Kalpesh Patel came to Canada from India as a permanent resident in April 2022; he thought he had everything that would help him contribute to the labour shortage in the country. But Patel has still not found work that matches his skills.

Patel, a 27-year-old Halifax resident, had worked as a field executive in social relations and networking at a hospital in India for five years before coming to Canada under National Occupation Classification 4212 – Social and community service workers.

In an interview in Gujarati, he said,”I have applied to 400-500 jobs since I have come here.”

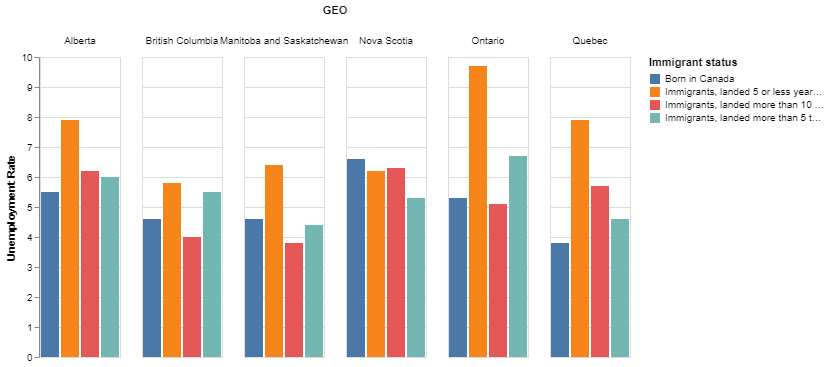

Even at a time of record high employment, immigrants who have been in Canada for less than five years had the worst job numbers in 2022 when compared to other immigrant cohorts and people born in Canada. In different provinces, unemployment numbers differed, with Ontario having the highest disparity.

Data from Statistic Canada’s 2023 labour force survey said that unemployment rate of recent immigrants was 8.2 per cent, immigrants landed more than five to 10 years earlier was 5.8 per cent, immigrants landed more than 10 years earlier was 5.1 per cent, and that of people born in Canada was 5 per cent in 2022. The numbers have always been the worst for recent immigrants.

Patel completed his Master’s in Social Work and came as a part of the Federal Skilled Worker program. Skilled workers are chosen as permanent residents based on their education, work experience in one of the 370 eligible occupations, knowledge of English and/or French, and other factors. The government of Canada says on their program page, “these things often help them succeed in Canada.”

Patel works part-time at Walmart.

“I had no choice but to change my field and work as a clerk instead of an executive,” he said.

A disconnect

Stein Monteiro, a senior research assistant at Toronto Metropolitan University focuses on issues of assimilation and integration among new immigrant groups. Monteiro sees this gap as a disconnect.

“The government would bring in people, who according to the point system are considered very high-skilled but when they actually do come to Canada, they don’t find jobs in their sectors… So, that disconnect between government officials and employers in permanent residency pathways is quite wide.”

Monteiro says a reason behind the gap could be a result of the “deskilling process,” where immigrants’ skills are being undervalued.

“One of the main reasons why the initial years are so difficult is because educational qualifications from their home country are not being recognized.”

Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada, in an emailed response said, provinces and territories are responsible for most regulated professions and trades, and in most cases they further delegate that authority in legislation to regulatory bodies.

“The process is complex and can be lengthy depending on what the individual needs to complete to become certified and how long that may take him or her,” the response said.

IRCC said it is working with Employment and Social Development Canada as the federal lead on the Foreign Credential Recognition Program, as well as with provinces and territories, to make collective advancements on foreign credential recognition in Canada.

IRCC, in its response, noted the unemployment rate of recent immigrants in 2022 was the lowest it has been in several years, according to Statistics Canada.

Available labour force survey data shows that the gap between unemployment numbers for people born in Canada and recent immigrants has declined over the years, but a Statistics Canada study from 2001 to 2019 found this to hold true only for new immigrant men. In the last twenty years, the gap shrunk by 5.6 percentage points for recent immigrant men, but grew by 3.3 percentage points for women in terms of employment numbers when compared to their Canadian-born counterparts.

Monteiro says even after years, there is a concern that lingers.

“Over time, most cohorts, regardless where they come from, tend to converge with the native-born Canadians. But your graph shows, even after more than 10 years many groups don’t converge with native-born levels so that’s a bigger problem.”

Patel believes that he is not able to match the communication skills of his fellow Canadian applicants at jobs and hence, can’t find a job.

“Their English is much better and they get preferred for jobs in my field. But then, what is the point of calling us as immigrants?”

Shlok Talati

Shlok Talati is a graduate student of journalism at the University of King's, Halifax. He has previously reported as a multimedia journalist from his hometown in India, and he continues to work as one in Canada.