The job of an academic is to be critical of government policy, not praise it, but in the case of Citizenship and Immigration Canada’s (CIC) new Express Entry (EE) system, there is much to like.

What I like best about the EE system is that it makes the objective of economic immigration explicit. The points in the Comprehensive Ranking System (CRS) used to select applicants in the EE pool are based (perhaps too loosely … but more on that below) on a statistical analysis of the factors that best predict post-migration labour market earnings.

For an economist, earnings first and foremost reflect worker productivity and the human capital that gives rise to that productivity. If the objective of economic immigration is to raise average productivity, and in turn average Canadian living standards, then selection policy should first and foremost target migrants whose expected earnings are above the current Canadian average.

“Cream skimming”? Perhaps.

One can, of course, argue that this economic focus is too narrow, but that’s why we have other immigration programs. I’m entirely sympathetic to the view that allocating 10 per cent of permanent residency (PR) slots to humanitarian immigration is not enough, but that’s a much bigger issue, and not a criticism of the EE system.

[A]ssuming that an open-door immigration policy is politically infeasible, and that the number of prospective immigrants exceeds available slots, the government must somehow discriminate between applicants. But how?

I have also heard EE criticized on the grounds that it’s “cream skimming,” catering exclusively to those with high economic value to Canada.

The challenge is, assuming that an open-door immigration policy is politically infeasible, and that the number of prospective immigrants exceeds available slots, the government must somehow discriminate between applicants. But how?

For economists, the most efficient way to allocate scarce resources is through prices. But, selling PR slots to the highest bidders is a bad idea for all kinds of reasons, not the least because worker productivity is imperfectly correlated with wealth.

An alternative approach is to do what universities do in selecting students: set an eligibility rule for application – a high school diploma, for example – and use a set of criteria to select among applicants. This is precisely what the EE system does.

The Federal Skilled Worker and Trades Programs and Canadian Experience Class define eligibility and the CRS points provide a mechanism to select individuals from the pool of applicants. Is this “cream skimming”? Perhaps. But what’s the alternative?

We could let eligible candidates wait in a queue for an indefinite duration until their turn comes up, as we used to do. But wouldn’t most applicants prefer a transparent system that allows them to improve their application in order to rise to the top? Would we prefer if universities admitted students in the order that their application was received?

Room for improvement

Room for improvement

Although there is much to like about EE, there are two features of the current CRS that concern me.

First, predicting the Canadian earnings of prospective immigrants is difficult.

A presentation at this year’s Metropolis Conference showed that, at best, the CRS predicts 10 per cent of all the variation in immigrants’ earnings 10 years after their arrival in Canada. Meaning, the order in which individuals are ranked in the EE pool looks very different from how they would be ranked if we knew what their actual earnings were 10 years after landing in Canada.

Of course, one can argue that selecting individuals on objective criteria, even if they are weak predictors of future success, is better than selecting randomly, but why not improve the CRS system by using better predictors?

For example, economists know that the best predictor of future earnings is past earnings. Why not exploit information on pre-migration earnings, by having applicants submit a recent income tax return from their origin country? Here is where engaging the research community could prove valuable for CIC, but doing so would also require making its Immigration Database (IMDB) accessible through Canada’s Research Data Centres.

Second, as my PhD supervisor once told me, if you’re going to let the data do the talking, you must tie your hands and not overlook inconvenient results.

The current CRS gives employers a central role in immigrant selection by putting a high value on job offers. In fact, a job offer (or Provincial Nominee Program recommendation) trumps any combination of human capital characteristics (except a perfect score).

