On paper, Prince Sibanda, a senior policy analyst with the Regional Municipality of York, and his friend Tecla, a Personal Support Worker who immigrated from Zimbabwe three years ago were a shoe-in for a two-bedroom apartment for rent at 43 Thorncliffe Park Drive in Toronto.

They had already paid first and last months’ rent — around $3,600 — had a very good credit score and a combined income of over $150,000.

Sibanda had even accepted to submit an “exhaustive banking profile” — which he found to be “very intrusive” — including emailing bank statements for the last three months.

Suddenly, after nearly two months of “jumping through hoops,” with no explanation, their application was denied.

“Within minutes of (sending the email) — and I don’t see how anyone could conceivably have even gone through the bank statements — the lady emailed me back and said, ‘application denied,'” Sibanda, also from Zimbabwe, told New Canadian Media.

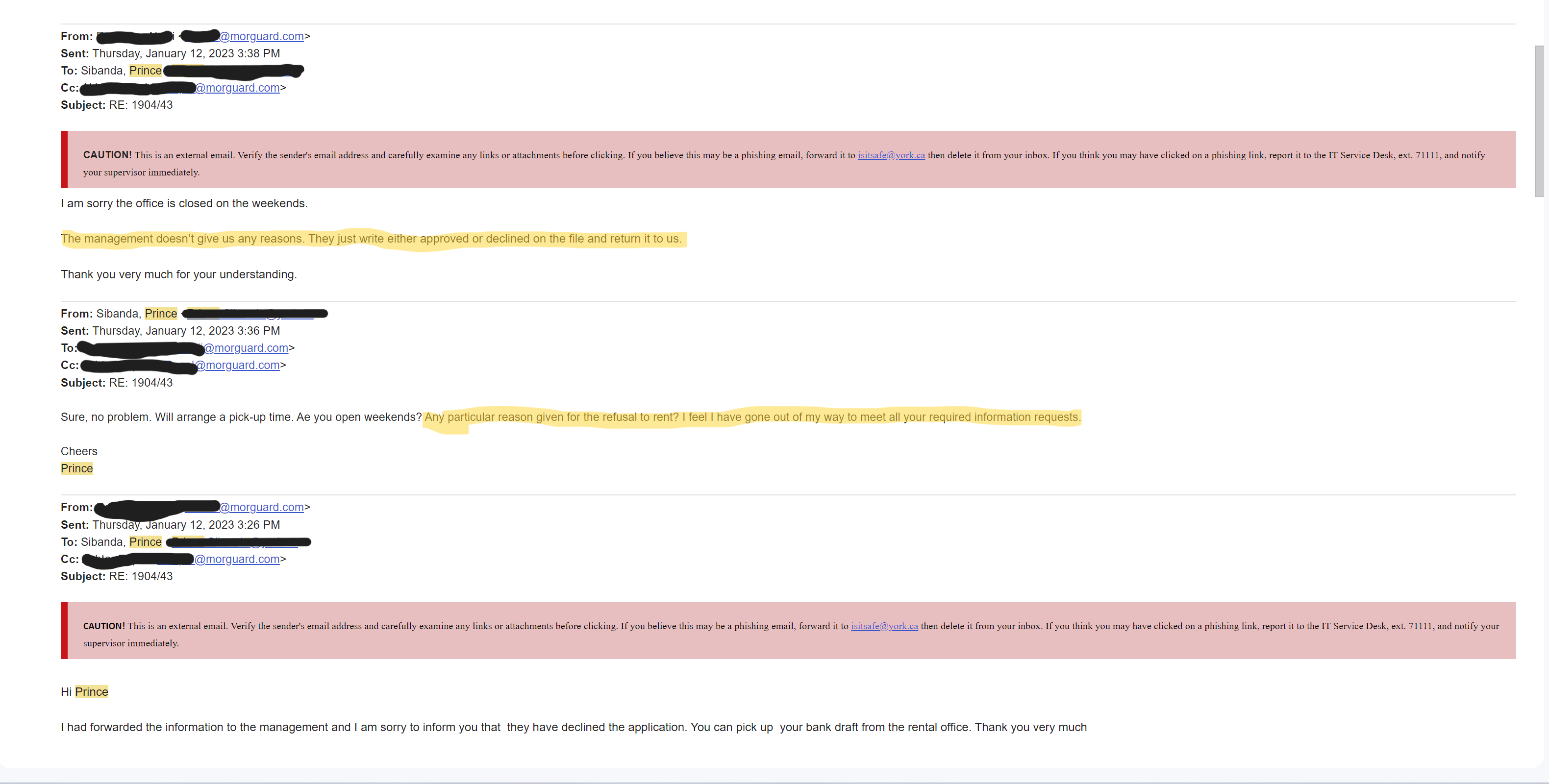

Emails between Sibanda and the rental office shared with NCM show this back and forth, with the latter letting him know on Jan. 12 that the application had been denied and to pick up the draft from the rental office.

That same day, Sibanda agreed and asked for reasons for the denial. Moments later, he received a reply saying, “The management doesn’t give us any reasons. They just write either approved or declined on the file and return it to us.”

After sending an email requesting an interview, a spokesperson from Morguard Management called NCM and said: “Due to the Privacy Act, we can’t disclose any information to anyone but the clients.”

When asked if they could confirm whether an explanation for the denial was given to either of the applicants — who claim that no explanation was given — the spokesperson said: “Like I said, that’s false. Legally, we don’t have to give a reason why…That’s according to the (Residential Tenancies Act).”

“If a file is declined, the response that is warranted is: ‘Your application is declined based on the information provided.’ That’s all that we are legally required to say.”

Discrimination study

While it’s hard to ascertain the actual reason for the denial, evidence suggests similar situations are becoming commonplace for many racialized immigrants.

Last November, a study by the Canadian Centre for Housing Rights (CCHR) found that on average, newcomers seeking a rental home face 11 times as much discrimination as non-newcomers.

