In Bushra el-Fadil’s upcoming fourth novel, 2084: Sataa and Talli — a nudge to George Orwell’s 1984 — the Toronto-based columnist and poet expresses optimism for the future of Sudan, his native country.

“People build huge fences around countries like Canada, Australia, China, America,” el-Fadil told New Canadian Media, describing the setting of his novel, which takes place in a post-apocalyptic world.

But at a time when all other nations have walled themselves in, in 2084 the Sudanese people manage to create an oasis of peace, progress and flying cars — an open society at the crossroads of cultures.

“Everyone from Sudan is evacuated to two big cities on the Red sea,” el-Fadil explains.

It’s an utopia that seems worlds away from reality in present-day Sudan, a country of persistent interethnic conflict and countless coup d’états.

Weighed down

El-Fadil left Sudan in the early 1990s after Colonel Omar al-Bashir came to power. At the time, el-Fadil was teaching Russian literature at Khartoum University in the Sudanese capital. Forced out of his job for his political activism and the views he expressed in the press, he then fled to Saudi Arabia.

For decades, al-Bashir would rule Sudan with an iron fist, only to be deposed himself in a military coup in 2019. Notorious for having backed the Janjaweed militia and accused of committing genocide in the Darfur region, he is still wanted by the International Criminal Court (ICC) for war crimes.

El-Fadil describes Sudan as a country of immense natural and human wealth weighed down by bad governments, with the political situation going from bad to worse since he left.

Three years after al-Bashir stepped down, in the wake of popular protests, hopes for a democratic transition have failed. In the power-sharing agreement between civilian and military authorities, the army still holds all the cards. Last October, yet another coup repressed the pro-democracy movement there.

A ‘somewhat complicated life’

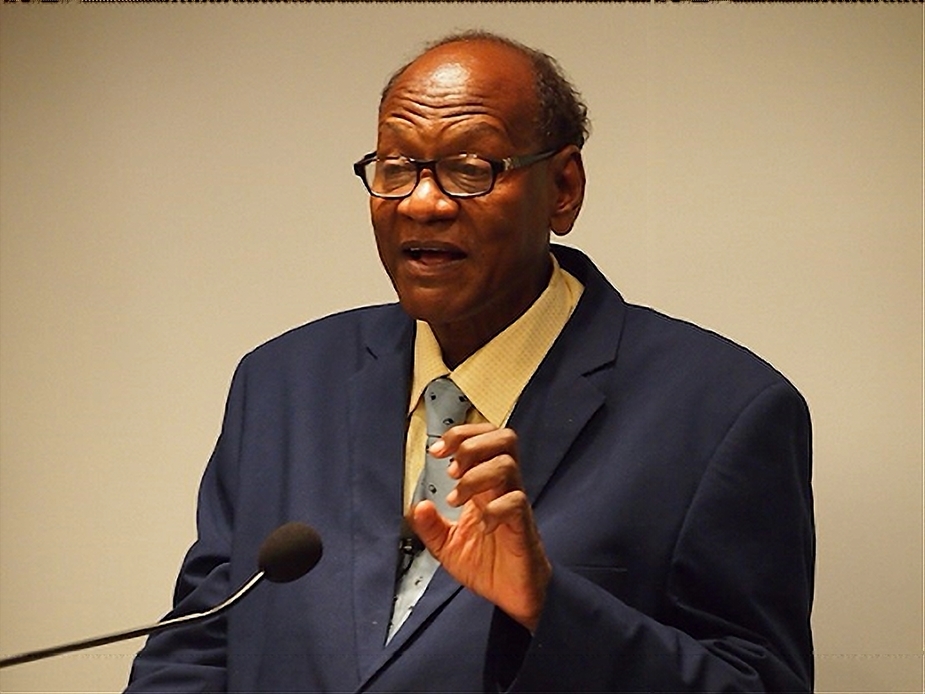

El-Fadil has penned three novels and five short stories, two collections of poetry and literary criticism, as well as numerous opinion columns.

A trained linguist, he speaks English, Arabic and Russian in addition to local Sudanese dialects. In Saudi Arabia, where he lived for many years, he worked as an Arabic language translator for various media outlets, including a stint translating electoral debates for Canadian newspapers.

“I have had a somewhat complicated life,” says el-Fadil with a smile, as he reflects on his journey.

