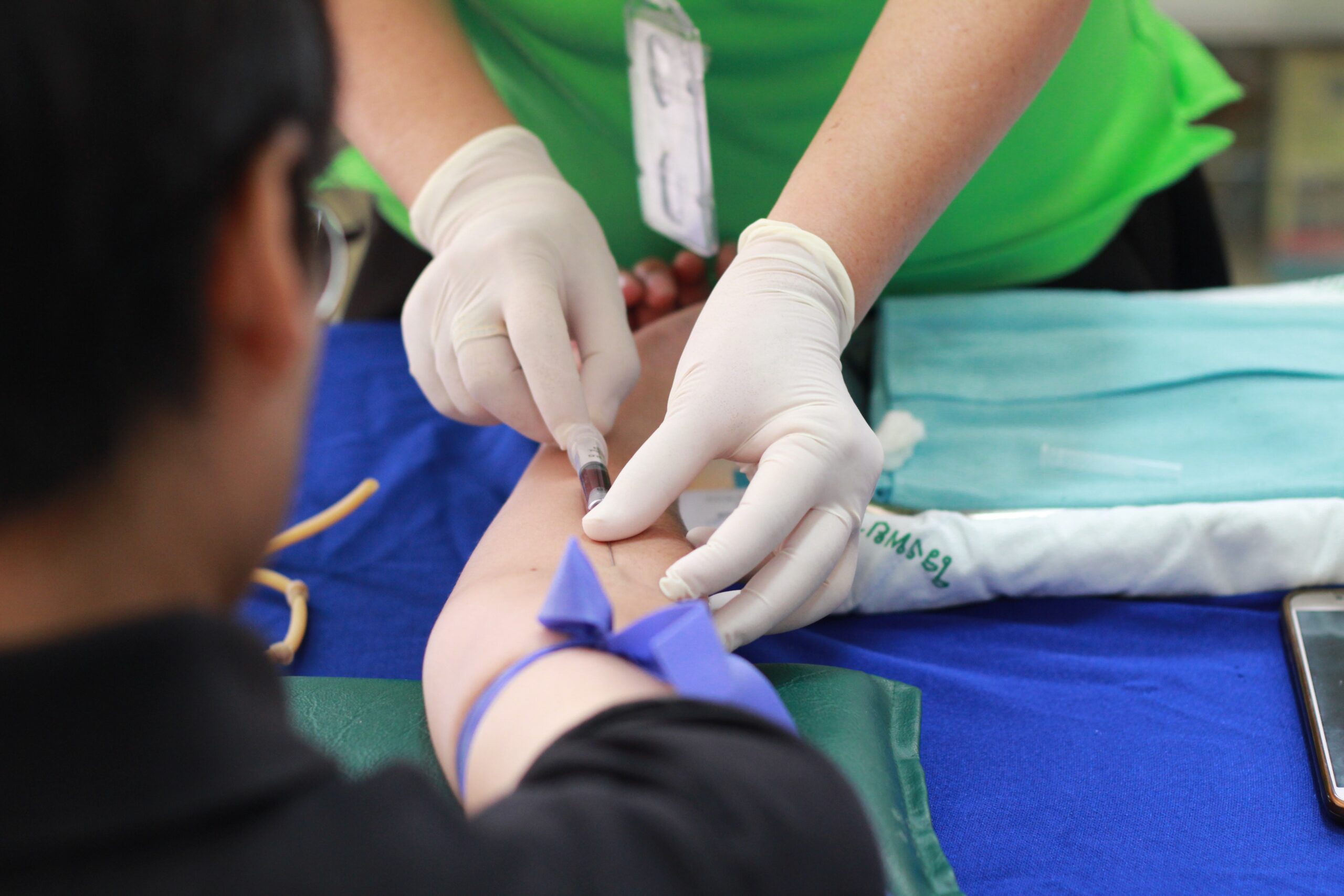

As Manitoba moves out of code red for the first time in seven months, the province’s hospitals are all breathing a collective sigh of relief. Between demanding 16-hour shifts, scarce critical supplies and the overwhelming number of patients requiring urgent care — a recurring issue that has gripped the nation over the past year — the pandemic has pushed an already dangerously strained system to the absolute brink.

