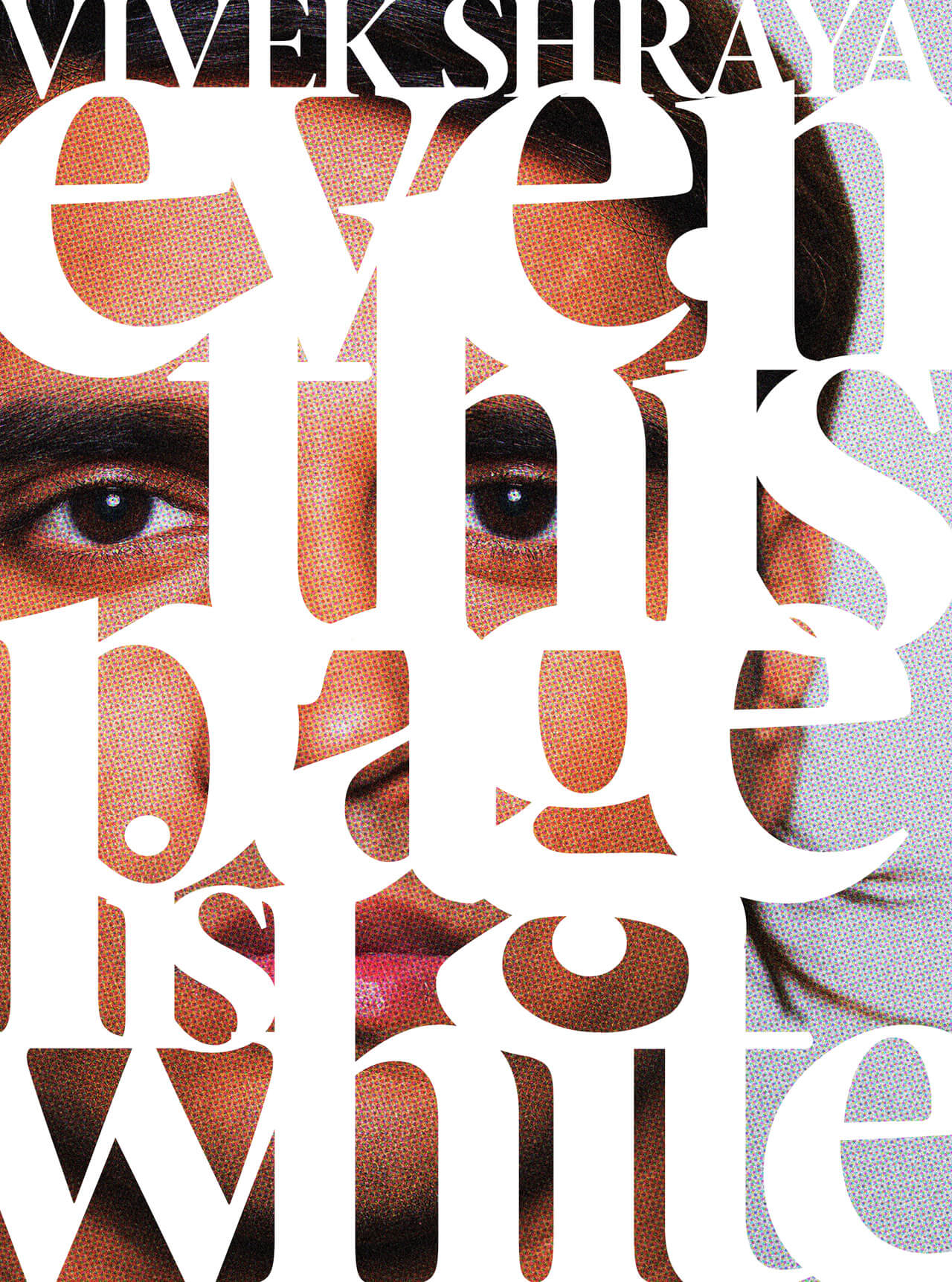

Vivek Shraya does not mince words. In even this page is white, her language is visceral, and even the form of her poetry helps to draw attention to the sensitive issue of racism.

