interview booth, so she takes a few seconds to put her bag on the floor and try to get comfortable for the interview.

She ends up leaning against the small ledge in front of the bulletproof glass window that separates visa applicants from visa officers. A few years ago, Canadian embassies installed the special glass in their interview booths because of safety and security concerns. People sometimes get angry when their visa application is refused, and in this day and age, you can never be too careful.

Brenda points to the telephone on the wall and gestures to Maria that she should pick it up. She welcomes Maria and introduces herself as “the visa officer responsible for your case.” She asks Maria in English if she can understand what she is saying. Maria nods in agreement, but Brenda asks her to please say “yes” or “no.” Maria says “yes.” Brenda needs a verbal response because she has to document her decision-making process by keeping notes of the questions asked, Maria’s replies, and her own assessment of the answers.

Brenda then asks if she is comfortable conducting the interview in English, and since Maria lived in the United States for several years, she says “yes” but asks that Brenda “speak slowly.”

Brenda already knows a lot about Maria and her circumstances from the spousal application for immigration that she and her Canadian sponsor submitted eight months ago. Maria’s husband wants her to join him in Saskatoon, and as part of the application, couples are asked to tell the story of their relationship. Brenda reviewed the application about a month ago, but something about the couple’s story did not add up. Her program assistant contacted Maria to schedule the interview so that Brenda’s concerns could be addressed.

Visa officers do not interview every applicant for admission to Canada. In fact, headquarters in Ottawa likes them to keep the number of interviews down and encourages them to make their decisions solely on the basis of the information in the application. Interviews take a lot of time, and time in a visa office is in short supply. Officers are trained to make their decisions to approve or refuse visa applications relatively quickly.

Brenda has two or three dozen files stacked on the corner of her desk and on top of two filing cabinets in her office. Her program assistant is working on a couple dozen other files at various stages of processing. Globally, there are thousands of applications in what Citizenship and Immigration euphemistically calls its “inventory,” which is its code word for “backlog.” The more time Brenda spends on one file, the longer other applicants must wait for a decision.

Officers must also meet their yearly visa issuance targets. It is early December, and Brenda’s office has not yet met its target for family class spousal visas. If Brenda fails to meet it, this will reflect badly on her and on her boss, the immigration program manager. Headquarters in Ottawa will also be unhappy because it will have to find another visa office to pick up the slack. All the other offices are also working hard to meet their own targets, so a last-minute request to increase a target because another office has not met its own quota means that something has gone awry.

If no other office manages to fill the gap, the overall target for family class admissions will not be met, and the immigration minister will want to know why. The minister announced the targets the year before in Parliament and will be held accountable by the Opposition if the number of visas falls far below, or far above, them. Since politics are politics, Opposition colleagues can be rather unforgiving in their assessment of a cabinet minister’s performance and will relish any opportunity to cast the minister as incompetent or as failing to control his or her department.

In a family class spousal sponsorship case, such as that of Maria, Brenda must be “satisfied” that the relationship between Maria and her husband in Canada is “genuine” and that its primary purpose is not for Maria to gain permanent resident status in Canada. Upon reviewing the file a month earlier, Brenda suspected that this might be a marriage of convenience. She uses the interview to figure out whether the relationship is real and whether its primary purpose is immigration.

After asking a few simple, factual questions – Maria’s full name, date of birth, and other matters that already appear on the application – Brenda starts to focus more closely: “It says on your application that you lived in the United States for fifteen years and that you returned to Guatemala three years ago. Why did you return to Guatemala after living for so many years in the United States?” Maria explains that she missed her family and returned to Guatemala to be closer to them. This sounds odd to Brenda, who thinks to herself, “Why would someone voluntarily leave the United States to go back and live in Guatemala?” She suspects that Maria is concealing something, so she pointedly asks, “Were you deported from the United States?”

After pausing for a moment to reflect on her answer, Maria admits that she was slated for deportation but chose to leave before the American authorities put her on the plane. She does not explain why she was going to be deported, but Brenda puts two and two together and surmises that Maria probably overstayed her original visa and then somehow caught the attention of US immigration authorities. For Brenda, Maria’s original evasive answer to the question of why she left the United States confirms her concerns and prompts her to dig deeper.

She moves on. “How did you meet your husband?” Maria explains that they first met at the birthday party of a mutual friend when they were both living in Los Angeles. They dated a few times, but nothing really came of the dates. A few years later, they met again at another birthday party of a mutual friend, this time after she had returned to Guatemala.

Brenda also knows a fair amount about Maria’s husband. She has access to the Field Operations Support System database, which contains information about the application history of everyone who has applied for admission to Canada in the past several years. Before the interview, Brenda pulled up the file for Maria’s husband, which told her that he, too, is from Guatemala and that seven years ago he submitted a successful refugee claim in Canada.

He had lived in the United States for several years but then crossed the border into Canada at Surrey, British Columbia. She suspects that he, too, was scheduled for removal from the United States and that rather than return to Guatemala, he decided to take a chance with the Canadian refugee determination system. When he crossed at Surrey, he must have uttered words to the effect that “I am a refugee.” As soon as Canada Border Services Agency staff heard the word “refugee,” a complex refugee determination process came into play.