The accomplished author completed his PhD in Soviet Russia in the 1980s. An unapologetic free thinker, he says he didn’t approve of the Marxist dogmatism of “socialist realism.” Describing himself as a jaded leftist, his political views, he admits, have softened over time.

El-Fadil is currently developing a literary “theory of everything,” which weaves together narrative and storytelling — two things that he says are central to the human experience because in everything and everywhere there are stories to be found and told.

“I write some of my stories all in my head, memorizing every line before typing the words on my computer,” he says.

Travel and exile are other sources of inspiration for el-Fadil, as are his encounters with other peoples and cultures.

El-Fadil writes mostly in Arabic. His stories have only recently been translated into English, garnering him international recognition.

In 2017, he won the Caine prize for African writing for “The Story of the Girl Whose Birds Flew Away,” where he recounts a chance encounter in a marketplace and a love story that unfolds and ends violently. The story also touches on the mental exile that comes when one’s values no longer fit with those of one’s culture of origin — a recurring theme in his work.

For example, in another novel titled Lab Oasis, he criticizes his own society as he points to the persistence of sexism and racism in Sudan, as well as a slavery system that pre-dates European colonialism, as evidence that racism is a universal problem.

In the novel, he explains, “there are Black people enslaving Black people in Sudan,” but the problem of human trafficking, especially the recruitment of child soldiers by various armed groups, persists to this day.

In Lab Oasis, set in an oasis, it takes generations for people to put an end to slavery, only to see it return. It is an old, deaf and blind woman who carries the memory of the erstwhile victory over slavery and the fragile quest for human unity.

Still in search of a publisher, the novel is being translated into English by el-Fadil’s friend, Aisha Musa Alsaeed, one of the few women politicians in the transitional democratic government that was later deposed by the October coup. She resigned in May of last year in protest against the repression and murder of civil society leaders by state forces.

A Canadian welcome

It was the Caine prize that took el-Fadil to the United States, where he toured prestigious universities as an invited lecturer, though he preferred to apply for asylum in Canada, as it was too complicated to do it there.

He arrived in Canada in 2018 and became a permanent resident in 2021, although his wife and children are still in Khartoum, the Sudanese capital, waiting for the approval of their family’s sponsorship application.

El-Fadil says Canada has welcomed him well. He is actively involved with the Sudanese diaspora in Toronto and does volunteer work on the side, teaching Arabic and translating for young Sudanese immigrants. He hopes to teach Arabic or Russian at Canadian universities and find someone willing to publish his latest novels.

Now in his late 60s, he receives disability payments for his health problems — but that hasn’t stopped him from writing.

He has participated in the group Writers in Exile, which is sponsored by PEN-Canada, and continues to publish political commentary and literary criticism for Egyptian and Sudanese newspapers. He feels much freer to write and publish about Sudan in Canada than he ever did in Saudi Arabia.

He says he looks fondly at his adoptive homeland as a place of peace and liberty, even as he reflects on Canadians’ lack of knowledge of the world outside their borders.

“But it is up to us, from countries like Sudan, to open ourselves up to the world,” he says.

The voice of Canada

“Canada is a model for other countries. In Africa and the Middle East, it is known for its humanitarianism,” he says, though it could do more to raise awareness about its actions abroad, especially among Canadians themselves.

That’s why he suggests Canada develop a dedicated world news service akin to the British Broadcasting Service (BBC) or Voice of America which would not only project a “Canadian voice” overseas, but also provide opportunities for refugee and immigrant journalists who speak multiple languages to break into the Canadian media industry.

“The voice of Canada, in all languages, is not heard,” he says, adding that Canada’s own Broadcasting Corporation (CBC) should broadcast its programming in Africa in local languages like Swahili or Arabic.

“There is an American voice in Arabic, and the French also have their voice in Arabic, but there is no Canadian voice in Arabic,” he says.

“For people like me from Arabic-speaking countries, we are waiting for the voice of Canada.”

This article is based on the results of the first Canadian study on the socio-economic conditions of first generation immigrant and refugee journalists, currently underway.

Please complete our survey on immigrant and refugee journalists here .

Having worked for a couple of years in the non-profit sector in Manila,

Christopher has written about aid and international development, human rights, immigration and armed conflict in diverse contexts. He is a member of the NCM-CAJ Collective and works as a freelance journalist.

[…] Source: Writer envisions an “oasis of peace” in Sudan […]