Contemporary Japanese Canadian artists are using different forms of art to unearth and process their ancestors’ lived experiences through the Japanese Canadian internment, which displaced over 22,000 people of Japanese ancestry from British Columbia beginning in 1942.

The displacement included over 75 per cent of Canadian-born or naturalized citizens, many of whom were also dispossessed of their property. After a detainment period in a makeshift transit centre in Hastings Park Exhibition Grounds in Vancouver, most were sent to isolated internment camps in the interior of the province.

The detrimental impacts on the Japanese Canadian community included loss of livelihood, culture, and legacy. One of the most pervasive effects was also the silence that ensued among the community, which has affected future generations’ ability to learn about and connect to their culture.

The 2016 census reported 121,485 people of Japanese origin in Canada, 0.35 per cent of the Canadian population, most living in Ontario and B.C. Japanese Canadians were younger than Canadians as a whole, with approximately 38 per cent younger than 24 compared to 29 percent of Canadians.

“Unearthing the Past: Japanese Canadian Artists on the Legacy of Internment,” hosted by the Vancouver Public Library (VPL) on April 26, was meant to mark the internment’s 80th anniversary, exploring the ongoing repercussions of that communal silence and the ways these new generations have responded to it. Funded by Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada (IRCC), the event is part of VPL’s “Uplift Asian” series, which aims to celebrate Asian voices and counteract discrimination.

“There are deeply ingrained reasons why some Japanese Canadians don’t identify as Japanese Canadians,” says Jon Sasaki, a Toronto-based multidisciplinary artist. “And that in itself is an important part of the story.”

Grappling with identity

In 2012, Sasaki was invited to participate in the Nikkei National Museum’s 70th anniversary of the internment by showcasing his video about a man trying to reach the top of a wall without a tall enough ladder.

But he resisted, he says, because at the time, he couldn’t see the connection of his work to his Japanese heritage. However, despite his objections to not fitting into the theme, the curators included his video anyway — something for which he is now grateful.

“I now realize that my denial, or sort of obliviousness, to this Japanese Canadian identity didn’t come out of nowhere,” he says. “There were powerful historic forces that shaped this position.”

Being half Japanese, Brent Hirose, who describes himself as a “multipurpose theatre artist,” has also grappled with the question of “where you fit with your cultural identity” within theatre and film.

Meeting other Japanese Canadian artists with similar experiences after moving to Vancouver from Winnipeg in 2011 was an important milestone.

“[I saw] how everyone shares a lot of perhaps not touchstones to Japanese history, but certainly touchstones to this emptiness, this void where that culture and that history would have been,” he says.

Hirose points to the fact that Japanese Canadians are the most intermarried diaspora group in Canada as a reflection of the “deliberate dilution” of their culture and history over time.

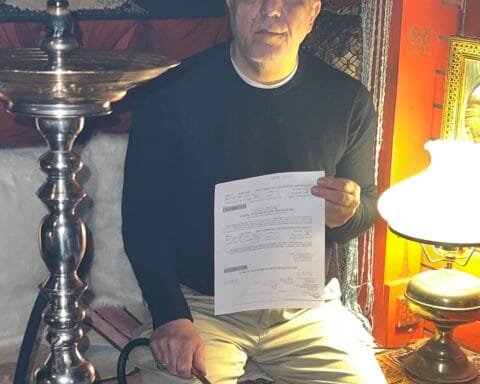

For Sasaki, when he finally delved into his family history, he found a document of the forced sale of his grandfather’s fishing boat. After being gifted a box of boat building tools by a family member, he created a performance around trying to build a boat to get out of the water without knowing how, representing that loss of generational knowledge.

Bringing history to life

The play “Japanese Problem,” which Hirose worked on with Yoshié Bancroft and Joanna Garfinkel, provided an immersive experience in the horse stables in Hastings Park. Hirose says that the profound impact of “the visceral realness of what happened” experienced by the audience, made it important to create time for post performance dialogues and a space to decompress.

“I think that this work is so important for us as Japanese Canadians, not only to tell our own story, but to be able to put a face to something that otherwise has been largely erased,” says Hirose.

“And [it] does not have the same [impact] as when you’re reading it through a textbook, as to see somebody living through [it] … to feel the connection.”

