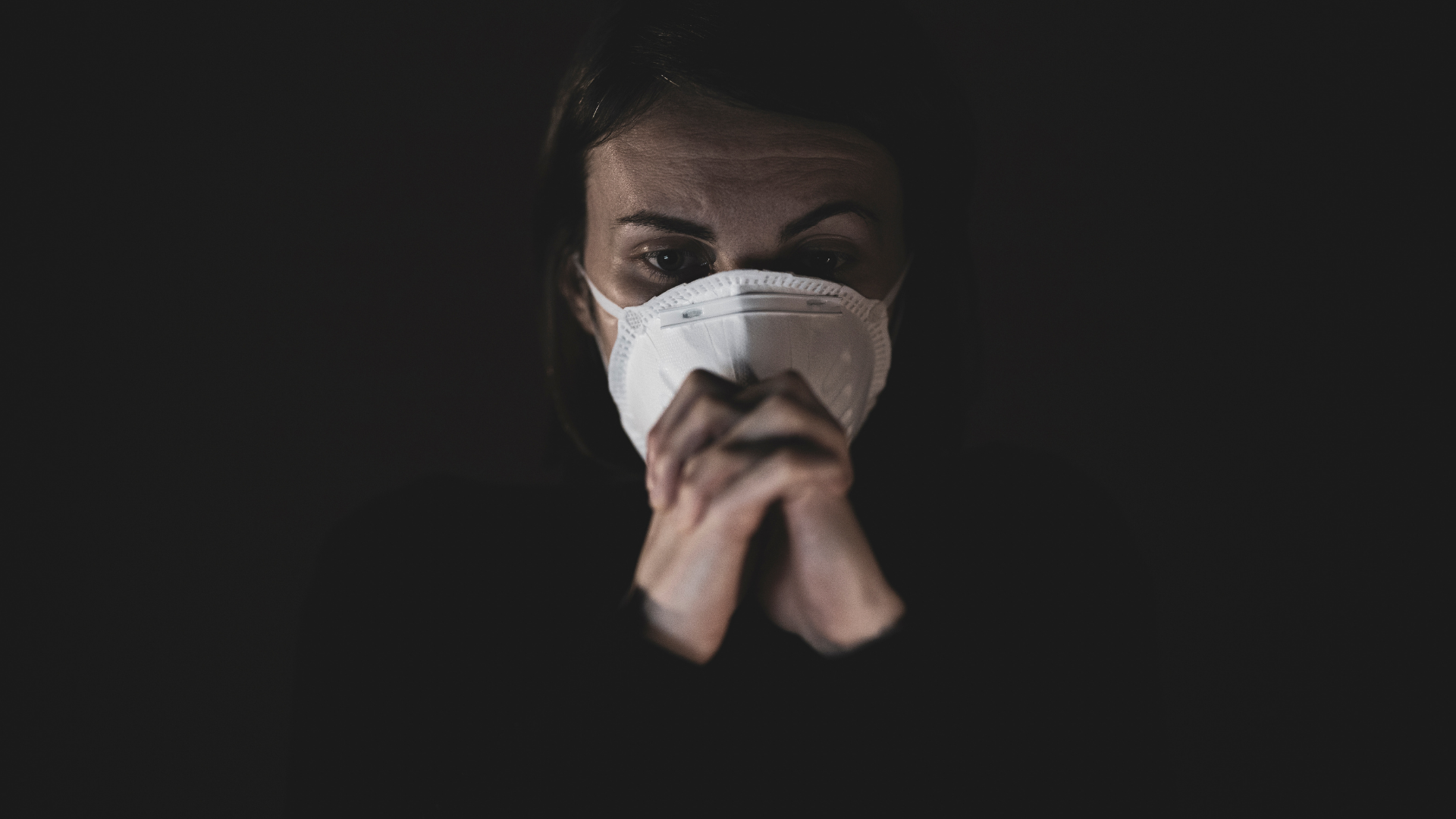

Lockdowns and physical distancing measures in place because of the pandemic mean that this winter the seasonal affective disorder (SAD) is compounded by feelings of isolation and loneliness, leading to a spike in mental health issues among Canadians.

Closures to fitness centres and the cancellation of recreational sports mean that people aren’t as active as usual. The cocktail of chemicals released when you exercise regularly helps people sleep well, deal with stress, improve their appetite, and boost their overall sense of well-being.

But lockdowns aren’t just keeping people from the gym; they’re keeping people from each other. Studies show that loneliness is correlated with higher levels of the stress hormone cortisol. Consistently high stress levels make people more susceptible to health issues like heart or cardiovascular disease as well as cancer. Plus, stress can slow down recovery time.

Humans literally need friendship and interaction, even chance interactions and conversations with acquaintances, but right now there’s a dearth of it.

Parents have lost connection to the proverbial village needed to raise children. And it’s not an exaggeration to say that children have lost an irreplaceable year of their youth. I imagine it’s especially difficult for young-immigrant children still adjusting to life in Canada.

