The battle for southwestern Ontario is shaping up to be a pitched battle between rural and urban voters, with the Conservatives particularly vulnerable in six ridings throughout the region, researchers say.

“For sure at this point I think there are at least six ridings that we should be watching and notably they are in urban centres,” said Anna Esselment, an assistant professor of political science at the University of Waterloo who studies election campaigns.

“The Conservatives are going to do relatively well in rural areas, as they have in the past. That seems to be the way things are shaping up.”

Five researchers contacted by iPolitics all agree that the Conservative-held ridings of Kitchener Centre, Waterloo, London North Centre, London West, Oakville, and Oakville-North Burlington are all at risk.

Esselment notes that all have particularly strong Liberal contenders who could benefit as public opinion pulls away from the NDP and focuses on a contest between the Conservatives and the Liberals, as recent polls have indicated.

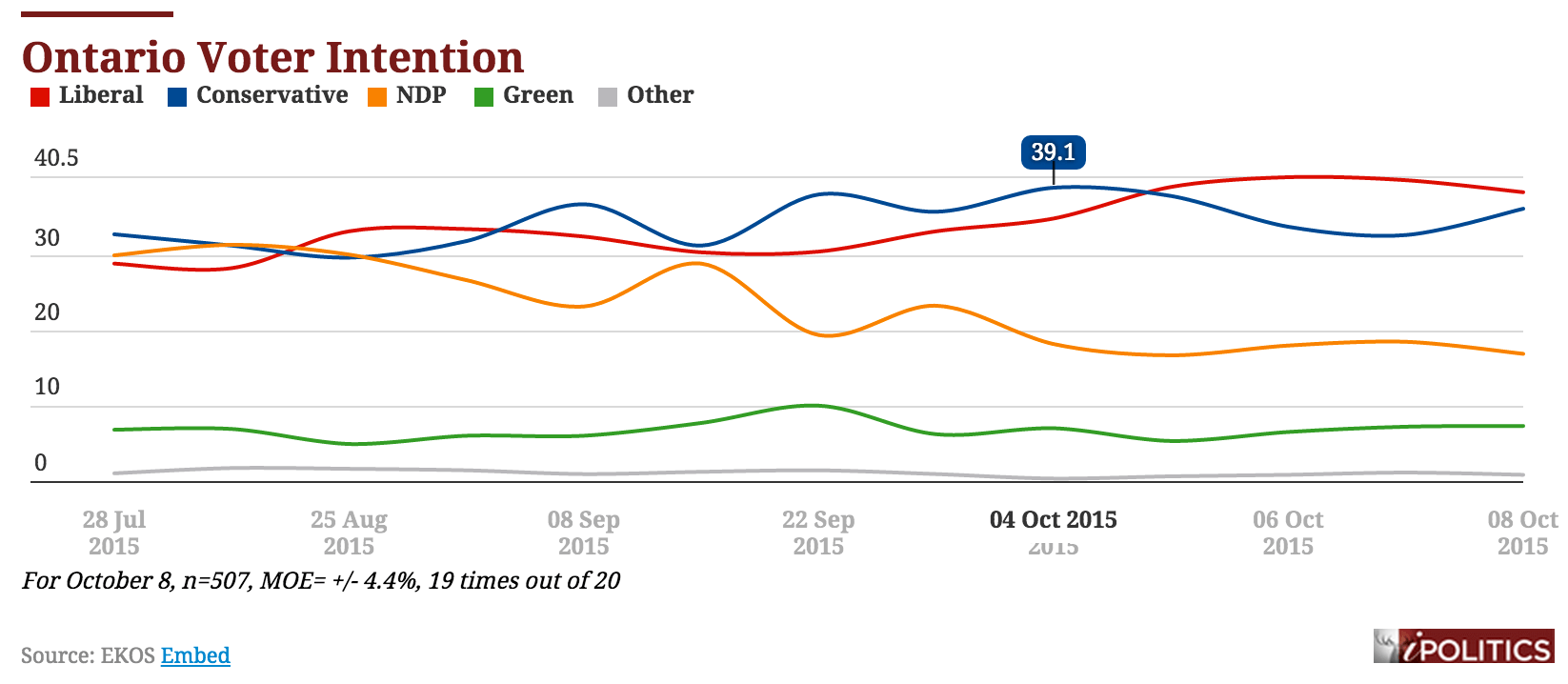

[T]he Liberals [are] polling as high as 40 per cent [in Ontario] in recent days.