“We have had many nurses who are putting their hands up and saying ‘I didn’t sign up for this.’ They are exhausted mentally, physically and psychologically.” Manitoba Nurses’ Union president Darlene Jackson told New Canadian Media.

“We don’t have a bleed of nurses out of the system. We have a hemorrhage.”

Nursing shortages in the province have reached an unprecedented all-time high during the pandemic. In January, the Winnipeg Regional Health Authority reported 1,283 empty nursing positions in Winnipeg, a vacancy rate of almost 17 per cent. In some areas, such as Manitoba’s Northern Health Region, the rate of unfilled nursing jobs is 47.4 per cent.

Nursing vacancies are a chronic issue that persisted prior to the pandemic, with former Health Minister Cameron Friesen previously stating that eight per cent was a ‘normal’ nurse vacancy rate back in 2019.

But a shortage of this scale has undeniable repercussions on the quality of care patients receive.

An intensive care unit (ICU) normally functions on a ratio of one nurse caring for one critically ill patient. According to Jackson, ICU nurses are currently compelled to care for three to five patients simultaneously. The situation is so dire that some severely ill Manitobans were transferred to hospitals in Ontario — not due to a lack of beds, but rather a lack of nurses.

Dan Buenaventura, a member of the Philippine Nurses Association of Manitoba, is all too familiar with the consequences of this shortage. While witnessing death is not an uncommon feature of being a nurse, he has never had to bear witness to so many patients dying alone.

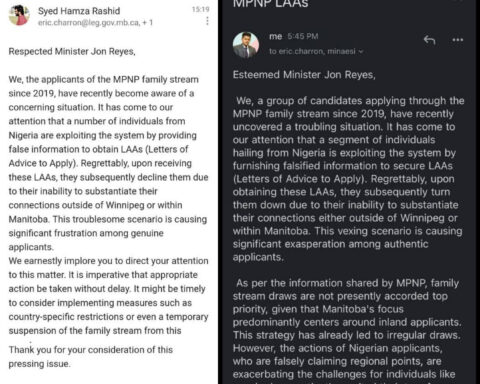

Buenaventura suggests that the challenges facing hospitals are “deeply rooted” in the staffing issues in the province — Manitoba nurses have been working without a contract from the provincial government since 2017 and some internationally educated nurses (IENs), who are eager to help shorthanded hospitals, have been forced to watch the pandemic ravage their communities from the sidelines due to red tape from regulatory bodies.

“Manitoba has lost a good number of nurses because of the strict registration process in the province,” Buenaventura said. “And these nurses are more than qualified to work. They have in fact been given good commendations by their peers, by their managers, and by the patients that they care for in other provinces or in the countries they worked in before they moved to Canada.”

Joyce, whose real name has been withheld due to fear of reprisal, is one of many Filipino internationally educated nurses who are unable to work in Manitoba due to licensing issues. Despite working as an ICU Registered Nurse (RN) in the Philippines for over six years, the College of Registered Nurses Manitoba (CRNM) advised Joyce to complete a four-year nursing program based on the results of her Clinical Competency Assessment (CCA), an examination administered by the CRNM that assesses nursing knowledge and practice.

Reluctant to return to school and anxious to make a living to support her family, Joyce made the tough decision to leave Manitoba and move to Newfoundland and Labrador in the middle of a pandemic, where she was authorized to work as an RN at the Centre of Nursing Studies in St. John’s. As her household also encompasses her 92 year-old grandmother, Joyce was forced to leave them behind for their safety.

Joyce had hoped that working in another province would allow her to eventually return to Manitoba and legally practice as an RN. The CRNM allows internationally educated nurses employed as RNs in other provinces to work in Manitoba provided they have practiced a minimum of 450 hours in the last two years. While Joyce met this requirement in March, the CRNM told her she could not transfer her licence from Newfoundland and Labrador to Manitoba as she’s ineligible based on the results of her CCA.