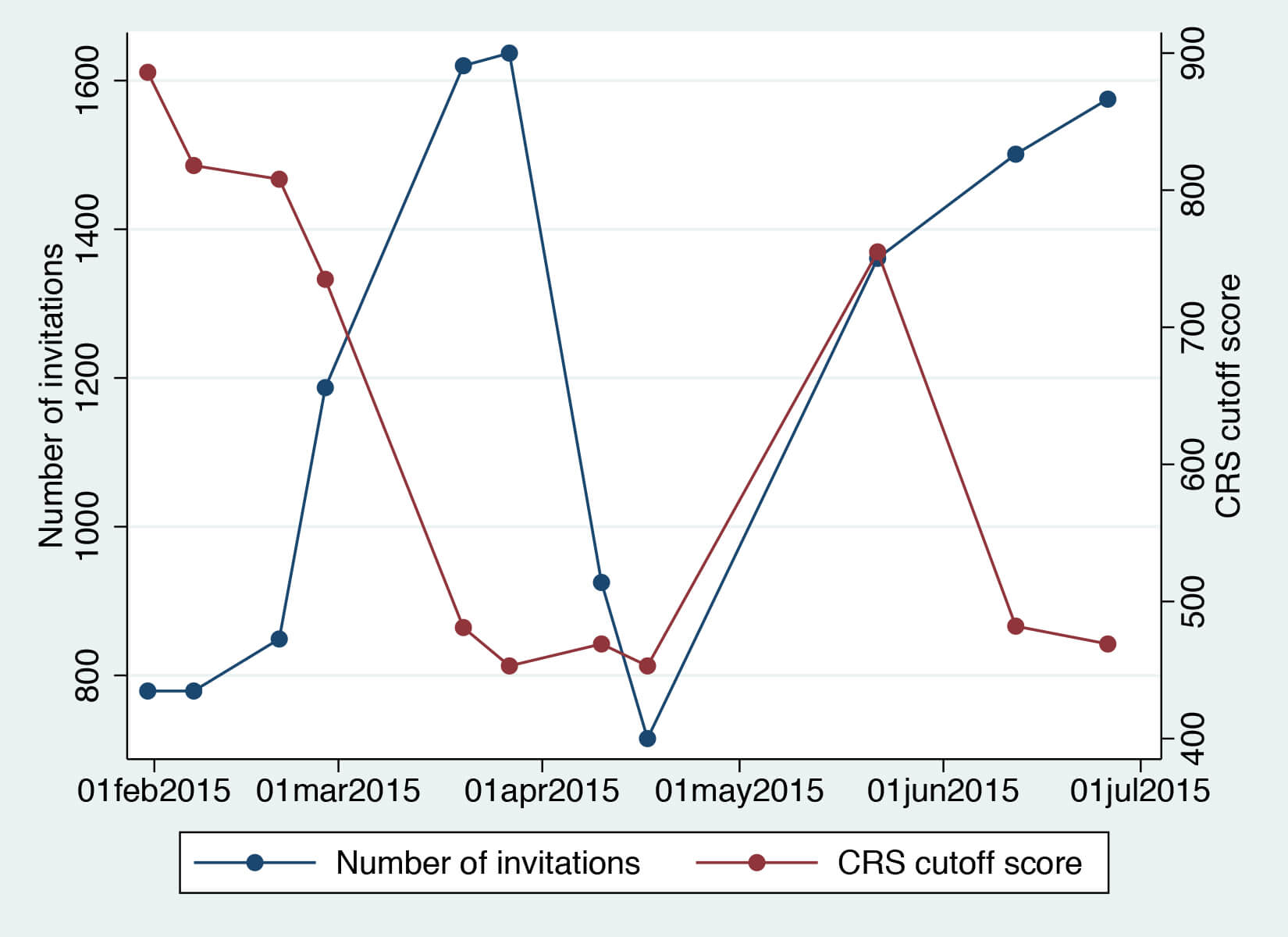

Although six of the first eleven rounds of EE invitations included applicants who did not have a job offer (or PNP recommendation), the minimum score cutoff to date is 453 (as seen in above graph). Note: a young newly minted PhD with impeccable English fluency wouldn’t reach this cutoff without at least some work experience.

Is this justified in terms of the ability of job offers to predict future earnings? The evidence suggests not. In a recent study published in Canadian Public Policy, economists Arthur Sweetman (McMaster University) and Casey Warman (Dalhousie University) find that, on average, skilled immigrants who have Canadian work experience prior to landing earn significantly more one year after landing, than those who don’t. However, this advantage falls by roughly one-half only three years later.

But perhaps job offers have little impact on who is ultimately selected, despite the extra points they provide? Again, the answer seems to be no.

Although six of the first eleven rounds of EE invitations included applicants who did not have a job offer (or PNP recommendation), the minimum score cutoff to date is 453 (as seen in above graph). Note: a young newly minted PhD with impeccable English fluency wouldn’t reach this cutoff without at least some work experience. This suggests that the vast majority of successful applicants to date have had a job offer or PNP recommendation (unfortunately, CIC doesn’t publish this information).

Work ahead for CIC

Are there risks in putting such a high value on job offers? The most concerning is that it creates incentives for corruption. An important task for CIC as the program is unrolled will be to monitor job tenure durations of folks who would not have cleared the CRS hurdle without an employment offer. There are, however, more subtle unintended consequences that CIC should be monitoring.

The reality for many immigrants is that clearing the CRS hurdle is impossible without a job offer.

First, the skills needs of the modern economy are more dynamic than ever. Skills that are in high demand today may be obsolete tomorrow. The large inflow of information and communications technology workers in the late 1990s and their subsequent labour market challenges following the Dot-Com crash of the early 2000s, provides an important lesson on the risks of putting too much emphasis on current labour market needs.

Second, with the increased cost of a Labour Market Impact Assessment – a tool used by employers to demonstrate the need to hire a foreign worker to fill a particular position – there is concern about the ability of foreigners, in particular international students, to compete for jobs.

This, however, assumes that employers must pay the LMIA cost. The reality for many immigrants is that clearing the CRS hurdle is impossible without a job offer. This can put a high value on a LMIA for prospective immigrants, far in excess of the $1000 processing fee that employers pay.

An important question for CIC is to what extent this value leads prospective immigrants to accept wage offers that they would otherwise not. Once again, closely monitoring the wage rates of not only immigrants who have cleared the CRS hurdle because of a job offer, but also the wages of Canadians who are competing with the same immigrants for jobs, will be important as CIC continues to phase in the new EE system.

Mikal Skuterud is an Associate Professor in the Department of Economics at the University of Waterloo and is affiliated with the Canadian Labour Market and Skills Researcher Network (CLSRN) and CERIS – The Ontario Metropolis Centre. He received his Master’s degree in Economics from the University of British Columbia and his Ph.D. in Economics from McMaster University. His research interests include: the labour market integration of immigrants and labour market policies that influence hours of work; and the labour supply adjustment behaviour of new parents. His work has appeared in the American Economic Review, the European Economic Review, the Canadian Journal of Economics, and the Journal of Labor Economics. His research has received national media coverage in the New York Times and the Globe and Mail.