“Often newcomers tell us they can find an apartment to rent, but all too often their applications are denied based on their immigration status, racial or ethnic background, the composition of their family, or because they receive social assistance,” the report states.

“Sometimes, housing providers do not say why they are refusing to rent to them, even when they can afford the unit and can provide all the information landlords are legally permitted to request.”

All this comes on top of a separate report by the Ontario Real Estate Association (OREA) in November that showed nearly two thirds (64 per cent) of Ontarians are spending over 30 per cent of their household budget on housing, with renters, on average, spending 11.2 per cent more than homeowners.

With Ontario welcoming nearly 50 per cent of all 500,000 newcomers expected by 2025 — and most of those going to Toronto — Sibanda says they can expect to see an increase in predatory practices from landlords taking advantage of both the housing crunch and immigrants’ lack of experience in it.

“So now you’re fighting on two fronts, one on being an immigrant and two on affordability,” said Sibanda, who has extensive experience as a frontline worker in the settlement field.

“So, you almost have a group of landlords that are specifically targeting immigrants during the tight housing market because they’re much easier to manipulate. And because of the shortage of (affordable) housing, they’re pretty much homeless when they arrive, so they are in a desperate situation.”

That can lead to newcomers accepting unfair or exploitative living conditions as they are often “not aware of their rights.”

The CCHR’s study conducted a “discrimination audit” — or paired testing, which matched two individuals for all relevant characteristics except for some that test for discrimination — of 1,370 units, focusing on the initial phase of phoning and emailing landlords to set up first interviews.

Hidden homelessness

The results were negative for newcomers in general. However, phone audits revealed the discrimination was much worse for racialized women who disclosed caring for a child (563 per cent); as well as men (267 per cent) and women (62 per cent) whose names or accents revealed they might be racialized.

Bahar Shadpour, the CCHR’s director of policy and communications, says the report helps put numbers to what they have been hearing anecdotally for years.

For instance, to get around allegations of discrimination or racism, “housing providers outlined stringent criteria they had to meet to rent the unit in question.”

