Early in the pandemic, Adelina Petit-Vouriot logs on to Zoom. The familiar blue logo pops up as it loads the meeting. She’s helping host a Zoom webinar with Canadian political interns for the Samara Centre for Democracy, a non-partisan research charity. About 20 minutes in, they’re Zoom bombed.

Petit-Vouriot said she believes it wasn’t targeted. “As far as I know, it was completely random that someone showed up. They played loud music, they drew some crude images on the screen, and we were able to shut it off in seconds.”

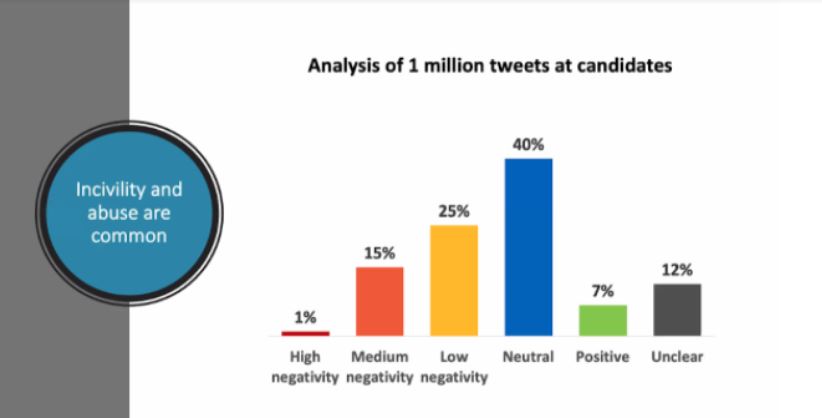

A report on online abuse in Canadian politics, led by researchers Chris Tenove and Heidi Twerek, suggests that about 40 per cent of tweets at candidates were uncivil, and 16 per cent of all tweets were abusive. Just seven per cent were positive.

The Twitter analysis covered over one million tweets at candidates and included interviews with over 30 candidates and campaign staff from the 2019 election along with 12 other elected officials.

According to the report, women and racialized candidates did not receive higher rates of abuse online “but the impact of the incivility and abuse they faced was often amplified by their lived experiences of threat, harassment, or marginalization offline.”

Iqra Khalid, a Member of Parliament, said, “One message that somebody had sent to me, and I will use blank instead of profanity, he said, ‘blank you softly with a chainsaw.’”

This is a message Khalid read out loud in Parliament when she tabled a motion to combat Islamophobia. She said it’s “amongst 10s of 1000s of messages” that she received.

“In 2017, a radio show or an IP TV show host had threatened to release my home address to people….It, you know, like, the fear is, is quite real. I mean, I don’t live alone. There are young kids in my home. You know, it’s, the fear is very, very real.”

Referencing the insurrection in the United States on Jan. 6, Khalid said, “ I think what has happened down south really helps us to understand what the severe implications of the ability for certain groups to organize on social media platforms [and] what that can lead to.”

Charlie Angus, a Member of Parliament, described how when an individual made attacks on Facebook that lasted every day for two months, police, at first, did not take them seriously. “I said ‘As a public figure, it’s one of the privileges of Parliament that I cannot be intimidated from my work. I have an obligation to serve the people and intimidation is a threat to the democratic rights not of me but of my constituents.’”

Tenove stressed, “[These messages] have a serious impact. And they do in part because they mirror or even amplify the forms of offline discrimination or threat that people face. And they add just another obstacle to running for office that are already faced by people from less well-represented groups.”

“This isn’t just a social media platform problem. Social media are often acting as a mirror…for sexism and racism in institutions, and more broadly in society. A range of organizations, including political parties play a role in contributing to the toxic discourse, and can do more to address it.”

A poll of 3,000 Canadians by Abacus Data suggests that 60 per cent of Canadians feel there needs to be government regulation of social media platforms. It was conducted for The Ryerson Leadership Lab in August 2019.

“[Online abuse is] making polarization worse. Incivility erodes our trust in one another and causes us to have greater dislike for people from other parties or other ideologies,” said Petit-Vouriot.

Recommendations to addressing the issue

The report, by the Centre for the Study of Democratic Institutions, University of British Columbia, suggests:

- Candidates and campaign teams should implement proactive plans to manage abuse and incivility and publicly communicate their expectations for people who engage them online.

- Political parties should provide training and resources on managing online abuse, provide support for candidates’ diverse experiences and risks and establish guidelines for online conduct.

- Social media platforms should develop clearer and more reliable enforcement of terms of service and improve their transparency about patterns of abuse and their activities to address it.

- Policymakers should clarify and improve the laws and police procedures for addressing online threats, defamation and hate speech.

“At the end of the day, we need to have that sense of a public conversation that is still possible that we can hear each other across. We don’t have to agree on each other’s politics. But there are elements in every political vision that adds to the whole of who we are as Canadian,” Angus said.

Reedah Hayder

Reedah Hayder is a journalist based in Toronto and a member of the NCM-CAJ Collective, actively reporting and managing social media. She is a second-generation immigrant and covers community, women's health, education and politics. She currently attends the Ryerson school of journalism and writes for The Eyeopener.