Hamid Karzai arrived in Kandahar 13 years ago, as a relatively unknown man ready to topple the Taliban’s stronghold and lead the country towards peace and democracy. As he steps down from his presidency and makes room for Afghanistan’s new president Ashraf Ghani Ahmadzai, many around the world are left pondering whether or not he accomplished what he originally set out to do.

At first, for many Afghans, Karzai appeared to be no different than the communist president Babrak Karmal who was once brought to power on a Russian tank with the help of former superpower, the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR).

But within no time, the citizens’ perception of him changed, and he became the most popular and beloved person in the country to many. Not only that, but when he came into office, he had lived in the U.S. making him the choice person amongst Americans to lead a country leaving behind over two decades of invasion and civil war. And of course, not to be forgotten, the Taliban movement had recently killed his father.

“His relatively successful transitional government and first term presidency had earned him popularity with the West, which later he began to lose after corruption allegation against his family and his lax stand against some of his corrupt cabinet members,” explains Mohammad Sediq, a recent Masters graduate from the University of Ottawa who explored e-governance in Afghanistan during his studies.

Despite his many deficiencies and shortcomings, it is fair to say Karzai made many strides during his tenure. He was the reason that once-rival Jihadi leaders, who fought each other during the 1990s, gathered around the same table to work for peace. Over seven million children, 40 per cent of them girls, go to school today while there were only one million male children who had access to a war-torn education infrastructure under the Taliban.

In a country where there were only 20,000 teachers, there are close to 200,000 teachers today, 30 per cent of them female, who teach in close to 5,000 schools. In a country where women were once no more than prisoners in their homes under the suffocating Taliban vice and virtue rules, they now have the opportunity to come out and become contributing members of Afghan society. Women are now members of parliament; they own their own businesses.

Thousands of miles of roads were built to connect the people in different parts of the country, both amongst each other and with the world beyond. There are 12 million people who own cellphones, compared to a time when people had to travel to a neighbouring country to make a phone call to a family member living outside Afghanistan. In a country where TV was once illegal to watch, there are now close to 100 private and state-owned channels, around 200 radio stations and 11 news agencies.

Karzai achieved all of this.

Despite his many deficiencies and shortcomings, it is fair to say Karzai made many strides during his tenure.

That being said, many problems persist. Complex issues such as insecurity and injustice have yet to be resolved. Human rights and women’s rights violation still howl in the country. Women are still raped and murdered. Child marriages haven’t stopped. The question of corruption lingers. Afghanistan is still the supplier of three folds of illegal drugs to the world (80 per cent of the global opium production, according to a UN Report). And addiction is a relatively new phenomenon following the return of Afghans who had fled to neighbouring Iran and Pakistan beginning in 2001.

The question remains: was Karzai part of the problem or the solution? In fairness, he did what he could accomplish as a fragile and inexperienced politician. At the time he was seen as a one-eyed-man among the blind. He was the only choice Afghans had after three long decades of crisis and sufferings. The alternative to him: warlords who once destroyed the capital and killed many civilians.

“If I had the experience I have now, I would have made different decisions in some cases, and I would have accomplished more than what I did within my 13 years as president,” Karzai said in a recent speech.

Some experts, like Sediq, disagree. “There would have been less problems if he hadn’t lost his grip over his leadership and dealt with the challenges like a good leader… To me, [his legacy is that of] a weak leader who wasted $120 billion of civilian aid, which would put an end point to any chaos in any country.”

How Things Went Sour

It all started in 2009 when Karzai won against Abdullah Abdullah. Karzai strongly believed that the Americans intervened in the election, because they did not want him to be the president any more.

When the Americans first descended upon Afghanistan, no one doubted the strong ties between Kabul and Washington. After suffering for two decades from misery and devastation, Afghans breathed a sigh of relief because of this friendship. American soldiers actually sat in restaurants and ate side by side with ordinary Afghans with no security concerns. The westerners, particularly the Americans, were seen as liberators of the nation. There are still many Afghans who honour the number of American lives lost in Afghanistan. There is a strong support among the public for the U.S.

But in one of his last speeches, President Karzai warned the incoming government to be particularly cautious in its relations with the United States and the western world. Although his remarks came as a surprise to members of both the Afghan and international community, the tension between Karzai and the U.S. is neither new or for one particular reason.

It all started in 2009 when Karzai won against Abdullah Abdullah. Karzai strongly believed that the Americans intervened in the election, because they did not want him to be the president any more.

