While Canadians struggle to find a health care professional, foreign-trained doctors continue being put through a cumbersome accreditation process that includes having Canadian experience and references most newcomers don’t have.

The process includes passing the Medical Council of Canada Qualifying Examination, an exam to assess their ability and medical knowledge of a candidate.

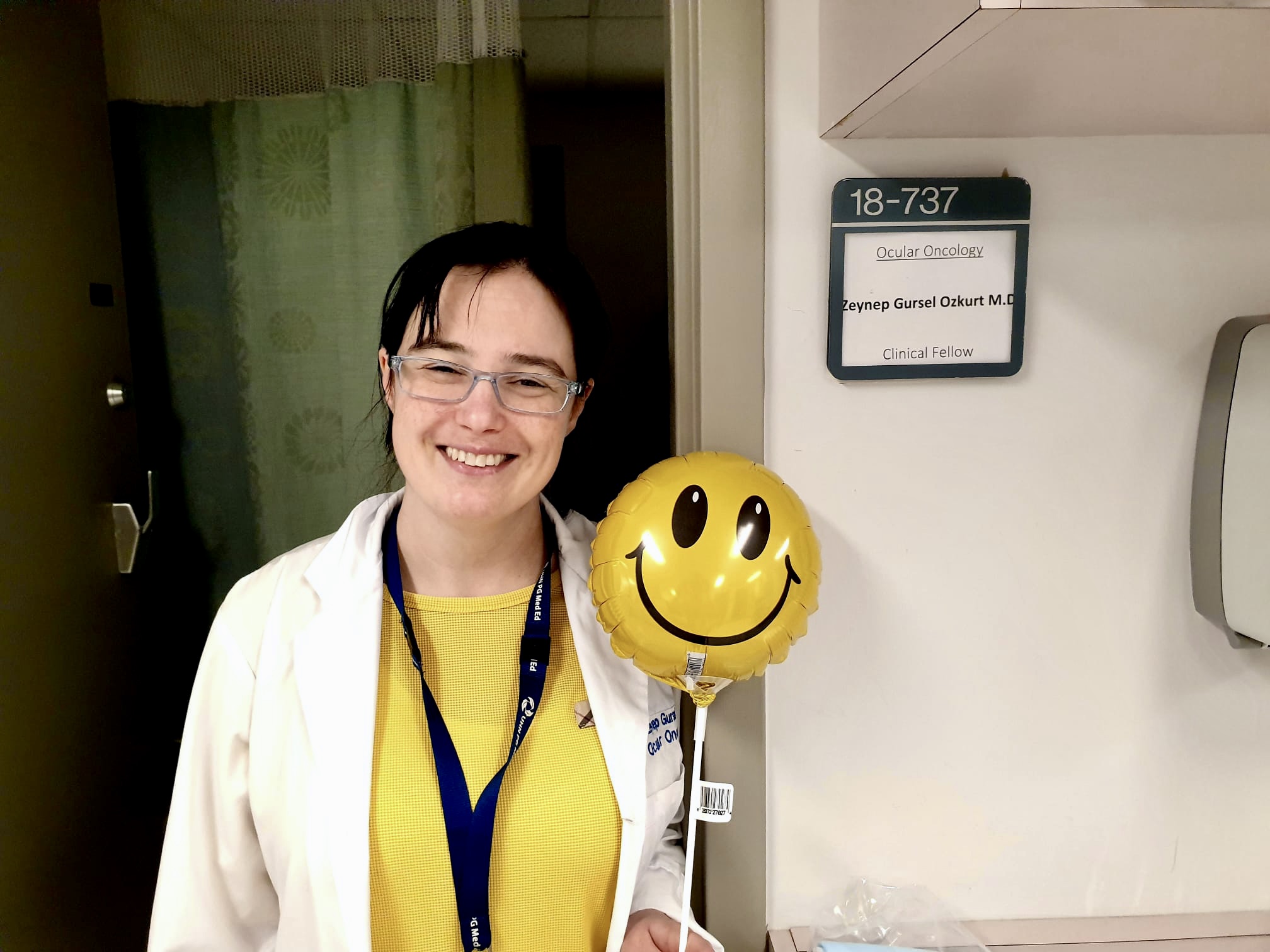

“But, unfortunately, even if you pass the exams, there is … very little chance for you to get a residency (spot),” Zeynep Gursel Ozkurt, a former ophthalmologist MD, told New Canadian Media.

“There are very few quotas, and they only get whoever has the strongest reference….(But) it is really hard to find a Canadian reference for a foreign doctor.”

She was reacting to last fall’s Ontario legislation to help reduce some of the more stringent demands on newcomers, including the Canadian experience requirement, but the changes are not expected to occur for another two years.

