Like the Southeast Asian island nation itself, Taiwan’s film industry is small, and often overshadowed by international competitors. Despite its size, the industry and some of its talented directors deserve international recognition, says Tom McSorley, executive director of the Canadian Film Institute (CFI).

“Taiwan’s remarkably accomplished and varied cinema, both in terms of its superb craft and its thematic explorations of contemporary issues in modern Taiwanese society, deserves to be better known around the world,” says McSorley.

It’s with this in mind that the CFI is partnering with the Taipei Economic and Cultural Office (TECO) in Ottawa, which functions as the de facto embassy of Taiwan, to raise the profile of the country’s film industry in Canada.

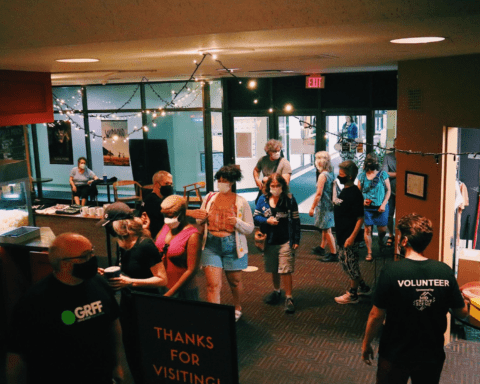

The two organizations introduced over 200 people, mainly of Taiwanese and Chinese heritage, to The Boar King at Carleton University’s River Building Theatre last week.

“Taiwan’s remarkably accomplished and varied cinema deserves to be better known around the world.”

With a strong local flavour and scenes shot in the southern mountains of Taiwan, as well as in the capital city Taipei, the film dramatizes a story of loss, courage, resilience and hope in the face of tragedy.

Universal themes

The Boar King’s themes are universal, and in some respects, strongly reminiscent of the American classic Gone with the Wind, in which the heroine Scarlett O’Hara struggles to cope with the upheaval of the civil war.

The central character, Cho, loses her husband, Ying, in a typhoon that left their village in ruins. The grief-stricken widow is dealing with the prospect of losing her family business, since a landslide has buried the source of water for her hotel spa in the village.

As her fellow villagers desperately try to sell off their land and move out, they receive mysterious invitation cards from her deceased husband.

What secrets is he hiding, Cho and her daughter Fen wonder, as they try to find answers through videotapes he had left behind. The journey points the way to a new path that helps them let go of the past and find a new direction in life.

The character of the grandfather who refuses to accept the fact that his property value has not diminished even after a landslide provides comic relief.

“Her message is that life will always remain uncertain, but once you have hope, you will have faith and confidence for the future.”

Unlike stories with a ‘and so they lived happily ever after’ ending, The Boar King concludes with Cho walking into a still uncertain future.

“This was deliberate,” Frank Lin, Taiwan’s acting representative in Ottawa, tells New Canadian Media. “Director Chen Ti Kuo is known for her documentaries and brings a strong note of realism even to her fictional movies. Her message is that life will always remain uncertain, but once you have hope, you will have faith and confidence for the future.”

High calibre of directing

In The Boar King the past is depicted in stunning coloured shots emerging from the video left behind by Cho’s husband, while the present scenes of destruction and desolation are portrayed in black and white scenes.

“This is a deliberate technique used by the director to emphasize the contrast between their past and present lives, and is not a problem with the equipment,” Lin said when introducing the film at the screening, drawing a laugh from the audience.

“Compared to the dream and memory sequences, the present seems harsh and bitter,” said Kuo, at an earlier screening in Montreal. “But when a brightly coloured butterfly flies and crosses over into the black and white reality, the boundary between the dream and reality is blurred and the woman starts to walk into the future.”

“A movie by Hou Hsiao-Hsien invariably features sparse dialogue, muted colors, passions held in check, and a deeply aesthetic feel.”

As McSorley points out there are many young and talented directors coming out of Taiwan, and Kuo appears to be one of them.

Her work follows in the steps of Taiwanese director Ang Lee, who was behind Life of Pii, the 2012 adventure drama starring Indian actors Suraj Sharma and Irrfan Khan, as well as director Hou Hsiao-Hsien who won the Best Director award at the 2015 Cannes Film Festivkal for The Assassin.

Lin illustrates this by referencing The Boar King’s sparse dialogue – in Taiwanese, with English and Mandarin Chinese subtitles – which is offset through the use of body language and facial expressions that portray a range of emotions from anger and despair to gradually emerging hope.

“A movie by Hou Hsiao-Hsien invariably features sparse dialogue, muted colors, passions held in check, and a deeply aesthetic feel,” says Lin.

What this film initiative, CFI and TECO aim to showcase that Taiwan dramas offer an alternative to the blockbuster movies of Hollywood and Bollywood that often produce purely escapist entertainment.

“Taiwanese directors turn normal, regular lives into art,” explains Lin. “It is the reason why we introduce Taiwanese films to our Canadian friends.”

Another Taiwanese film Hear Me will be screened at Carleton University’s River Building Theatre on Nov. 13 at 7 p.m. Admission is free.

Ottawa-based writer/journalist, editor, blogger, communications professional seeking freelance opportunities in political and travel writing.