In addition, the issue of civilian casualty rates played a role in tarnishing the relationship between Karzai and the U.S. When the Taliban regrouped across the border in the tribal area of Pakistan and was fighting fierce battles in the south against the International Security Assistance Forces (ISAF) many civilians were caught in the crossfire. Thus, Karzai was put in the hot seat. He received much public criticism and felt enormous pressure, particularly from the Pashtuns in the south. To make matters worse, the Taliban raised public sympathy by using the issue of civilian casualty in a sophisticated, yet effective, propaganda campaign to recruit new forces.

Karzai cried out for help from the Americans, who tried to address the issue, but failed time and time again. Karzai made these failures by the U.S. known widely, and by doing so, made the two countries’ relations even worse.

While Afghanistan may not practice the kind of democracy that exists in Canada right away, it doesn’t mean that the country has to move as slow as it did during the Karzai presidency.

Then came the Taliban negotiations, which both Washington and Kabul agreed to do. Unfortunately, the efforts weren’t unified and collaborative, which created a lot of distrust between the two governments. “Karzai called the Taliban – a fierce enemy of the U.S. allies – his brothers, and began to release them unconditionally from the prison without the U.S. consent. Some of [them] rejoined the fight against ISAF and the Afghan government,” said Sediq. This led the U.S. to rely more on cooperation from Pakistan than the Karzai government in its side of negotiations with the Taliban.

Sediq reasons that this was all part of a strategy at work. “[Karzai]’s popularity among the public had tremendously gone down because of corruption allegation against his family and some of his cabinet members [so] he cleverly started to shift the blame on the western allies particularly the U.S. He changed the perception of Afghans had about the U.S. from a savior of the country to a barbaric force that is there to kill innocent Afghans and destroy their country.”

The verbal clashes reached a boiling point. Karzai recently blamed the U.S. – once an ally in the war on terror – for fueling the conflict in Afghanistan. “If the U.S. honestly wants it, peace will come to Afghanistan the next day,” he said.

The Future: What’s Next For Afghanistan?

Despite the long wait and public critics of the recent Afghan election result, many Afghans see the new power-sharing government as the best option. President Ahmadzai’s speech at his inauguration was full of hope and promises to many Afghans and foreign allies. Amongst his promises: justice system reform and a new administration with half its members being young generation or women.

His newly appointed chief of security council signed the pending bilateral security agreement with the United States, allowing almost 10,000 U.S. troops to remain in the country and continue to educate Afghan security forces. Many believe Ahmadzai is a much stronger president than Karzai. “If he walks his talk, he will overcome the challenges he inherited from Karzai’s era,” says Sediq.

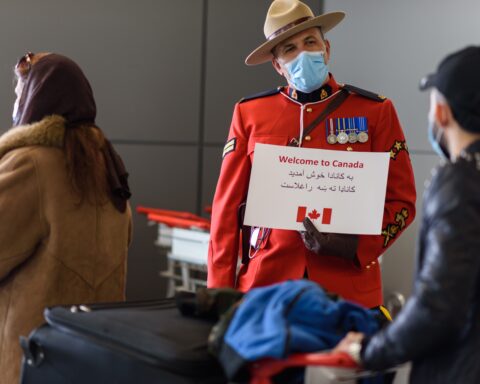

While Afghanistan may not practice the kind of democracy that exists in Canada right away, it doesn’t mean that the country has to move as slow as it did during the Karzai presidency. A traditional society like Afghanistan needs time to change and won’t tolerate too much change at once. In order for change to happen, the people need to be educated in order to shift the mentality in the society, and there needs to be unity amongst the different ethnic groups, long disconnected due to ongoing conflict.

As Toronto-based Afghan journalist Breshna Nazari points out, Afghanistan needs one thing above all: peace. Many Canadians, who have followed the war on terrorism from the other side of the globe, particularly families of the nearly 160 soldiers who have lost their lives in the war, would likely agree. “To obtain that goal the Taliban needs to lay its arms down and reconcile,” Nazari says. “I am not optimistic that people like General Dostum, Mohaqeq and even Dr. Abdullah who used to fight Taliban, and now are in the unity government, will allow such resolution to happen.”

Farouq Samim is an Ottawa-based communications consultant, with a Masters in Communication from the University of Ottawa where he studied the Afghan conflict. For eight years (2001 to 2009) he worked as a freelance producer, reporter and human rights investigator in Kabul, Afghanistan contributing to Aljazeera English TV, the Chicago Tribune Newspaper and Human Rights First.