Instead, the CRNM gave her two options: pay $2,400 to take the CCA again, or take the four-year nursing program they initially suggested.

Joyce has yet to make her choice, but she does know that she’d prefer to work in Manitoba. “My family is here,” she said, “My grandmother is 92. Just in case something happens to her I’d like to be there so I could help.”

A few of these internationally educated nurses working as RNs in other provinces have years of experience in Manitoba’s hospitals. Albert, whose name has also been withheld, worked as a licensed practical nurse in Manitoba for almost five years. In 2020, his employer personally reached out to the CRNM to allow Albert to work as an RN in their hospital under a temporary licence. An RN licence for Albert would mean better wages (a minimum difference of $8 an hour) and is more in tune with the scope of his practice in the Philippines.

Unfortunately, the CRNM rejected Albert and his employer’s inquiry due to the fact that Albert had previously taken the CCA in 2013 and was advised to take a four-year nursing program. Unable to work as an RN in Manitoba, Albert relocated to southwestern Ontario, which quickly accepted him and allowed him to work in the province without any issue.

“I feel frustrated and heartbroken,” Albert said, “as the province that I have served for the longest time can’t back me up on this issue. They keep saying they need nurses, but they don’t give us a chance.”

According to the CRNM’s latest annual report, Filipino nurses represent the largest number of internationally educated nurses in Manitoba. Tapping into the significant pool of nurses who would like to join these ranks but are stuck on the outside looking in could alleviate some of the pressure on Manitoba’s fragile healthcare system.

Ron, a licensed practical nurse working in a designated COVID-19 unit in Manitoba, argues that more IENs should be given the chance to practice in the province.

“A shortage of RNs in Manitoba can put a licensed practical nurse in a role which is out of their job description,” Ron shared. “More licensed IENs will be a great advantage as more Manitobans receive the best and safest care possible.”

But the CRNM asserts that the requirements it requests from all nurses are crucial in assuring the public that nurses meet a certain standard of care. The CCA is an important part of assessing whether a nurse is fit to practice.

Katherine Stansfield, CEO & Registrar of the CRNM told New Canadian Media, “We want all internationally educated nurses to be employed to their fullest potential, but most importantly, we want them to be practicing safely.”

Applicants who were advised based on the results of their CCA that they lacked certain knowledge need to show the CRNM that those gaps have been filled.

“If you were able to somehow achieve registration in a different jurisdiction, and then you wanted to come back to Manitoba, we can’t just automatically assume that all those gaps have been addressed,” Stansfield said. “We know about them. It’s our obligation to the public to say, ‘Okay, how did you meet those gaps?’”

Ron argues that in light of the pandemic, the CRNM could use this opportunity to make their licensing process more flexible for IENs.

“I understand that the main requirement to become a nurse is the ability to provide safe practice for all patients,” he said, “but the competency of a nurse cannot be assessed through one four-day examination.”

Regardless of whether or not the requirements imposed by the CRNM are based on securing an ideal standard of care or a factor that increases the burden faced by Manitoba’s increasingly overworked healthcare staff, the three Manitobans removed from local hospitals and placed in the care of the Thunder Bay Regional Health Sciences Centre in Ontario will not have the freedom to utilize Manitoba’s healthcare system and recover near their loved ones. Instead, they will be cared for by nurses like Albert, who amply meet the qualifications to work as a nurse in Ontario. But it’s hard not to wonder whether some of these nurses, who are eager to return to their lives in Manitoba, are a missed opportunity for an alarmingly overburdened system on the verge of collapse.

“How is it possible for every healthcare facility in Manitoba to provide safe care if every day they’re always understaffed and our frontliners are overworked?” Albert said.

Reporting for this story was supported by the Pulitzer Center.

Alec Regino is a freelance journalist based in Vancouver, BC. He was a Reporting Fellow for the Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting in 2021.