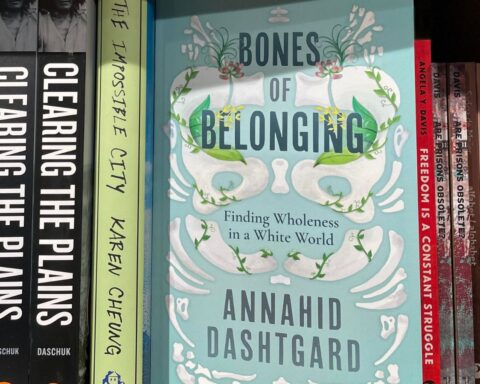

Most of the poems in even this page is white are written in the style of spoken word poetry, and as such, the words can be quite shocking and blunt. Shraya’s debut collection of poems focuses on the physical entity of skin and racism, centring on the idea of being white and drawing upon current events and modern poetry.

Conforming to racial roles

She begins with her “white dreams,” describing how she was raised in a society that is predominantly white and how she tries to fit in. In exploring the idea of identity, Shraya includes the perspectives of a white person.

She explores the word “skin,” its physical element, and its function. She points out that within “white,” there are a range of colours, such as fair and talc.

The text hints at how Shraya must also conform to white society’s expectations before her views on racism can be heard.

In the poem “You are so articulate,” she explains that there is a standard she must meet in order to be considered normal in mainstream society. The poem is a checklist of steps that minorities are expected to follow in order to be considered successful in North American culture.

The text hints at how Shraya must also conform to white society’s expectations before her views on racism can be heard.

In another checklist, Shraya reveals the things she, her mother, and her father had to do so that she could become a poet and express her thoughts in writing. Her father, for example, worked three jobs and sacrificed time with Shraya as a child to pay for her post-secondary education.

The more the world makes her aware of her brownness, the more she focuses on how race and racism are connected to every aspect of her life. She writes about the ways her race intersects with her desirability, her desires, her gender, her religion, and how she connects or doesn’t connect with others.

Deciphering popular messages

Deciphering popular messages

Shraya questions the actions of celebrities who have also confronted the topic of race through their work. In one poem, she lists reasons why Kanye West should be banned from performing at the Pan American Games closing ceremonies, which took place in Toronto, Ont., in 2015.

Most of her reasons attack West’s character with words like “selfish” and “childish,” but also attack his talent, describing him as a terrible musician. The most interesting accusation against West is that he “will turn the games into a racism issue.”

It seems ironic that Shraya critiques him this way, when she seems to view most things through the lens of race as well. Shraya says her goal was to highlight how seemingly inoffensive and dismissible pop culture moments speak to systematic racism.

The more the world makes her aware of her brownness, the more she focuses on how race and racism are connected to every aspect of her life.

In “Oscars So White,” she draws on the controversy of celebrities boycotting the Academy Awards for not nominating more non-white actors. In this poem, she points out contradictions, questioning whether the Academy should start nominating more non-white actors simply because of their skin colour.

In another examination of miscommunication, Shraya describes the sounds heard at a Gay Pride event on June 24, 2015 – the voices of protesters, police, the main speaker, and those who were trying to silence the message.

The main speaker’s message makes up the bulk of the text, but there are other voices present in the margins. Imagine the main speaker being talked over by the police, while listeners are shushing and trying to compete with the authorities to listen to the message.

Working together against racism

In the middle of the book, Shraya records a discussion she has with four white women regarding racism, focusing on their white privilege, their awareness of other races, and their reaction to racism. One admits she recognizes that she is undereducated about anything outside “the white gaze” and “under-practised in talking about racism.”

In the end, Shraya says the most important thing is that a person listens and takes action against racism.

The interview is interesting because most stories about racism are shared from the perspective of those who are targeted. These white friends of Shraya recognize there is a disparity between races, but admit they are sometimes afraid to do anything about it or not sure what to do in response.

The author asks her friends to make an “allyship towards people of colour,” suggesting the need for white people to support the idea of eliminating racism or racist attitudes, rather than being divided against people of colour.

In the end, Shraya says the most important thing is that a person listens and takes action against racism. She doesn’t indicate what kind of action, but that people should start by communicating to come to an understanding of the problem of race-based discrimination.

While Shraya starts with discussing white dreams, she ends with brown dreams – the need to justify the pigment of her skin. In her note at the end of the book, she states that she wants this book to act as a catalyst for discussions about anti-black racism, as well as racism towards indigenous people who continue to face racial violence.

Florence Hwang used to work as a print journalist before becoming a media librarian. These days, she is also a freelance writer, whose work has been featured in several publications, including New Canadian Media. Outside of work, Florence spends her time making short films about her family history.

Florence Hwang is a Saskatchewan-based freelance writer. She is a media librarian who loves storytelling. She has written for La Source newspaper, CBC Saskatchewan, Saskatchewan Folklore and South Asian Post.