“Almond,” “asthma,” “data” — growing up in a Bengali family in Mumbai, India, I was aware that some family members always pronounced those words exactly as they looked, articulating the “l” in “almond” and the “sth” in “asthma.” “Data” was the funniest. My dad and I always cracked up when he pronounced it daata instead of the North American day-ta because daata also happens to be the Bangla word for “drumstick,” a necessary ingredient in some of the most delicious curries known to humankind.

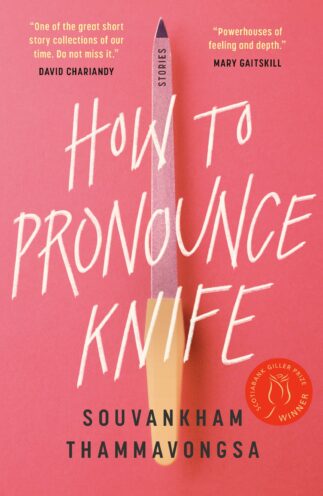

So, I couldn’t help smiling when I read the title story in Souvankham Thammavongsa’s prize-winning collection of short stories, How to Pronounce Knife. In that opening story, Joy, a Lao child who is learning to read, is told by her father that the word “knife” is pronounced kahneyff. Her classmates ridicule her, but Joy is insistent that her father is right: k in “knife” has to be pronounced.

“It’s in the front! The first one! It should have a sound!” she argues. In that moment, she takes a stand for her father, her family and, by extension, her culture and identity.

Thammavongsa herself is a child of Laotian immigrants. Each story in her collection offers the reader a glimpse into the day-to-day workings of immigrants and their families — their aspirations, their joys and their heartbreak.

But the author steers away from just talking about the immigrant struggle and the trauma of displacement, which is often a dominant narrative in stories about immigrants or by immigrant writers.

“A lot of things shape my writing. What I find interesting, what I get excited about, the details of what I observe, what I pick and choose to put on the page. Everyone has a childhood, a family — everyone grows up but that doesn’t mean they write about it,” she says.

Thammavongsa’s fiction has appeared in The New Yorker, Harper’s Magazine, Granta, The Atlantic, The Paris Review, Ploughshares, Best American Non-Required Reading, The Journey Prize Stories, and The O. Henry Prize Stories.

How to Pronounce Knife won the 2020 Scotiabank Giller Prize, finalist for the National Book Critics Circle Award and PEN/America Open Book Award. Recently the book was also named a finalist in the running for the 2021 Trillium Book Award. The title story was a finalist for the Commonwealth Short Story Prize.

Thammavongsa is also the author of four poetry books: Small Arguments (winner of the ReLit Award), Found, Light (winner of the Trillium Book Award for Poetry) and, most recently, Cluster. Born in the Lao refugee camp in Nong Khai, Thailand, she was raised and educated in Toronto, where she is currently working on her first novel.

The author spoke to New Canadian Media’s Baisakhi Roy via an email interview, excerpts of which we are publishing below:

The first thing that struck me about your writing was that it was devoid of embellishment and any kind of pretension. Could you tell us a bit about this choice of style of writing?

Souvankham Thammavongsa: I am so happy you feel this way about my writing. The kind of writing I do — this spare and plain language — withholds a great deal, and it can be frustrating for a reader because they have to do the work. When you read, you bring your whole life, your lived experience into the work you read, and if you have very little, then you might fault the writing for not giving you more. These stories are not sad stories, and this really becomes clear when I read them out loud, or when you listen to the audiobook.

The characters that stayed with me are the siblings and their father from “Chick-A-Chee!” A funny bit in the story is when the siblings are out at Halloween and they say “chick-a-chee!” instead of “trick-or-treat!” The couple in the posh house find this mispronunciation “adoooorable,” and the kids end up getting extra candy. Tell us a bit about the thought behind this story.

S.T.: Whenever we pronounce English words wrong, we are often expected to feel ashamed or embarrassed or humiliated — but that isn’t the right feeling. I didn’t feel that way, but I do see people expect me to. This story is about not belonging. It is about not wanting to fit in, about not being ashamed or embarrassed or humiliated. The question of the right way to pronounce “trick-or-treat” isn’t even an issue. It doesn’t matter how you say it because the candy is already in the bag.

Many of the stories in How to Pronounce Knife are told from the perspective of a child.Tell us a bit about what a child narrator brings to a story.

S.T.: There’s a difference between point of view and perspective. The stories in How to Pronounce Knife play with that difference. These are not children’s stories and they are not necessarily narrated by children. We learn, often in the end, that it is actually an adult narrating. As adults we never forget what we saw and felt as children, and even as adults we speak with the vocabulary of a child because that was the view and feeling we had when we first encountered the world.

What would you say is the recurrent theme in your collection and what would you want readers to take away from it?

S.T.: Laughter is the cornerstone of these stories. Laughter when we are the centre of it, or when we form it. I want readers to see themselves and to marvel at some of the sentences. I want them to cry, to feel heartbroken.

I want readers to see I don’t write from the margins and my characters are not in the margins. They don’t long to eat baloney or macaroni and cheese. They are not humiliated or embarrassed or ashamed. They don’t want to learn to speak English and fit in, they are proud of who they are where they come from. They aren’t nice and quiet and submissive.

There are sad moments, but that is not all that there is. I don’t pity anyone and I don’t try to convince anyone my characters are human or of their humanity. I assume it.

Immigrant stories tend to be largely about displacement and struggle, but so many of your stories could easily be about any family and the motions they go through, for example the funny yet poignant “Randy Travis” or the achingly beautiful “Slingshot.” Is there an effort in your writing to not stereotype the immigrant experience?

S.T.: I try to write a good book. That is where my effort is. There are stereotypes and bit characters that get placed in the margins, but they are not immigrants. We are not used to seeing that in literature, and that is a wonderful opportunity a good literary critic might give close attention to.

What did winning the Giller for How to Pronounce Knife mean to you?

S.T.: It brought my writing attention in a way talent alone and good and hard work for many years cannot do. I am happy to have it, and it has been life-changing, but I work really hard for it not to have too much meaning. I will write more books, and if my books don’t win a Giller, or if a jury does not name or choose me, that book will still be good.

Finally, could you tell us a bit about what you are working on now and what can readers expect?

S.T.: I don’t think readers should expect things from me. It’s not fair and awful to the making of any art. I should be allowed to do whatever I want, including fail and disappoint and change readers.

Baisakhi Roy is a writer and journalist based in Oakville. Her work has been published in several Canadian media outlets includingThe Globe and Mail,Huffington Post Canada,Chatelaine,Broadviewand CBC. Her areas of interest and expertise lie in the intersections of immigrant life and culture in Canada. She is an avid Bollywood fan and co-hosts the Hindi language podcast KhabardaarPodcast.com.