Ultimately, Maria’s husband convinced the Refugee Protection Division of the Immigration and Refugee Board that he was genuinely in fear of his life in Guatemala, so he was granted permanent residence status in Canada.

After this, he returned to Guatemala to visit some old friends, where “by chance,” he met Maria again. Since he planned to be in Guatemala for a month, they started dating, and this time they fell in love. Within two weeks, they were married at a small civil ceremony. A few close friends attended. Though his mother and two brothers lived in Guatemala, they were not at the wedding. Maria explains that they lived “far away” and could not travel to Guatemala City for the wedding. She adds that her mother and sister stayed away because they thought that her husband was not “good enough” for her.

As Maria explains the circumstances of how she met and married her husband, Brenda looks through a pile of thirty or forty photographs that the couple included in the application to support the story of their relationship. The photos show the marriage ceremony and the small reception that followed it. One shot shows about twelve guests seated at a large restaurant table, all happily toasting the bride and groom.

The other pictures are of the wedding night and the honeymoon. The wedding night photos show the couple in the bedroom. She is wearing lingerie; he is in a bathrobe with his chest exposed. They are lying on a bed, smiling directly into the camera and toasting with champagne. Brenda looks at these pictures and cracks a barely visible smile. She thinks to herself, “Why on earth would they have a photographer in their bedroom on their wedding night?” The honeymoon photos show the couple on a beach in Panama. Maria explains that they chose Panama because they got a good deal on a package offered by a local resort. Shortly after their honeymoon, Maria’s husband returned to Canada and began the process of sponsoring her for permanent resident status.

Brenda then turns to the issue of children. “It says on your application that you have a child in the United States.” “Yes, she is grown and goes to college.” “Were you ever married before?” “No, this is my first marriage.” Finally, Brenda moves on to questions about Maria’s relationship with her husband. “It says on your application that you talk to your husband every day for about twenty minutes.” Also included in the file are a stack of phone cards that Maria says she uses to call her husband in Saskatoon.

The cards provide no information about the numbers that were dialed or the length of the calls. Since, in themselves, they are not evidence of much, Brenda asks, “So what do you talk about with your husband when you call?” Maria says that they talk about how much they love and miss each other, and how they can’t wait to be together again. Brenda smiles, but then asks, “Okay, but you can’t talk about love all of the time. What else do you talk about?” “We talk about our lives and our future life together, things like that.” At this point in the interview, Brenda starts to drill down, to look for specifics. In her view, real couples talk about more than just love: genuine partners have some knowledge of each other’s past and everyday lives and circumstances.

“Where does your husband work?” “A trucking company; I think its name is On Time Trucking, or something like that.”

“What is the name of your husband’s boss?” “I don’t know.”

“What are the names of some of the people he works with?” “He does not really have any friends at work.”

“What are the names of his non-work friends?” “He sometimes talks about a guy named Sam, who lives in the same apartment building.”

“What kind of apartment does he live in, and how many bedrooms does it have?” “I don’t know.”

“What is his favourite meal?” “Hamburgers.”

“What does he like to cook for himself?” “Hamburgers.”

“What was the last movie he saw?” “Friday the Thirteenth.” “So, he likes scary movies?” “Uh huh.”

This back-and-forth about Maria’s knowledge of her husband and his life in Canada lasts about ten minutes, and then Brenda asks, “Are you looking forward to moving to Saskatoon?” “Yes, very much.” “What is Saskatoon like?” “I don’t really know, but it seems it is a lot like California.” Brenda, visibly surprised by this answer, says, “Really? What makes Saskatoon like California?” Maria pauses for a moment and replies, “There is shopping there, it is clean, things like that.” “Have you ever seen any pictures of Saskatoon in the winter?” “No.”

The interview lasts for about an hour, and after the last question Brenda takes a few minutes to review the overall application and digest Maria’s answers. She then tells Maria that she is not satisfied that her relationship with her husband is genuine, and that she believes that the primary reason for her marriage is to gain permanent resident status in Canada. She details the “concerns” that have led to her assessment. Maria listens with apparent surprise that her story is not believed and spends the next few minutes trying to address each of Brenda’s concerns by repeating what she has already said. After listening intently, Brenda says, “Thank you, I am ready to make my decision.”

In the end, what decision do you think Brenda made? Did she grant Maria her family class spousal visa, or did she refuse the application? Was Maria in a real relationship, or was it a fake? Did she get married primarily because she wanted to become a permanent resident in Canada or because she loved her husband and wanted to start a new life with him?

Canadian visa officers must answer these kinds of questions every day. They make decisions about who should, and should not, be issued a visa to enter Canada, both as permanent and temporary residents.

Excerpted with permission from Points of Entry: How Canada’s Immigration Officers Decide Who Gets In, by Vic Satzewich, 2015, UBC Press, Vancouver and Toronto, Canada.

Howard Ramos is a Professor of Sociology at Dalhousie University. His research focuses on issues of social justice including the non-economic elements of immigration and examination of family and non-economic streams of immigration to Canada.

Howard Ramos is a political sociologist at Dalhousie University, Halifax, who investigates issues of social justice and equity. He is currently working on projects looking at Atlantic Canadian, secondary cities, integration of immigrants and refugees, hockey and multiculturalism, and the social implication of AI and new technology.