Meanwhile, while campaigning ahead of the June 2 provincial election, the Ontario New Democratic Party (NDP) has said it will work with the College of Physicians and Surgeons of Ontario to expedite the process for international medical graduates to obtain their licence to work in Northern Ontario.

But the changes can’t come soon enough — not for the thousands of professionals who’ve been relegated to survival jobs nor for the patients going without a doctor.

No doctors

According to the Physician Data Centre of the Canadian Medical Association, as of January 2019, there were 86,092 active physicians — excluding those in residency. This translates to “2.41 physicians per 1,000 population,” the report says.

Another report from the Commonwealth Fund found that Canada ranked ninth out of 11 high-income countries in terms of access to health care, with Netherland, Norway, and Germany in the top three.

Based on Statistics Canada Canadian Community Health Survey 2019, 14.5 per cent of the population (older than 12 years) does not have a regular health care provider such as a family doctor, medical specialist or nurse practitioner.

“Canada suffers from a shortage of doctors, nurses and health professionals, which means patients do not always get the level of care they deserve,” Minister of Heath Jean-Yves Duclos said in a Mar. 23 statement.

“However, there are internationally trained health professionals in Canada who would be willing to work, but their training is not recognized here in Canada. Thanks to the Foreign Credential Recognition Program, they will be able to get their credentials recognized and contribute to addressing our urgent healthcare needs,” the statement said.

Feeling hopeless

Esra Karakaya is a dentist who immigrated to Canada four years ago after studying “for at least nine years — except for work experience — to be a dental specialist at one of the most famous medical universities in Turkey.”

But now, she says, “it has no value here.”

Karakaya says in her time here, she’s met people who have “travelled to their country for treatment” after waiting for months just to try to see a specialist

“If there are fewer specialists, they can make the system easier and employ us,” she says.

“I was hopeless about my future when I came to Canada, because I could not solve the system, but now I lost hope that I could do my job.”

She says dentists also must take exams to get a licence in Canada. However, the exams are too expensive and the requirements too stringent.

“The most significant barrier is the interview after the exam because you must have a strong reference to be accepted,” Karakaya explains.

After immigrating to Canada, Karakaya applied for volunteer work to learn the system. Yet, she could not get any response

“At least, they can observe us, or just let us work voluntarily to encourage,” she says. “This step will help us to adapt to the system.”

Struggling in Canada

Similarly, Ozkurt was working since 2005 as an assistant professor and later associate professor in Turkey and studied ocular oncology at the University of Michigan. In 2019, Ozkurt came to Canada for a clinical fellowship program, and she was accepted by the Princess Margaret Cancer Centre at the University of Toronto.

However, because of political issues in Turkey, Ozkurt and her family could not go back to their homelands. Now, they are struggling to maintain their professions in Canada.

“I do not have a medical license in Canada. I only have an ocular oncologist licence today. I can work as an ocular oncologist, but I cannot treat patients such as cataract patients, coronary patients, or oculoplastic patients,” she says.

“Ocular oncology is not a very popular department, and there are only three centres in Canada which now do not require any more staff. … So, I cannot work as a doctor.”

Ozkurt has been hired for a project as a researcher for one year, but after that, come October 2022 she says, she “will be jobless.”

Ozkurt’s husband is also an otorhinolaryngologist, and he performed facial aesthetic surgeries in Europe. However, he also cannot work as a physician in Canada because he also has not been able to get strong references. As a result, says Ozkurt, he’s been working as an Uber driver for nearly three years..

Government’s announcement

The federal government announced on March 23 that it is investing in projects to prioritize getting skilled newcomers in the health care sector, and they will help them get the required education and skills to work sooner

In a separate joint statement released on May 1, on National Physicians’ Day, the federal government said it will provide $115 million to help foreign-trained health care professionals get their credentials recognized and find jobs in their fields in Canada. But it remains unclear when this decision will be implemented.

“It is not about trust, because I have already seen a lot of doctors here. I have worked in the ocular oncology field. I can reassure you that we are as good as them,” Ozkurt says, referring to doctors trained in Canada.

“We are as experienced as them, and our knowledge has not taught us less than them.”

Read also: Even During a Pandemic, Immigrant Doctors Struggle to Find Work

Nur Dogan is a Turkish journalist who lives in Toronto. She studied journalism at Humber College. Her stories and photographs were published not only in Canada but also in the U.S. and Europe. As a digital media reporter, she has covered national and international news for some magazines, newspapers and online news platforms. Focusing on human rights for all, Nur observes and reports on human rights violations, oppressions and illegitimate political attempts against visible minorities.