Q. As an immigrant policy expert, what did you think of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) calling Canada’s intake system a “BENCHMARK” for the rest of the world?

A. Largely correct. Canada tends to encourage and manage economic immigration well, ranging from relatively objective and transparent criteria through Express Entry/points system, one that provides flexibility to adjust as required.

Associated policies and programs, such as settlement services and an accessible path to citizenship, are contributing factors.

Extensive datasets and evaluations help officials understand how well programs are working or not, an example being the previous business immigration program which was cancelled under the previous government based on poor results.

Public support for economic immigration is high. No major political party is anti-immigration.

The report correctly identifies foreign credential recognition as an ongoing issue, one that successive governments have tried to address with limited results to date (provincial certifying bodies).

The call for streamlining Express Entry through merging the Federal Skilled Worker program with the Canadian Experience class makes sense, as government programs often emerge to address specific needs. Periodic review to assess whether complex set of individual programs remain relevant or not is a good program management practice (sometimes easier to create a new program than integrate or streamline existing programs.

Related reports such as the OECD integration report indicate that strong economic (e.g., participation and employment) and social (e.g., integration), although some more recent immigrants and some visible minority groups struggle.

Q. This accolade comes on the eve of a federal election, which some experts say may be the first national campaign in which immigration proves to be a truly divisive issue. Do you see immigration emerging as a wedge issue?

A. Only one party, The People’s Party of Canada (PPC), is specifically campaigning on immigration, with its call to cut immigration by between half and two-thirds and repeal the The Canadian Multiculturalism Act. Conservative party criticism focuses more on administration and management issues, particularly the asylum seekers crossing at Roxham Road. Leader Andrew Scheer’s immigration policy announcement, while light on details, nevertheless made a strong statement on inclusion. However, their strong opposition to M-103 on Islamophobia and the Global Compact on Migration are signals of a somewhat more restrictive approach to immigration-related issues.

Given the large number of ridings in play with significant numbers of immigrants and visible minorities (41 ridings are majority visible minority, another 93 have between 20 and 50% visible minorities), hard to see how a successful political strategy can be expressly anti-immigration.

That being said, there will be considerable virtue signalling and identity politics by all parties, with likely some flirting with anti-immigration/anti-multiculturalism sentiment and some painting concerns about high immigration levels and the like as xenophobic and racist.

But not convinced that it will become a major wedge issue given electoral realities.

Q. What do you think of this often-reported “immigrant vote” or “ethnic vote” — especially in and around Toronto and Vancouver — playing a decisive role in national elections? What does your analysis show?

A. The tables at left show how visible minorities are reflected by province and ridings along with the number of ridings where individual visible minority groups form more than 10% of the population (electorally significant).

There is no one immigrant or ethnic vote. Voting preferences vary depending on the time of arrival (generally earlier waves of immigrants lean more to the Conservatives in contrast to more recent waves). While there are some general preferences between groups, there are differences within each group as well. No party has a monopoly of these voters, and preferences can shift between elections and thus all parties make efforts to win voters in these ridings through candidate selection, policy development and campaign strategies.

Given the large number of ridings in play with significant numbers of immigrants and visible minorities (41 ridings are visible minority majority, another 93 have between 20 and 50% visible minorities), here is no road to a majority government without winning most of these ridings (for the most part, the 905 in the Greater Toronto Area and B.C.’s lower mainland).

These ridings can shift dramatically. For example, the Conservatives made major inroads among immigrants, helping them achieve a majority in 2012, only to lose most of those ridings in 2015 to the Liberals. In the 2018 Ontario provincial election, the Progressive Conservatives won most of the Ontario visible minority majority ridings from the Liberals.

MIREMS (Multilingual International Research and Ethnic Media Services) and I developed diversityvotes.ca to match riding-level demographic and socioeconomic characteristics with ethnic media election coverage with a view to facilitate:

- More in-depth understanding of riding characteristics, and how these interact with electoral strategies;

- Wider awareness of how national and local issues are portrayed in community and regional ethnic media to increase accountability of ethnic-oriented media strategies;

- More informed discussion regarding ethnic voting patterns and issues, and;

- Greater responsibility of candidates and political partiers of their messaging to different groups.

Q. We know you are also a number-cruncher, one who takes a close look at data. In terms of candidate diversity, what are the trend lines looking like?

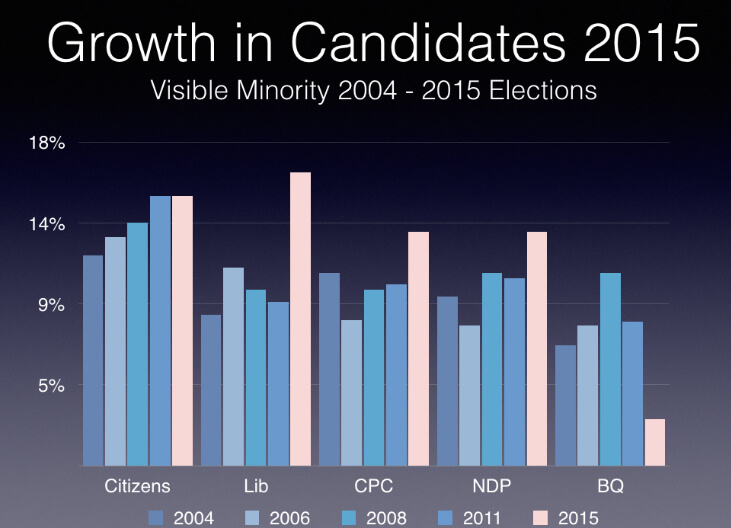

A. Too early to be definitive as not all candidates have been nominated, with the Liberals significantly behind the Conservatives in terms of nominations. Working with a number of other researchers currently to see whether the 2015 trend of greater diversity among the three major parties continues or not. The chart at left captures the change in 2015.

Q. Populism is seemingly driven by an underlying anti-immigrant sentiment. Do you see anti-immigrant sentiment rising in Canada? Or, do you see us as quite distinct from virtually every western nation?

A. While Canada is not immune to global trends, long-term tracking shows majority support for immigration. While there are concerns regarding the numbers of immigrants and the mix between economic, family and refugee classes, the three major parties are all strong believers that immigration is a net benefit to Canada.

The Conservatives tend to favour more restrictive policies, reflecting their base, than the Liberals or the New Democratic Party, but this is a matter of degree, not fundamentals. Much of the focus of Conservative attacks on the government’s immigration policies is on management of the program, where the irregular asylum seekers crossing the border in Quebec are cited as a failure.

The PPC, the only national party to run on an explicit restrictionist immigration (and multiculturalism) policy, appears stuck at around 3% of voter support at this early stage.

Polling data shows greater public concern regarding adherence to Canadian values, typically in relation to accommodation for religious minorities.

Quebec is different from the rest of Canada in this regard, as seen by the strong support for The Coalition Avenir Québec government’s dress code requirements for public servants and employees and its perennial debates and discussion regarding accommodation issues.

In the end, the electoral realty that one cannot win a majority government without support from immigrant and visible minority voters limits the attractiveness of populism based on anti-immigrant views.

The two leading populists, Ontario’s Doug Ford and Alberta’s Jason Kenney, are not anti-immigrant and frame their populism largely around economic issues.

Andrew Griffith is the author of Multiculturalism in Canada: Evidence and Anecdote, Policy Arrogance or Innocent Bias: Resetting Citizenship and Multiculturalism and many other works. He is a former Director-General of Citizenship and Immigration Canada, Citizenship and Multiculturalism branch. He regularly comments on citizenship, multiculturalism and related issues, in this blog and the media.