This could include anything from asking really personal questions about family status to demanding up to six months’ rent in advance, the latter of which is a violation of the Residential Tenancies Act.

“So, in some instances, some of the stringent criteria they would outline would just outright deny the person the rental housing because it would become really unaffordable for them,” Shadpour said. “Six months’ rent in such an unaffordable rental market is out of reach for a lot of newcomers who are living on lower incomes.”

Shadpour says that though people may feel they are being discriminated against, it is “often quite subtle” and therefore hard to clearly point out, much less prove.

The audit allowed them to see this happening when, for example, “the landlord would respond really quickly to someone that wasn’t a newcomer…while they wouldn’t respond back to the other person.”

The study also had a survey component that 74 newcomer renters and potential renters responded to. Of those, 60 per cent expressed being able to find housing. However, Shadpour says even that can take up to a few years since arrival, with some having to temporarily turn to shelters in the interim.

Anecdotally, she said, they also hear that even those who do find housing may be doing so in unstable situations such as in overcrowded places or rooming houses not quite up to code.

“So they’re actually in a situation of hidden homelessness,” she said.

“Just from the reports that we hear from folks on the ground, even if they do find housing it’s not really secure long-term housing. So, there’s a possibility that they have to move again, or that they could just be evicted for no reason because they don’t have that security of tenure.”

According to CCHR’s report, of the 40 per cent who are unable to secure housing, 85 per cent earn less than $2,000 per month (before tax), 61 per cent earn less than $1,000, and 62 per cent receive social assistance.

A crisis

OREA’s report says the rising cost of living has led almost half of Ontarians (48 per cent) — including renters — to “consider making difficult choices in order to make ends meet.”

In regular hard times, this has meant refugee families may turn to the city’s temporary emergency shelter system. Lorraine Lam, an outreach worker with the Shelter & Housing Justice Network, says as many as 50 to 70 refugee families are waiting for shelter space on any single night, with an average wait of about 60 days per family.

But according to Lam, many of these families are being forced to use their own social assistance cheques to rent their own motel rooms.

“I think when people are saying, ‘The refugees and immigrants are the ones that are sort of taking up spots’ – frankly, that’s not actually what’s happening,” she said.

“There are a lot of citizens who are also in the shelter system who need housing, but at the end of the day, there is no housing so people can’t actually get anywhere…We need to actually be looking at the policies that are forcing people into certain spaces.”

Shadpour says while governments should focus on building more affordable housing in the long-term, an immediate solution ought to concentrate on preserving the current affordable housing stock.

“We really need to be able to maintain and preserve the older purpose-built apartment rentals that we have, because that’s where a lot of folks go as the rents are comparatively lower than condominiums and housing within the secondary market.”

Other recommendations in the report include setting up no-fee guarantor services to support newcomers to access housing upon arrival in Canada; opening investigations into discriminatory practices and solutions; and working collaboratively among all levels of government to “develop, encourage, and promote education for tenants to learn about their legal rights and for housing providers to learn about their legal obligations.”

For their part, Sibanda and his friend Tecla have not had to turn to the shelter system, though most of Tecla’s belongings are in storage until she finds a new apartment.

In the meantime, Sibanda will continue working with her and other newcomers to help them find affordable and suitable accommodations — but without government intervention, that’s becoming increasingly harder.

“The most vulnerable within our community right now, in terms of housing, are pretty much in desperate conditions,” he said.

“Yeah, it’s a crisis.”

Fernando Arce is a Toronto-based independent journalist originally from Ecuador. He is a co-founder and editor of The Grind, a free local news and arts print publication, as well as an NCM-CAJ member and mentor. He writes in English and Spanish, and has reported from various locations across Canada, Ecuador and Venezuela. While his work in journalism is dedicated to democratizing information and making it accessible across the board, he spends most of his free time hiking with his three huskies: Aquiles, Picasso and Iris. He has a BA in Political Science from York University and an MA in Journalism from Western University.