Dubbed the ‘Orange Crash,’ support for the NDP has plummeted from a virtual three-way tie at the start of the campaign to a tie between the Liberals and Conservatives, with 31 and 33 per cent respectively, and the NDP struggling to crack 20 per cent support.

In Ontario, the trend is even more pronounced, with the Liberals polling as high as 40 per cent in recent days.

“That was a three-horse race nationally, never really regionally,” said Kimble Ainslie, president of Nordex Research, a public opinion and market research firm based in London, Ont.

“In Ontario, basically it was the Tories and the Grits with perhaps the NDP coming close third.”

Political history of the region

The six urban ridings at play in southwestern Ontario aren’t traditionally Conservative. Oakville was held by Liberal Bonnie Brown for a decade before bouncing to the Conservatives in 2008, while Halton — now subdivided into Oakville-North Burlington and Milton — has fluctuated between Grits and Tories consistently since Confederation.

London North Centre went Conservative for the first time in 2011 but was held consistently by the Liberals since 1997, while London West turned blue for the first time in 2008 after being held exclusively by the Liberal since 1968 – save for 1984 to 1993, when it was won by the Progressive Conservatives.

“The Conservatives are weaker this time and the Liberals are stronger this time than they were last time.”

Kitchener Centre had also been Liberal since its creation in 1997 until Stephen Woodworth won it for the Conservatives in 2008.

Waterloo is a new riding – it existed from 1968 to 1997 but was redistributed into Kitchener-Waterloo and Waterloo-Wellington. The new Waterloo riding is made up of most of the old Kitchener-Waterloo riding, which also went Conservative for the first time in 2008.

Economic stability, unemployment top of mind

However, a lot has changed since the 2008 election, not least among them, the crash in manufacturing that has cost hundreds of jobs throughout the region, particularly London and Windsor.

“The Conservatives are weaker this time and the Liberals are stronger this time than they were last time,” said Peter Woolstencroft, an associate professor of political science at the University of Windsor.

Woolstencroft says the Conservatives have taken hits to their economic record lately, one of the most important issues for voters in the region.

Statistics Canada released its September Labour Force Survey on Friday, which shows growth in the manufacturing sector remained flat compared to this time last year.

As well, it showed unemployment rates in London, Windsor and St. Catharines are at five-month highs.

The Trans-Pacific Partnership has also sparked concerns over its potential impact will be on the automotive and dairy industries — both large employers in the region.

“Unemployment is top of mind, the restoration of what used to be a fairly stable, reliable economy,” said Cristine de Clercy, an associate professor of political science at Western University.

“I think that there’s an agitation among voters that they want a different direction, that they may be unhappy with the fact that the economy is not growing as quickly as they’d like it to.”

Lydia Miljan, an associate professor of political science at the University of Waterloo, says while she agrees there are opportunities for Conservative upsets, she doesn’t think the recent unemployment numbers will be a particular cause for concern among regional voters given that they were linked to factors largely outside of government control.

“A lot of the job losses are sort of, at least in the past, the ones we had sustained because of the recession, had more to do with the rising dollar than any specific economic policy,” she said. “The problem is that we really haven’t recovered as quickly as a lot of people would like.”

In the ridings around Oakville and parts of Waterloo, unemployment is not as significant a problem as in Windsor and London but there are still challenges that will play into voters decisions.

Youth in Oakville are facing unemployment rates of between 17 and 20 per cent, far above the provincial average of 13 per cent, and the local chamber of commerce said that was one of the main concerns raised by residents ahead of a local all-candidates debate last week.

In Waterloo, Woolstencroft says the availability of plenty of high-tech jobs doesn’t solve the dearth of blue collar jobs and that those without a university education are still struggling to find work.

Ultimately, researchers say the votes will come down to the vision residents have for the future of their communities — the economic stability they want for themselves and the economic opportunities they want for their children.

“I think that there’s an agitation among voters that they want a different direction, that they may be unhappy with the fact that the economy is not growing as quickly as they’d like it to, agitation over whether they’ll have a job from now, or two years from now, agitation over whether their children will have the opportunities they had when they were coming out of university,” said Esselment.

“I think people are agitated by the state of things and that can make them think a little more about the choices that are in front of them.”

Published in partnership with iPolitics.ca.