Thousands of Canadians have experienced job loss or a reduction in work hours over the course of the pandemic. Even those fortunate enough to be working or have transitioned to a work-from-home arrangement have learned that it isn’t a perfect solution.

All of these things contribute to deteriorating mental health and this is by no means an exhaustive list. According to the Canadian Mental Health Association (CMHA), each winter 15 per cent of the population experience a milder form of seasonal affective disorder (SAD) that leaves them feeling slightly depressed. While we may be more than halfway through winter, the pandemic isn’t going away anytime soon.

Pandemic’s mental health toll on Canadians

In any given year, one in five Canadians deals with an addiction or a mental health issue. And as we’ve learned about most bad things, the pandemic’s made it worse. Pre-pandemic — if you can remember that far back — 2.6 per cent of Canadians experienced suicidal ideation. That number rose to 6 per cent in May, when CMHA conducted its initial survey, and it shot up to 10 per cent in September. Now that we’re only a few weeks away from the anniversary of living with COVID-19, amidst talk of a potential third wave, I don’t even want to think about what that number is now.

please don’t ask me HOW i am pic.twitter.com/qNZQK9vbgK

— miski 🛸 (@musegold) February 12, 2021

Certain segments of the population are more likely to experience mental health challenges during the pandemic. Specifically, women, single parents and parents with school-aged children, students, Indigenous people, the LGBTQ2S community, and people with pre-existing mental health conditions. They’ve all reported deteriorating mental health at a higher rate than the rest of the population, according to the CMHA study.

According to the Public Health Agency of Canada, men account for 75 per cent of suicides in Canada. Many of the determinants of mental health issues, including substance abuse and suicide, disproportionately affect men and boys. Those factors include losing your job or your sense of purpose and pride, low education or dropping out, not having close friends, and loneliness.

Without minimizing the seriousness of these statistics, I imagine that everyone is a little more susceptible to those mental-health factors nowadays. The classic tells of depression — pessimism, a loss of interest, changes to sleeping or eating patterns, anxiety — have become some people’s default during the pandemic. Now more than ever it’s important to check in with your loved ones and be honest about how you’re feeling.

How we handle mental health

Unfortunately, more and more people turned to substances to cope with their feelings during the pandemic. There’s been more drinking, more use of psychedelics and more overdose deaths. Some see substance use as a more accessible alternative for dealing with their thoughts and feelings than counselling or therapy.

Free mental health resources and supports are available, but the wait times can be too long. This is especially true for post-secondary students attempting to access their schools’ services. And like most health conditions, early intervention often leads to better outcomes.

Affordability is also an issue for many people because privatized care can cost between $100 and $225 an hour. If you’re still working, there’s a chance you have access to an employee assistance program (EAP) through your employer. EAPs provide employees with free resources like mental-health focused webinars, access to short-term counselling, and professional mental health recommendations.

However, in some families mental health issues are a taboo subject and admitting to having one is a sign of weakness. Some religious communities believe mental health challenges can be overcome by faith, or that they’re a form of punishment. Some people don’t even acknowledge mental health issues as something that needs to be addressed. To combat those ideas, some experts suggest people think of mental health issues as part of the human experience rather than a deviation from it.

Finding mental health supports

There are some people who recognize mental health issues and want to address them but don’t feel comfortable seeking support. Some BIPOC want the help of mental health professionals with the same ethnic or cultural background as them, in the hopes that these professionals will understand the customs and nuances that influence their lives. Professionals with this deeper cultural understanding are better equipped to suggest culturally appropriate solutions for their clients.

The fact that BIPOC and people from marginalized communities regularly deal with microaggressions is all the more reason to seek mental health support. It’s been proven that microaggressions can make people feel undesirable, abnormal, invalidated, insulted, or angry. Microaggressions are associated with increased anxiety, depressions, stress and other health concerns.

Getting started

Tackling mental health issues is never easy, and often involves constant work, but it’s crucial.

Meditation and mindfulness practices are a good start, although they may not be enough on their own .They can however help people form good habits and thought patterns. There are also programs like MindBeacon, Bounce Back, and the federal government’s Wellness Together program. Telemedicine and services like Kids Help Phone or Good2Talk are excellent free resources for students.

I used to do a 23-minute-daily-morning routine and I found it incredibly helpful, but there’s no one-size-fits-all solution. It’s important to access mental health supports appropriate to your needs.

World-renowned family therapist Virginia Satir once said, “We need four hugs a day for survival, eight hugs a day for maintenance and 12 hugs a day for growth.” But with physical distancing protocols in place, getting one hug — let alone 12 — seems unimaginable. Since we can’t access our usual communities and mental health supports, it’s important that we find alternatives.

Marcus is a poet, editor and freelance journalist based in Toronto. He currently works with New Canadian Media as an Editor and as a Freelance Writer for ByBlacks.com, The Edge: A Leader's Magazine and The Soapbox Press.