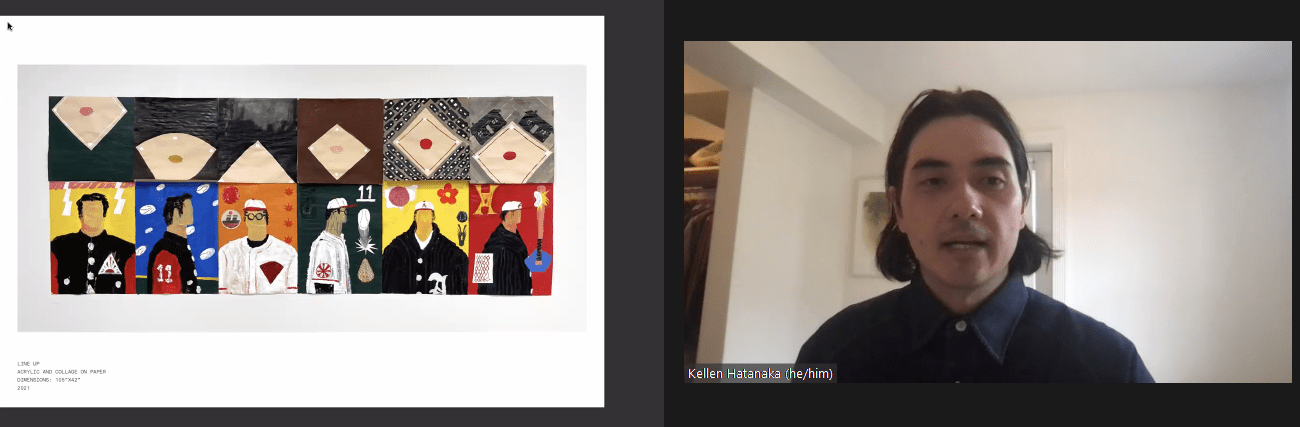

While doing research through the Landscapes of Injustice archive, Kellen Hatanaka also discovered that his grandfather and great grandfather had owned a grocery store in Vancouver that they were forced to sell and that his great grandfather on his grandmother’s side had passed away while being held at Hastings Park.

Learning these things caused “a visceral reaction,” says Hatanaka, that he hadn’t experienced in the little he’d learned from his grandmother or at school.

Hatanaka then began to see the potential of using his art showcasing the Vancouver Asahi baseball team as a way to speak about the effects of the internment on past, present and future generations of Japanese Canadians. His exhibit, SAFE | HOME, currently featured at the Nikkei National Museum, visually explores what might have been had the team continued.

Bridging across cultures

Sasaki eventually had the opportunity to visit Japan, where his father’s family had lived a century earlier, while participating in several artistic residencies.

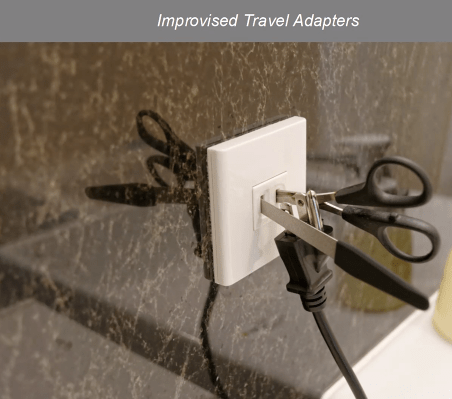

During his third residency at the Kosejii Buddhist Temple in 2018, he accepted that he “would forever be a fish out of water in Japan.” So when his three-prong American plug wouldn’t fit into the two-prong outlets without a portable travel adapter, he improvised.

“I was interested in finding ways to make these two culturally specific standards compatible,” says Sasaki. “And the subject, of course, is how we can adapt when we’re away from home, and how we can find ways of connecting and overcome these hurdles.”

During the Writing Wrongs project, showcasing letters written by Japanese Canadians to protest the confiscation and unconsented sale of their property, Hirose had the opportunity to read a letter by his great grandfather on the docks of Steveston, B.C., where Japanese fishermen had gathered prior to internment.

During one of the audience “talkbacks,” a woman shared that as a young child, her poor family had suddenly received a new house to live in – a house previously owned by Japanese Canadians.

“Starting that unpacking of how … that possession and redistribution of wealth affected families, both negatively, and in her case positively, it was really interesting and a healing experience to go through,” says Hirose.

Stoicism as resilience

In Hirose’s view, it’s important to include the complexities of the Japanese Canadian experience in any art produced, recognizing that “a lot of discussion and discomfort and healing and hurting” continues today.

The large-scale paper teapot Hatanaka created has become a symbol of how his grandmother dealt with her experience: the hard, strong ceramic exterior representing the stoic way she spoke about it, and the bit of steam emerging revealing the little she let them see up top while water boiled beneath the surface..

“I felt like I maybe needed to be angry for her when she took that kind of stance, but I’ve come to see that resilience and way of being able to move forward and still have this beautiful life,” says Hatanaka. “And I think now that instead of just being upset or angry, I can continue to do this work and keep her memory and her legacy alive in that way.”

Daniela Cohen is a freelance journalist and writer of South African origin currently based in Vancouver, B.C. Her work has been published in the Canadian Immigrant, The/La Source Newspaper, the African blog, ZEKE magazine, eJewish Philanthropy, and Living Hyphen. Daniela's particular areas of interest are migration, justice, equity, diversity and inclusion. She is also the co-founder of Identity Pages, a youth writing mentorship program.